Closing the Ring (29 page)

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

Tags: #Great Britain, #Western, #British, #Europe, #History, #Military, #Non-Fiction, #Political Science, #War, #World War II

12

Island Prizes Lost

Rhodes and Leros

Rhodes, Key of the Eastern Mediterranean___General Wilson’s Plans___Seizure of Rhodes, Leros, and Cos Approved by the Combined Chiefs of Staff, September

10___

The German Grip on Rhodes___Hitler’s Concern About the Aegean___The Germans Retake Cos___Imperative Need to Attack Rhodes___My Telegram to President Roosevelt of October

7___

His Disappointing Reply___My Further Appeal, October

8___

Washington Obdurate___My Wish to Attend Conference at Algiers Denied___News of Hitler’s Decision to Fight South of Rome___Wilson’s Report of October

10___

I Submit with Grief___The Fate of Our Leros Garrison___The Germans Attack, November

12___

A Bitter Blow.

T

HE SURRENDER OF

I

TALY

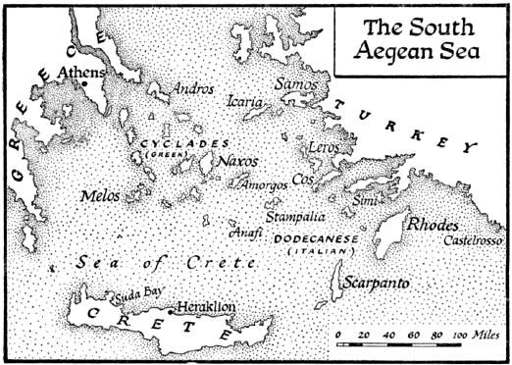

gave us the chance of gaining important prizes in the Aegean at very small cost and effort. The Italian garrisons obeyed the orders of the King and Marshal Badoglio, and would come over to our side if we could reach them before they were overawed and disarmed by the Germans in the islands. These were much inferior in numbers, but it is probable that for some time past they had been suspicious of their allies’ fidelity and had their plans laid. Rhodes, Leros, and Cos were island fortresses which had long been for us strategic objectives of a high order in the secondary sphere. Rhodes was the key to the group, because it had good airfields from which our own air forces could operate in defence of any other islands we might occupy and complete our naval control of these waters. Moreover, the British air forces in Egypt and Cyrenaica could defend Egypt just as well, or even better, if some of them moved forward to Rhodes. It seemed to me a rebuff of fortune not to pick up these treasures. The command of the Aegean by air and by sea was within our reach. The effect of this might be decisive upon Turkey, at that time deeply moved by the Italian collapse. If we could use the Aegean and the Dardanelles, the naval short-cut to Russia was established. There would be no more need for the perilous and costly Arctic convoys, or the long and wearisome supply line through the Persian Gulf.

I felt from the beginning we must be ready to take advantage of any Italian landslide or German round-up.

Prime Minister to General Ismay, for C.O.S. Committee

2 Aug. 43

Here is a business of great consequence, to be thrust forward by every means. Should the Italian troops in Crete and Rhodes resist the Germans and a deadlock ensue, we must help the Italians at the earliest moment, engaging thereby also the support of the populations.

2. The Middle East should be informed today that all supplies to Turkey may be stopped for the emergency, and that they should prepare expeditionary forces, not necessarily in divisional formations, to profit by the chances that may offer.

3. This is no time for conventional establishments, but rather for using whatever fighting elements there are. Can anything be done to find at least a modicum of assault shipping without compromising the main operation against Italy? It does not follow that troops can only be landed from armoured landing-craft. Provided they are to be helped by friends on shore, a different situation arises. Surely caiques and ships’ boats can be used between ship and shore?

I hope the Staffs will be able to stimulate action, which may gain immense prizes at little cost, though not at little risk.

Plans and preparations for the capture of Rhodes had been perfected in the Middle East Command over several months. In August, the 8th Indian Division had been trained and rehearsed in the operation, and was made ready to sail on September 1. But on August 26, in pursuance of a minor decision at the Washington Conference in the previous May, the Command received the orders of the Combined Chiefs of Staff to dispatch to India, for an operation against the coast of Burma, the shipping that could have taken the 8th Indian Division to Rhodes. The division itself was put under orders to join the Allied forces in the Central Mediterranean.

* * * * *

When the tremendous events of the Italian surrender occurred, my mind turned to the Aegean islands, so long the object of strategic desire. On September 9, I had cabled from Washington to General Wilson, Commander-in-Chief of the Middle East, “This is the time to play high. Improvise and dare.” General Wilson was eager for swift action, but his command had been stripped. He had only available the 234th Brigade, formerly part of the hard-tried garrison of Malta, and no shipping other than what could be scraped up from local

resources. The trained assault shipping recently taken from him was not beyond superior control, but the American pressure to disperse our shipping from the Mediterranean, either westward for the preparations for a still remote “Overlord” or to the Indian theatre, was very strong. Agreements made before the Italian collapse and appropriate to a totally different situation were rigorously invoked, at least at the secondary level. Thus Wilson’s well-conceived plans for rapid action in the Dodecanese were harshly upset. Thereafter we were condemned to try our best with insufficient forces to occupy and hold islands of invaluable strategic and political importance.

The “Long-Range Desert Group,” composed of soldiers of the highest quality, had been transformed into an amphibious unit, intending to reproduce on the sea the fame they had won in the sand. On the night of September 9, Major Lord Jellicoe, son of the Admiral, who was a leading figure in this daring unit, landed by parachute in Rhodes with a small mission to try to procure the surrender of the island. If we could gain a port and an airfield, the quick dispatch of a handful of British troops might encourage the Italians to dominate the Germans, whom they far outnumbered. But the Germans were stubborn and stiff, and the Italians yielded themselves to their authority. Jellicoe and his mission had to leave hurriedly. Thereafter the capture of Rhodes, held by six thousand Germans, required forces greater than were available to the Middle East Command.

The occupation of Rhodes, Leros, and Cos was specifically approved by the Combined Chiefs of Staff in their final summary of the Quebec decisions on September 10.

1

Wilson had sent with great promptitude small parties by sea and air to a number of other islands, and on September 14 reported as follows.

General Maitland Wilson to C.I.G.S.

14 Sept. 43

Situation in Rhodes deteriorated too rapidly for us to take action. Italians surrendered town and harbour (to the Germans)

after light bombing. Only an assault landing was thereafter practicable, but unfortunately 8th Indian Division, which had been trained and rehearsed for this operation, is now diverted to the Central Mediterranean and its ships and craft are dispersed by order of the Admiralty. Italian morale in Rhodes is below zero, and indicates little intention of ever resisting Germans in spite of asseverations to the contrary. We have occupied Castelrosso island, and have missions in Cos, Leros, and Samos. A flight of Spitfires will be established in Cos today, and an infantry garrison tonight by parachute. An infantry detachment is also proceeding to Leros. Thereafter I propose to carry out piratical war on enemy communications in the Aegean and to occupy Greek islands with Hellenic forces as opportunity offers. Since the New Zealand Division is also to proceed to Central Mediterranean, the 10th Indian Division, partially equipped, is the only formation immediately available.

As all Middle East resources have been put at disposal of General Eisenhower, we have no means of mounting an assault landing on Rhodes, but I hope to reduce the island by the methods adopted by the Turks in 1522, though in less time.

Once Rhodes was denied to us, our gains throughout the Aegean became precarious. Only a powerful use of air forces could give us what we needed. It would have taken very little of their time had there been accord. General Eisenhower and his Staff seemed unaware of what lay at our finger-tips, although we had voluntarily placed all our considerable resources entirely in their hands.

We now know how deeply the Germans were alarmed at the deadly threat which they expected us to develop on their southeastern flank. At a conference at the Fuehrer’s Headquarters on September 25, both the Army and the Navy representatives strongly urged the evacuation of Crete and other islands in the Aegean while there was still time. They pointed out that these advanced bases had been seized for offensive operations in the Eastern Mediterranean, but that now the situation was entirely changed. They stressed the need to avoid the loss of troops and material which would be of decisive importance for the defence of the Continent. Hitler overruled

them. He insisted that he could not order evacuation, particularly of Crete and the Dodecanese, because of the political repercussions which would follow. He said, “The attitude of our allies in the southeast and Turkey’s attitude is determined solely by their confidence in our strength. Abandonment of the islands would create a most unfavourable impression.” In this decision to fight for the Aegean islands he was justified by events. He gained large profits in a subsidiary theate at small cost to the main strategic position. In the Balkans he was wrong. In the Aegean he was right.

* * * * *

We rightly made no attempt to occupy Crete, where the considerable German garrison rapidly disarmed the Italians and took charge, but for a time our affairs prospered in the outlying small islands. Troop movements by sea and air began on September 15. The Royal Navy lent a helping hand with destroyers and submarines. For the rest, small coasting vessels, sailing ships, launches, were all pressed into service, and by the end of the month Cos, Leros, and Samos were occupied by a battalion each, and small parties were landed on a number of other islands. Italian garrisons, where encountered, were friendly enough, but their vaunted coast and anti-aircraft defences were found to be in poor shape, and the transport of our own heavier weapons and vehicles was hardly possible with the shipping at our disposal.

Apart from Rhodes, the island of Cos was strategically the most important. This alone had an airfield from which our fighter aircraft could operate. It was rapidly brought into use and twenty-four Bofors guns landed for its defence. Naturally it became the objective of the first enemy counter-attack, and from September 18 onward the target of increasing air raids. Our reconnaissance reported an enemy convoy approaching, and at dawn on October 3, German parachutists descended on the central airfield and overwhelmed the solitary company defending it. The rest of the battalion, in the north of the island, where the enemy landed, was cut off. Clearly a single battalion

—all we could spare—could do little on an island thirty miles long to ward off such a double blow. The island fell. The Navy had done their best, without success, to intercept the convoy on its way to Cos, but owing to an unlucky event all but three destroyers had been for the moment drawn away. As part of the main naval concentration at Malta, which was not especially urgent, two of our battleships had been ordered thither at this moment, and needed all the remainder to escort them.

* * * * *

On September 22, Wilson reported his minimum and modest needs for an attack on Rhodes about October 20. Using the 10th Indian Division and part of an armoured brigade, he required only naval escorts and bombarding forces, three L.S.T.s, a few M.T. ships, a hospital ship, and enough transport aircraft to lift one parachute battalion. I was greatly troubled at our inability to support the Aegean operations, and on September 25, I cabled to General Eisenhower:

Prime Minister to General Eisenhower

25 Sept. 43

You will have seen the telegrams from the Commander-in-Chief Middle East about Rhodes. Rhodes is the key both to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Aegean. It will be a great disaster if the Germans are able to consolidate there. The requirements which the Middle East ask for are small. I should be most grateful if you would let me know how the matter stands. I have not yet raised it with Washington.

2

The small aids needed seemed very little to ask from our American friends in order to gain the prize of Rhodes and thus retain Leros and retake Cos. The concessions which they had made to my unceasing pressure during the last three months had been rewarded by astounding success. Surely I was entitled to the very small aid which I required to supplement the British forces which were available for action in the Aegean, or had, with the approval of the Combined Chiefs of Staff, already been sent to dangerous positions. The landing-craft

for a single division, a few days’ assistance from the main Allied Air Force, and Rhodes would be ours. The Germans, who had now regripped the situation, had moved many of their planes to the Aegean to frustrate the very purpose which I had in mind.