Blow Out the Moon (12 page)

This is what I mean by the back of the fork.

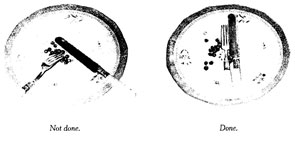

When you’re finished, put your knife and fork together in the middle of the plate, with the fork’s prongs facing up. When you’re not finished, put the handle of the knife on the right side of the plate, with the blade in the middle, and the fork handle on the left side of the plate, with the prongs in the middle and facing down. This is so the servants know when to take your plate away and when not to.

There are rules not just for how you eat, but what you talk about at meals.

One day my milk had yellowy splotches floating in it.

“Yuck!” I said. Matron looked cross. “Yuck!” wasn’t an English word, I knew that, but I was so surprised by the milk that it slipped out. I held out my cup: “Look!”

She looked.

“You’re jolly lucky — you got the cream!”

She frowned at me — then she frowned at Brioney and some other people, who were giggling. They stopped.

I took a sip before she could tell me to, but I could feel the lumps in it, and I made a face.

Matron looked even more annoyed.

There was a little pause and then she said, in her storytelling voice, “Once, there was a very important person.”

Everyone put down their knives and forks (in the still-eating position) to listen — we loved it when Matron told stories.

“This very important person went to a luncheon party, and there was a caterpillar in his salad. So he folded it up in a piece of lettuce —,” she imitated him putting the caterpillar in the middle of the lettuce, folding the lettuce neatly around it with his knife, and then pushing it firmly onto his fork, “— and ate it.”

She imitated him chewing and swallowing politely, with no expression at all on his face.

The others were listening calmly; I was horrified.

“But WHY?” I said. “Why would he do that?”

I looked around — Clare was looking amused; she didn’t laugh or smile, but I could tell something was making her laugh inside (you can tell by her eyes, and the corners of her mouth — they quiver a little). Matron looked at me and blinked in that mild, calm English way (it’s how they show that they’re surprised).

“He had to. He was a very important person.”

The others nodded and went on eating, as though that made sense. It didn’t to me. But I did understand that you don’t make comments (or even a face) about food, no matter what. So that night, when we had the English idea of spaghetti — plates of plain spaghetti, which they called “macaroni,” and a small pitcher of completely smooth, very runny ketchup to pour on top — I didn’t say anything.

Lessons

But I did still talk like myself during lessons.

Lessons started after quite a lot of others things had happened: When the bell first rang, we got up, dressed quickly, folded our mattresses in half (this was supposed to air them out), and went down to breakfast. Then we came back upstairs, made our beds, and lined up for prayers.

We marched through Marza’s part of the house to a beautiful room called the Long Room. It had big fireplaces at both ends and dark wood square panels on all the walls. We stood in rows. Marza stood in front of us, next to a very polished little table, and the mistresses all stood on one side.

We bowed our heads and said a prayer, and then, when Marza picked up her hymn book, we opened ours. (The hymn number for the day was always written on a little board in our part of the house, where we lined up.)

Then Miss Day played the piano and we all sang. That morning it was one of our favorites, “Onward Christian Soldiers.” We almost shouted the chorus:

Onward Christian SOLDiers!

Marching as to WAR!

With the cross of JEsus

Going on before!

I liked singing that.

The music to “Onward Christian Soldiers.”

After the hymn, Marza made announcements, if there were any. Announcements were usually just which dorms had been talking after Lights Out and how they would be punished. But that morning she said that seniors could audition for the school play that day after lessons.

Then, slowly and majestically, she picked up her prayer book and hymn book and walked out, her back very straight. Then (this happened every day), Miss Day played “The British Grenadiers” and we marched out, row by row, and went to our form rooms for lessons.

Our form, IIB, was in a long, low, white metal building by itself. There were windows all along one side of it and all day sun poured in — sometimes, it even got hot.

Everyone in the class was younger than I was. They were all-day girls (girls who didn’t sleep at the school but just came for lessons) except for Brioney and me and the only boy in the school, Mo.

Lessons were interesting — not at all like school in America. We read real books and copied

Alice in Wonderland

to practice our handwriting, and out loud we read real poetry. We had English History, World History, and Ancient History. In Nature Study we found plants in the woods and fields and drew pictures of them. In Geography we copied maps and colored in the sea with short strokes of light blue pencils. For Singing we went to a special room and Miss Barton played the piano while we sang old folk songs like “My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean” (after the first letter from Henry came, everyone thought it was hilarious to sing “My

Henry

lies over the ocean,” nudging each other and looking at me) and “Loch Lomond.”

I tried hard to be good at everything except singing: I have a terrible voice and I know it. (On my reports I always got “Poor.” Once she added: “Shows some improvement, though.”) French was hard, because I’d never had it. All the other kids had; and it was because I didn’t know it that I was in IIB, not IIA with Clare and the other girls my age. So I tried extra hard at French.

That day, while everyone was coming in and getting settled, I said eagerly, “Who’s going to be the star of the play?”

Miss Davenport gave me a scornful look.

“This isn’t a Hollywood production, Libby,” she said. “There is no

star

.”

Then she told us what chapter to read. The first lesson each day was Scripture. We always read the chapter, then closed our Bibles and wrote down everything we could remember; she corrected our Scripture while we did our arithmetic.

Next, we had Composition, and that day she told us to write about something interesting that had happened over the holidays. I know that you’re not supposed to complain and that no one in England does — I hadn’t the night before about the spaghetti — but sometimes I just can’t help it. I HATE writing about stupid subjects and I said so.

After a while, Miss Davenport said, “That will do, Libby,” and told us to begin.

Everyone else started writing and I just sat there, glaring out the window. Miss Davenport ignored me. Finally, when there were only a few minutes left, I thought of the train trip to the school. I’d spent part of it standing outside the compartment, looking out the window until a man started talking to me. I decided to write about our conversation.

When she’d read all the compositions, Miss Davenport said mine was “hilarious — I laughed and laughed” (she had, I’d seen her), and then she said she would read it out loud to everyone else.

“Libby, you may stand outside while I read it.”

I would have liked to stay and see what everyone thought (I’d be able to tell by their faces), but English people never act proud of what they’ve done; they always look embarrassed when people praise them. So I went outside.

Later, when we were playing by ourselves (we were allowed to play outside after lessons, and the two of us had climbed a tree), I asked Brioney what she thought of my composition. She said, “I didn’t see what was so funny about it, except when you called the corridor ‘the hall.’ ”

I hadn’t meant it to be funny, so that was kind of a relief. Then we started talking about something else, and Clare and Mo climbed into the tree with us and we were all talking and playing when some seniors came by and somehow — I forget whose idea it was — we decided to have a competition to see who could hang from a branch the longest.

Clare, Mo, Brioney, and I were the competitors; Retina (Brioney’s older sister) and Carol (Clare’s older sister) and some other seniors were the audience. The rules were simple: Hang from the branch with just your hands. The branch was higher than any of us could reach from the ground, so we climbed out to it; the seniors (who were a lot taller than we were — they all always seemed huge to me) said they would lift us down when we were tired.

“Just say,” Carol said, “and one of us will lift you down.”

We grasped the branch with our hands (I clasped my fingers together; I couldn’t see how the others were doing it) and dropped. It was a funny feeling, to be hanging from a branch with your feet high above the ground.

The seniors leaned against the fence to watch; Catherine Marshall was there and I think she wanted me to win. I wanted to win, too, of course; in fact, I REALLY wanted to. I thought I probably would: I was still very strong, probably stronger than any of them.

But after a while, my hands got a little sweaty and they started to slide apart. Clare and Brioney had already been lifted down: It was just Mo and me. I thought I could hang on if I just gripped tighter: My muscles weren’t tired at all. Suddenly — before I could say anything at all — my hands slid completely apart and I fell.

Mo, Brioney, and Tuppence

I landed right on my face. My tooth went through the skin just under my lip — I could feel the tooth do that, and blood trickling down, but the worst part was that I couldn’t breathe at first. It’s a sickening feeling: Has it ever happened to you? You can’t breathe — it’s as though there isn’t any air in your lungs.

“Brioney, get Matron,” Retina said.

As soon as I could talk, I said, “I’m okay,” and sat up.

“Better not move until Matron has a look at you,” Catherine Marshall said, but just as she said that, Matron came running up.

“I’m okay,” I said again.

When we were walking back to the house by ourselves, I told her about not being able to breathe and how much it had scared me.

“You had the wind knocked out of you, that’s all,” she said in a definite, very reassuring voice. “Still, I think you’d better have the doctor about that lip.”

The doctor came and stitched it up (he said I would have a little scar but because it was just under the lip it wouldn’t show much), and to stay in bed for two days.

Being sick at Sibton Park was kind of fun: Matron put a big jug of lemonade next to my bed, so I could have a drink whenever I wanted to, and whenever she had time, she came in and read to me or told me stories. Sometimes she asked me to read her

my

stories, and I did. Sometimes she brought her sewing in and we just talked, and I liked that best of all.

While I was in bed by myself, I thought about the children at Sibton Park. I thought that they all looked very English and that I didn’t, because of my slanted eyes — their eyes were so round. A lot of them had turned-up noses, and I wished I did, too.

Mo looked different from everyone else, too. It wasn’t just that he was the only boy: He came from Persia. He always wore gray shorts, gray socks, a white shirt with a tie, and a gray pullover with a V-neck. He had a serious little face with a big, big nose and round dark eyes that often had a worried expression. He was the shortest boarder and I was the second shortest. The only people who ever played with him were Brioney and I.