Blow Out the Moon (11 page)

As soon as I was by myself and could, I thought, do what I wanted (which was after I’d been moved into my new dormitory, the Night Nursery, and been shown around the school), I ran to the big meadow where the horses were.

I was a little surprised by how BIG they were and decided not to get too close. There was a dead tree, gray and smooth like driftwood, lying on its side in the sun, and I stood near that, watching the horses eating grass. After a while a big gray one lifted its head up and looked at me.

A pony in the big meadow. I took this picture myself, with a Brownie camera my father had given me.

It walked towards me slowly, kind of curiously, with its neck stretched out, swishing its tail. It looked very relaxed. It came right up to me and sniffed me. Then it touched me — sort of nudged me — with its nose. I didn’t know what to do. In books they always said horses could tell if you were scared, and that quick movements frightened them, so I just stood very still and tried not to be afraid. The horse bent down its head and shoved me with its nose until I was pushed back against the dead tree, and it was standing right in front of me. This wasn’t done in a MEAN way — it was as though the horse was old and bossy, and saying, “Get over there.”

So I did.

Then I was trapped between the horse and the tree. The horse’s neck was higher than my head. I stood still and started talking to the horse in a quiet, steady voice, the way people did in books. The horse pushed its nose against my chest — hard — so my back pressed into the tree, and then, very slowly, it rubbed its whole face against me, pushing hard, rubbing up and down my chest and stomach. It closed its eyes and rubbed the space in between them, and then the long bony part of its face that went from between its eyes down to its nose — over and over, up and down my body — and then it turned its head and put one foot out in front of the others (even its feet were big) and rubbed one side of its face against me, then the other.

It didn’t hurt, except where a bump on the tree was pressing into my back. I kept talking, quietly and calmly. Finally the horse kind of shook itself all over (as though it was saying, “Oh! I needed that!”); gave me one last nudge with its nose; and ambled away, head hanging down, neck stretched out, tail swishing. It stopped a few feet away from me and started munching grass again.

That was the first time I ever talked to a horse.

I felt a little proud of myself and very happy. I had talked to a real horse. The books had been right (I like it when things in books turn out to be true) — I’d remembered what they said to do and I’d done it.

When something frightening happens, the best thing to do, I think, is to stay calm, figure out what to do, and then (even if you’re afraid) make yourself do it, no matter what. “Make sure you’re right, then go ahead,” as Davy Crockett said.

Anyway, although it was a little scary at first, it was neat to have been that close to a real horse.

I walked back to the house slowly, out of the meadow and into “the paddock” and up some brick steps. Then I was on a big smooth lawn called the Lower Garden, with bushes cut into fancy shapes. The part of the house I could see from here (the house was huge, with more than a hundred rooms) was made of rose-colored brick; it even looked old. (I knew from the little booklet that it had been built in 1300-something.)

The paddock steps, with the Lower Garden and part of the house in the background.

And what I could see was only part of Sibton Park — there was another huge lawn called the Upper Garden, a Tudor Garden (twisty little brick paths arranged in a complicated pattern around little hedges, with an old sundial in the middle), tennis courts, and the Rose Garden. Our whole yard in America could have fit into half the Rose Garden. It was strange to think that one person owned all of it, that it used to be her house.

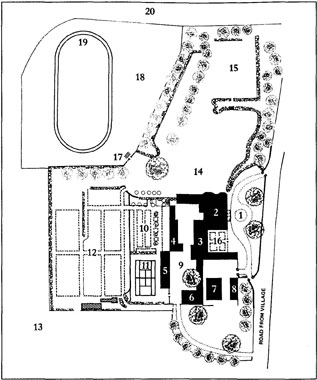

You can use this plan to see where these things were and what they looked like.

1.

Front drive

2.

Main house (Marza)

3.

Classrooms on ground floor, Night Nursery and other junior dormitories on second

4.

More classrooms (French)

5.

Art room — later, theater for play

6.

Classrooms

7.

Stables

8.

Laundry

9.

Yard

10.

Rose Garden

11.

Tennis courts

12.

Kitchen Garden

13.

Meadows and fields

14.

Lower Garden

15.

Upper Garden

16.

Tudor Garden

17.

Steps up to lawn

18.

Paddock

19.

Ring

20.

Out of bounds

More of the Lower Garden, with different angles of the house in the background.

I opened a dark green door in a brick wall and then I knew where I was again — right next to our part of the house. I ran up to the big room called the Nursery.

Matron was sitting at a round wooden table, folding clothes. She was sixteen-and-a-half, but she seemed older than our baby-sitters in America — she seemed like a grown-up, not a teenager, maybe because she was so big. She was almost as tall as my father and I think even bigger.

Everyone called her “Matron,” but (as I found out later — I didn’t remember any Matrons in the school stories) it wasn’t her name: it was her job. I don’t know what she did while we were having lessons, but when we weren’t, she was usually in the Nursery, or some place else where we could easily find her and talk to her. She also put us to bed, gave us our baths, and looked after us when we were ill.

The matron at English boarding schools for younger children looks after the girls somewhat the way a nanny does and is called “Matron,” just as nannies are called “Nanny.” The Matron my first term was unusually young, interested in us, and fun.

Everything about her was round: she had a round face and shiny blonde hair in a round bun at the back, very fair skin, and round navy-blue eyes. That day she was wearing a navy-blue dress with a white collar and white rims on the sleeves. This was her first term at Sibton Park, too; she had just left school herself and was only going to be at Sibton Park for one term — she would be going to the university in September. She wanted to be a writer, too. She had told me all this after breakfast, when she was moving me into my new dormitory and showing me around. I liked her.

When I came in from the meadow, she said, “My goodness, Libby, look at your jumper! Whatever have you been doing?”

I looked. My sweater (“jumper”) and culottes and even my socks were covered with horse hairs. I told her what had happened.

“That must have been Nella. A big gray mare?”

“I don’t know if it was a mare or not — it was big, and seemed old.”

“She is. Twenty at least.”

I was pleased that I’d guessed right about the age and decided it would be all right to ask a question.

“Why do you think she did that?”

“Scratching herself.”

She explained that horses’ faces get very itchy and that they can’t scratch themselves or each other, and that a person in wool clothes is the very best thing.

“For their backs they roll on the grass,” Brioney (the seven-year-old in my new dormitory) said — she was lolling on a bed by the window. “Like this!”

She rolled on the bed, rubbing her back into it, and waved her arms and legs. Her feet were big — although she was younger, Brioney was much bigger than I was. She had big bones and big round eyes that were so blue they sometimes looked green, and strong bones in her cheeks — even her mouth was big. That might make her sound ugly but she wasn’t — later one of the seniors said Brioney would grow up to be “a beauty.” She was kind of babyish, though.

While Brioney was rolling around like a horse itching its back, Clare came to the door. She was in my new dormitory, too, and she was my age. She was a new girl as well. Her last name was Sweeting and she seemed sweet, but I liked her. She had blonde hair and very fair skin; everything about her was light — even her voice.

She came into the room quietly, and then she asked me, kind of shyly, if I would like to go for a walk with her.

“Sure!” I said.

Brioney sat up eagerly, as though she wanted to go too, but Matron said, “Stay here with me, Brioney — you can help butter the bread.”

So Clare and I went by ourselves. We were wearing exactly the same clothes: fawn-colored jumpers (we each had on a pullover with a cardigan over it), gray wool culottes, and fawn-colored knee socks. Only our shoes were different. Having a uniform was kind of fun, I thought.

She told me that she had an older sister named Carol who had been at Sibton for two years. I didn’t say anything, and there was a little pause.

Then she asked me what my “hobbies” were.

“What do you mean?” I said. I thought of the school stories. “Things like stamp collecting?”

“Well, yes. Things you’re interested in — that you do just for the fun of it.”

Playing isn’t really a hobby.

“Does writing stories count as a hobby?” I said.

“Yes, of course,” she said.

“Well, then: writing. I do write, quite a lot — I’m going to be an author when I grow up.” Clare looked interested, and asked more questions. I told her one of the Crazy Old Witch stories, and when the Witch said “My foot!” she laughed. Talking about my writing felt strange, but fun, and after that we talked about lots of other things. We walked around the fields talking until Brioney came out and said it was time for dinner.

Manners and Matron

All three of us walked to the Dining Hall together, and when we got there, Matron told me that I would be sitting next to her at meals, so she could teach me to “eat properly.”

That, I learned over the next few days, meant always holding your fork in your left hand, and your knife in your right, and eating from the back of the fork, instead of the front. You used the knife to push food onto the back of the fork. It was hard, especially with peas, which we had a lot — they were always sliding off the fork, and of course, you couldn’t use your fingers to push them back on.

There were lots of other eating rules, too, that we don’t have in America: When you butter bread, put the butter on your plate; then (with your butter knife, not a regular knife) put a little bit — just what you’re going to eat at that bite, no more — on the bread, eat it, then, when you’re going to take another bite, put on a little more. NEVER butter the whole piece, never scrape your knife on the side of the plate.