Bloody Crimes (48 page)

Three months later, Miles would be relieved of his command. The fifteen-month assignment had not been to his liking, but he resented leaving his post under a cloud. His career survived the embarrassment, and he enjoyed future success in the west fighting Indians, and rose in rank until he commanded the entire U.S. Army.

In the summer of 1866, two ghosts from the Lincoln assassination visited Fort Monroe. On June 5, Surgeon General Joseph A. Barnes called upon Davis. Barnes had watched Lincoln die. On August 12, Assistant Surgeon General Charles H. Crane visited Davis. He and Barnes had witnessed the autopsy and watched Curtis and Woodward cut open Lincoln’s head and remove his brain. They had come to evaluate Davis’s health and to ensure that he did not die while in Union captivity. Stanton wanted no martyrs. Did Davis know what they had seen? No records survive to indicate whether the doctors discussed the assassination with him.

By the fall of 1866, the government had still taken no action

to prosecute Davis for treason. He welcomed his trial, whatever its result. If he was acquitted, then the South was not wrong—it did have the constitutional right to leave the Union, and secession was not treason. If he was found guilty, he was happy to suffer on behalf of his people. His death, he believed, would win mercy for the South. The U.S. government wanted neither result. A federal court verdict declaring secession not treasonable would overturn the whole purpose and result of the war. Some of the ablest attorneys in America had offered to defend Davis, and a guilty verdict was by no means certain. And a guilty verdict, followed by Davis’s execution, would create a martyr and might inspire the South to rise up again. John Reagan said it would be best for all concerned to release Davis: “I urged that the welfare of the whole country would be subserved by setting him free without a trial; for the South it would be a signal that harsh and vindictive measures were to be relaxed; and for the North it would indicate that they were willing to let the decision of the right of secession rest where it was and not try to secure a judicial verdict…the war had passed judgment and that hereafter secession would mean rebellion.”

While the government dithered, Davis lingered in legal limbo through the winter of 1867. But by the spring, the federal government finally decided that it wanted Davis off its hands. He would be released on bail, preserving the right to try him at some future time. By prearrangement, his attorneys would initiate proceedings to free him and the government would not oppose them. On May 8, 1867, former president Franklin Pierce visited Davis in prison and congratulated him on his pending release.

On May 10, the second anniversary of Davis’s capture, a writ of habeas corpus was served on the commander of Fort Monroe. At 7:00

A.M.

on May 11, Burton Harrison, Joseph E. Davis, Jefferson’s brother, and several others escorted the former Confederate president, not quite a free man yet, to the landing at Fort Monroe, where he boarded the steamer

John Sylvester

for Richmond. At 6:00

P.M.

Davis reached

Rocketts, the same place where, two years earlier, Abraham Lincoln had landed in Richmond to a tumultuous welcome from the city’s slaves. Now the white citizens welcomed Davis back to his old capital. As he passed, men uncovered their heads and women waved handkerchiefs. “I feel like an unhappy ghost visiting this much beloved city,” Jefferson told Varina. A carriage drove them to the Spotswood Hotel, where they were taken to the same rooms they occupied in 1861.

On Monday morning Davis and his counsel appeared in federal court, in the same building once occupied by his presidential office. The $100,000 bond was signed by an unexpected list of names: Davis, Horace Greeley, Cornelius Vanderbilt, and Gerrit Smith, the famous abolitionist, and one of the “Secret Six” who had backed John Brown. Smith proclaimed that the war had been the fault of North and South: “The North did quite as much as the South to uphold slavery…Slavery was an evil inheritance of the South, but the wicked choice, the adopted policy, of the North.” After Davis was freed on bail, he left the courtroom and was surrounded by a crowd of supporters; according to his principal legal counsel, Charles O’Connor, “poor Davis…wasted and careworn, was almost killed with caresses.” Davis returned to the Spotswood, where he and Varina received friends.

On May 13 Davis posted bail, the court released him, and he walked out a free man. In 1867, the Lincoln assassination conspirators were either dead or in prison, Captain Wirz had been executed for war crimes and Jefferson Davis was allowed to leave custody as a free man, never having been tried, let alone found guilty of any crime. The man who led the campaign to divide the nation, the man who gave orders to fight and kill Union soldiers, was never tried. The importance of this cannot be overstated. To Davis’s partisans, this meant that no federal court had ever ruled that secession was unconstitutional or treasonous. Thus, they believed, Davis had done no wrong. To Northerners, whatever happened or did not happen to Davis in a court of law, he remained a traitor. If he was freed, it was

for prudential reasons, to heal the wounds of war, not to achieve legal justice. His first act, one that would set the tone for the remainder of his life, was one of remembrance. He took flowers to the grave of his son Joseph Evan Davis at Hollywood Cemetery, and while there he also decorated graves of Confederate soldiers. A friend wrote to Varina Davis to assure her that in the joy over the president’s release, the people of Richmond had not forgotten their dead son: “Last Friday [June 1], Hollywood was glorified with flowers. The little one who sleeps here was not forgotten. Garland upon garland covered every inch of turf and festooned the marble that bore the beloved name, some with the touching words, ‘for his Father’s sake.’”

On June 1 a Confederate officer who had served under President Davis sent him a heartfelt letter that described the “misery which your friends have suffered from your long imprisonment,” adding that “to none has this been more painful than to me.” The letter rejoiced in Davis’s freedom: “Your release has lifted a load from my heart which I have not words to tell, and my daily prayer to the great Ruler of the World, is that he may shield you from all future harm, guard you from all evil, and give you the peace which the world can not take away. That the rest of your days may be triumphantly happy, is the sincere and earnest wish of your most obedient faithful friend and servant.” The letter was signed by Robert E. Lee.

A

fter his release, Davis was forced to ask himself questions for which he had no immediate answers. What did the future hold? Where would he go? What would he do? How would he live? How would he earn money? Like much of the South, his life was in ruins. He had lost everything. He had no cache of secret gold. His plantation was in ruins, no crops grew there, and he owned no slaves to work the fields. They had all been emancipated. Union soldiers had looted his Mississippi home of all valuables. They even stole his old love letters from Sarah Knox Taylor.

He also had to decide what he must

not

do. His behavior would be scrutinized by Northerners and Southerners alike. He vowed to do nothing to bring dishonor upon himself, his people, or the Confederacy. Because so many Southerners were poor, he decided that he would not shame himself by accepting charity from his supporters while others were in need. He would not speak publicly against the Union or Reconstruction, he decided, out of fear that his words might cause his people to be punished. Nor would he run for public office. He knew without doubt that he could be elected to any political position in the South. But to seek office, he would have to take a loyalty oath to the Union, something he would never do. To swear that oath, to recant his views, to say the South was wrong, would betray every soldier who laid down his life for the cause. He would rather suffer death. And, last, he decided he would never return to Washington, D.C., the national capital he once loved and the scene of many of his greatest achievements and happiest days.

CHAPTER TWELVE

“The Shadow of the Confederacy”

F

or the first time in his life, Davis needed a job. It was a shocking predicament for a member of the elite, planter class. But he had no choice. He needed money and stability, and the quest for it preoccupied him. For the next two years, he wandered and pursued opportunities that led nowhere. In November 1869, he was offered the presidency of the Carolina Life Insurance Company at the impressive annual salary of $12,000—nearly half the pay of the president of the United States. He took the job. But Davis’s days as a “business man” were numbered. An epidemic killed too many customers, and the economic downturn put the company out of business. Davis pursued other moneymaking opportunities, and he considered various schemes that others proposed to him, but he never achieved the financial success that he craved. Failure embarrassed him.

In 1870, the whole South mourned the death of its great general, Robert E. Lee. Davis spoke at the memorial service with sadness and great eloquence, and it was there that he found the true purpose of his remaining days—remembering and honoring the dead. Soon,

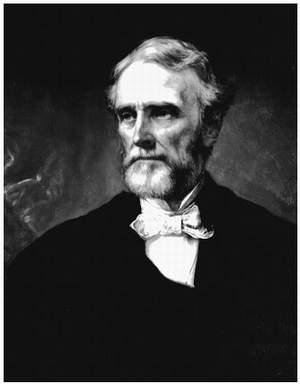

OIL PORTRAIT OF JEFFERSON DAVIS AS HE APPEARED IN THE 1870S.

the theme of “The Confederate Dead”—the idea of a vast army of the departed who haunted the Southern landscape and memory—swept the popular imagination. Soon, veterans’ groups, historical societies, and women’s associations labored to recover the dead from anonymous wartime graves, to build cemeteries for them and to mark the land where they shed their blood with monuments of stone, marble, and bronze. Later, Davis became the symbol of this movement. He was the link between the Confederate living and the dead. For now, Lee’s unexpected death was a warning to Davis that he should not wait too long to tell his story. As early as March 30, 1870, Davis told

Burton Harrison that he wanted to write a book: “It has been with me a cherished hope that it would be in my power before I go down to the grave to make some contribution to the history of our struggle.” Lee had hoped to do the same. The general had begun to gather documents. He examined his official papers. But before he could write his memoirs, he died.

In the 1870s, Davis hit his stride as a keeper of Confederate memory. He wrote articles. He read histories of the war written by generals and political leaders. He kept up an active correspondence and answered countless inquiries about the conduct of the war. He supported the creation of the Southern Historical Society. The North may have won the war on the battlefield, but the South would not lose it a second time in the books. Davis became the titular head of a shadow government, no longer leading a country, but leading a patriotic cause devoted to preserving the past.

Davis became a fixed symbol in a changing age. He witnessed the passing of an era and the rise of a different, modern America. The U.S. Army fought new wars on the western frontier, and in 1876, when America was set to celebrate its national centennial, the flamboyant Civil War general George Armstrong Custer found death at the Little Bighorn, eleven years after Appomattox. To take advantage of the patriotic fervor during the centennial, grave robbers plotted to kidnap Lincoln’s corpse and ransom it for a huge cash payment. They broke into the tomb but were arrested. Davis witnessed the industrialization of the nation, the invention of electric lights, and the first hints of America’s future role as a global power. He also witnessed the plight of blacks during Reconstruction in the postwar South, and what happened to them after 1877, when the last of the federal occupying troops returned to the North. In a few years he would read of the assassination of another president, James Garfield, who survived the Civil War only to be shot in the back at a Washington, D.C., train station.

Throughout this era, Davis experienced financial insecurity and

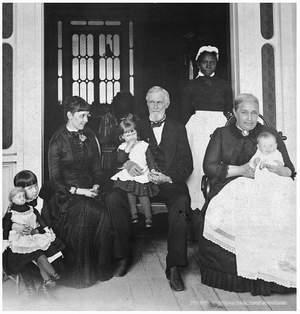

ON THE FRONT PORCH AT BEAUVOIR.

domestic instability. He lacked a proper income or a real home. In 1877, he found his sanctuary at last. A longtime friend and widow, Sarah Dorsey, invited Davis to visit her Mississippi Gulf Coast estate, Beauvoir, near Biloxi. The visit became permanent, and Dorsey willed the property to Davis upon her death. Beauvoir became his haven. It relieved him of significant financial distress, gave him a place to live, and allowed him to finish his book. As Davis labored to complete his memoirs, he also found here, fourteen years after the end of the war, and twelve years since his freedom, a kind of peace. As the years passed at Beauvoir, he became more handsome. His face softened.

Photographs from the Gulf coast years capture a gentle smile absent from photos taken earlier in his life, in the 1850s and 1860s.