Bloody Crimes (45 page)

Now that Davis and all the Confederate armies east of the Mississippi River had surrendered, the Union was ready to celebrate the end of the war in style. On May 18, Grant issued General Order No. 239, announcing that a “Grand Review” of the Army of the Potomac and Sherman’s Army of the West would take place over two days

in Washington, on Tuesday, May 23, and Wednesday, May 24. This extravaganza was rumored to be bigger than even the April 19 Lincoln funeral procession.

On May 19, Davis, aboard the

William P. Clyde,

neared Fort Monroe.

The same day, General James Wilson recommended that all of the officers and men of the First Wisconsin and Fourth Michigan cavalry regiments engaged in the pursuit of Davis below Abbeville receive medals of honor and that the reward be divided among all of the men actually engaged in the capture, with “ample provision being made for the families of the men killed and wounded in the unfortunate affair between the two regiments.”

Stanton wanted his prisoners transported in secret, and he was alarmed when he intercepted telegrams sent to Gideon Welles by two naval officers. Commander Frailey and Acting-Rear-Admiral Radford sought to inform the navy secretary that the

Tuscarora

had convoyed to Hampton Roads the vessel

William Clyde,

with Davis on board. Welles recalled Stanton’s feeling that “the custody of these prisoners devolved on him a great responsibility, and until he had made disposition of them, or determined where they should be sent, he wished their arrival to be kept a secret…He wished me to…allow no communication with the prisoners except by order of General Halleck of the War Department…and again earnestly requested and enjoined that none but we three—himself, General Grant, and myself—should know of the arrival and disposition of these prisoners…not a word should pass.”

Welles scoffed at Stanton’s obsession with secrecy: “I told him the papers would have the arrivals announced in their next issue.” But Welles indulged his military counterpart: “I, of course, under his request, shall make no mention of or allusion to the prisoner, for the present.”

Stanton, Welles, and General Grant, who was also present, discussed what to do with Varina Davis and the other women in cus

tody. Stanton exclaimed that they must be “sent off” because “we did not want them.” “They must go South,” Stanton declared, and he drafted an order dictating that course. When Stanton read the dispatch out loud, Welles could not resist toying with him: “The South is very indefinite, and you permit them to select the place. Mrs. Davis may designate Norfolk, or Richmond.”

Or anywhere. Grant laughed and agreed—“True.”

Stanton could not tolerate the former first lady of the Confederacy showing up wherever she wanted. “Stanton was annoyed,” Welles saw, and “I think, altered the telegram.” Stanton knew that if Varina returned to Washington, she could be an influential and dangerous political opponent.

O

n Saturday, May 20, Davis was two days out from Fort Monroe. In Washington, the Lincoln funeral train, its work done and now back from the thirty-three-hundred-mile round-trip to Springfield, sat at the United States Military Railroad car shops in Alexandria, Virginia. The death pageant had been a spectacular success. Now, on the heels of the Lincoln funeral pageant, Stanton, Grant, and the War Department worked on the final details for the unprecedented Grand Review—the gigantic, two-day parade, the biggest in American history—of the victorious Union armies up Pennsylvania Avenue.

In Richmond, the population labored to recover from the twin plagues of occupation and fire, not knowing that another calamity was about to befall the city. By 5:30

P.M.

Saturday, “portentous clouds” had covered Richmond. Then, as the

Richmond Times

reported, they “burst forth with vivid lightning and stunning thunder.” This “sudden and extraordinary storm” poured rain until 4:00

A.M.,

Sunday, May 21, and then, after a brief respite, continued until 1:00

P.M.

“Never within ‘the recollection of the oldest inhabitant,’” the

Times

testified, “has such a destructive rainstorm occurred in this city.” The wind and water seemed a plague of almost biblical proportions.

Indeed, “the very floodgates of heaven seemed to open. And so great was its effect that the whole valley of the city was soon submerged in water, overflowing all the streams and washing from their banks a number of small houses, trees, & c.” Wagons, furniture, supplies, and all manner of stuff were swept away and destroyed by the flood. Some people believed the Confederate capital cursed: sacked by mobs, then burned, then occupied by Yankees, and now engulfed by a great deluge. What punishment would Richmond suffer next?

CHAPTER ELEVEN

“Living in a Tomb”

O

n Monday, May 22, the night before the Grand Review, Jefferson Davis was incarcerated at Fort Monroe. He did not know whether he would ever see his wife and children again. When he parted with Varina, he told her not to cry. It would, he said, only make the Yankees gloat.

In his captivity, the jailers refused to address him as “President.” They called him “Jeffy,” “the rebel chieftain,” or “the state prisoner.” Soon, through insult, isolation, silence, shackling, constant surveillance, sleep deprivation, and dungeonlike conditions, they would seek to humiliate him and break his spirit. He was, in the words of some newspapers, the archcriminal of the age, a man “buried alive” who must never be set free.

Lincoln had once spoken of this kind of imprisonment:

They have him in his prison house; they have searched his person, and left no prying instrument with him. One after another they have closed the heavy iron doors upon him, and

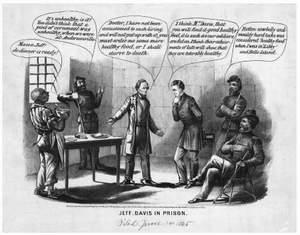

PRINTMAKERS CONTINUED TO RIDICULE DAVIS AFTER HIS IMPRISONMENT.

now they have him, as it were, bolted in with a lock of a hundred keys, which can never be unlocked without the concurrence of every key; the keys in the hands of a hundred different men, and they scattered to a hundred different and distant places; and they stand musing as to what invention, in all the dominions of mind and matter, can be produced to make the impossibility of his escape more complete than it is.

But Lincoln was not, in these 1857 remarks on the

Dred Scott

decision, speaking of Jefferson Davis. He was, instead, speaking of the “bondage…universal and eternal” of the American slave. Now, the leader of the vanquished slave empire found himself locked in a “prison house” as secure as any built during the previous two and a half centuries of American slavery. Millions of his enemies in the North hoped he would never emerge from his dungeon alive.

CONTEMPORARY SKETCH OF DAVIS IN HIS CASEMATE CELL AT FORTRESS MONROE.

T

he night Davis was placed in his prison cell, Mary Lincoln moved out of the White House. She took with her a suspiciously large number of trunks. Benjamin Brown French was not sorry to see her go. He called on her before she left the presidential mansion: “Mrs. Mary Lincoln left the City on Monday evening at 6 o’clock, with her sons Robert & Tad (Thomas). I went up and bade her good-by, and felt really very sad, although she has given me a world of trouble. I think the sudden and awful death of the President somewhat unhinged her mind, for at times she has exhibited all the symptoms of madness. She is a most singular woman, and it is well for the nation that she is no longer in the White House. It is not proper that I should write down,

even here,

all I know! May God have her in his keeping, and make her a better woman. That is my sincere wish…”

No government or military official in Washington regretted that Mary would be absent from the next day’s parade.

Early on Tuesday morning, before the Grand Review got under way at 9:00, photographers claimed their positions on the south grounds of the Treasury Building, east of the White House. From there they pointed their cameras up Pennsylvania Avenue to capture the panorama of troops marching toward them, framed by the Great Dome rising in the distance. Other cameramen took photos of the huge crowds gathered in front of Pennsylvania Avenue storefronts. At the Capitol, one photographer aimed his lens at the North Front, where crowds had gathered to watch the troops march up East Capitol Street and swing around the Capitol building on their way down the avenue. When he removed his lens cap, he froze a wondrous, ephemeral moment: blurred figures in motion; a man carrying, on a pole, a sign reading

WELCOME BRAVE SOLDIERS,

and, strolling through the frame, a young girl wearing a hoopskirt and a straw hat, trailing festive ribbons.

Gideon Welles delayed a trip south to witness the “magnificent and imposing spectacle,” and recorded in his diary:

[T]he great review of the returning armies of the Potomac, the Tennessee, and Georgia took place in Washington…It was computed that about 150,000 passed in review, and it seemed as if there were as many spectators. For several days the railroads and all communications were overcrowded with the incoming people who wished to see and welcome the victorious soldiers of the Union. The public offices were closed for two days. On the spacious stand in front of the executive Mansion the President, Cabinet, generals, and high naval officers, with hundreds of our first citizens and statesmen, and ladies, were assembled. But Abraham Lincoln was not there. All felt this.

General Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, who would receive the Medal of Honor for his defense of Little Round Top at Gettysburg, felt it too when he and his men came opposite the reviewing stand:

“We miss the deep, sad eyes of Lincoln coming to review us after each sore trial. Something is lacking in our hearts now—even in this supreme hour.”

From his front porch, Benjamin Brown French watched the Ninth Corps of the Army of the Potomac march west, down East Capitol Street on its way downtown, and to President Johnson’s reviewing stand. French, who as commissioner had draped all the public buildings in Washington in mourning for Lincoln, including the Capitol, the Treasury Department, and the White House, now decorated his own house with symbols of joy: “I put a gilded eagle over the front door and festooned a large American flag along the front of the house, the centre being on the eagle, and above the eagle, in a frame placed in the window.”

Then he went to the Capitol, climbed the narrow, twisting staircase to the Great Dome, and beheld the magnificent sight: “We went on the dome, from which we could see troops by the thousands in every direction…more than 50,000 in sight at one time, as we could see the entire length of Maryland Avenue west, Pennsylvania Avenue east, New Jersey Avenue south, and all of Pennsylvania Avenue west from the Capitol to the Treasury, and they were all literally filled with troops. It was a grand and brave sight.”

While Union troops were marching in Washington, others at Fort Monroe entered Davis’s cell and told him they had orders to shackle him. Davis saw the blacksmith with his tools and chains. He told them all that he refused to submit to the humiliation and pointed to the officer in charge and said he would have to kill him first. Davis dared his jailers to shoot him. Soldiers lunged forward to grab him, but Davis, exhibiting some of the strength he had displayed decades earlier when wrestling slaves, knocked one man aside and kicked another away with his boot. Then several men ganged up on him, seized him, and held him down while the smith hammered the shackle pins home. This was supposed to have been done in secret, but like many of the events to unfold in the days to come

at Fort Monroe, word was leaked to the press. The

Chicago Tribune

reported the scuffle, claiming in one headline that Davis was “On the Rampage.” Little did Davis know, his enemies had done him a huge favor.

D

y May 24, Lincoln’s home in Springfield, viewed by thousands of funeral visitors during the first week of May, was no longer a center of attention. The delegations of dignitaries who had lined up in front of the house to pose for dozens of souvenir photographs had all left town. But on this day an anonymous photographer, probably local to Springfield, showed up to make the last known image of the Lincoln home draped in mourning. In the photograph, the black bunting, exposed to the elements for weeks, hangs askew, windswept and weather-beaten. No one poses for the camera, and the big frame house looks abandoned, even haunted. Green leaves—new life—sprout from the tree branches that frame the image. All across the nation, people could not bear to take down their wind-tattered, sun faded, and rain-streaked habiliments of death and mourning. Better, many thought, to allow time and the elements to sweep them away.