Bloody Crimes (41 page)

The president took his eight-year-old son, Jefferson Davis Jr., shooting. Unlike the day in Richmond when Jefferson ordered pistol cartridges for Varina and taught her how to shoot a revolver in

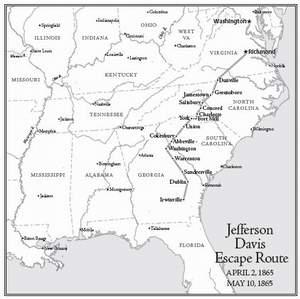

self-defense, this was for fun. The boy would have no need to defend himself with firearms. Colonel William Preston Johnston observed the target practice. The president “let little Jeff. shoot his Deringers at a mark, and then handed me one of the unloaded pistols, which he asked me to carry.” When Davis and Johnston turned their discussion to their escape route, the colonel “distinctly understood that we were going to Texas.” Johnston said that he did not think they could get there by going west through the state of Mississippi, suggesting it might be safer to make for the Florida coast and sail through the Gulf of Mexico to the Texas coast. “It is true,” Davis replied, “every negro in Mississippi knows me.” He guessed that it would be impossible to travel incognito through his home state without being recognized by at least one slave.

On May 8, Davis decided to part from his family and at dawn he rode on with his personal staff and a small military escort. By that night he had made little progress through heavy rains, and Varina’s train caught up with him in Abbeville, a speck of a town consisting of just a few buildings. When Harrison finally found Davis, he was sleeping on the floor of an abandoned house. Word of a Yankee cavalry patrol twenty-five miles away in Hawkinsville persuaded Davis that his wife’s party should drive on through the bad weather and not stop to rest. He was too tired to leave the house and come outside to see Varina. He would, he assured Harrison, catch up to them after he rested for a while in Abbeville. Later in the night, Jefferson’s party followed Varina’s, and they reunited before dawn on May 9. The two groups traveled twenty-eight miles together for the day, stopping at 5:00

P.M.

Davis decided to make camp for the night with Varina’s wagon train near Irwinville. They pulled off the road, and the pine trees helped conceal their position. President Davis’s escort did not set up a defensive camp, circling their wagons in a compact circle, picketing their horses and mules inside the ring, and pitching tents or laying out bedrolls within the perimeter. Davis was not camping on the western

plains of the frontier of his youth, and he expected no attack from Native Americans during the night. Forming a wagon train into a circle made sense on the wide open plains, but not in the Georgia pines.

If Union cavalry discovered his position and charged his camp in force, his small entourage could not outgun them, and if the federals were able to surround a small camp drawn up in a tight circle, it would be difficult for Davis to take advantage of the confusion of battle and escape. So, instead, Davis’s party pitched camp with an open plan, scattering the tents and wagons over an area of about one hundred yards. Now, any Yankee who rode into one part of the camp during the night would not be able to see to the other side of it. A small force of eight to twelve enemy cavalrymen could not gain control

of the entire camp, and the men guarding the president had a decent chance of outfighting such a small patrol.

If the chosen few of the president’s escort had come this far, now that their numbers had dwindled to less than thirty, from a force of several thousand men, they could be trusted to fight to the death to save the president and his family. If there was a fight, then Davis, unless captured at once, could escape into the woods while it was dark.

The arrangement was perfect, but for one oversight. Tonight the camp posted no guards to keep vigil through the dawn. A handful of cavalrymen, led by Captain Givhan Campbell, were out scouting instead of guarding the camp. As the members of the little caravan began to fall asleep, they faced two dangers in the night: attack from ex-Confederate soldiers—ruthless, war-weary bandits bent on plunder—or an attack from the Union cavalry, on the hunt for President Davis. It was no secret that bandits had been shadowing Varina Davis’s wagon train for several days, and they could strike anytime without warning. That was the reason Davis had reunited with Varina, instead of pushing on alone.

Davis’s aides knew that it was too dangerous for him to continue traveling with his wife’s slow-moving wagon train. “Fully realizing that so large a party [of nearly thirty people] would be certain to attract the attention of the enemy’s scouts, that we had every reason to believe [that they] were in pursuit of us,” recalled Governor Lubbock, “it was decided at noon [May 9] that as soon as we had concluded the midday meal the President and his companions would again bid farewell to Mrs. Davis and her escort.”

Davis did not plan to spend the night of May 9 camped with his wife and children near Irwinville. Unless he abandoned the wagon train and moved fast on horseback, accompanied by no more than three or four men, he had little chance of escape. By this time the Union was flooding Georgia with soldiers and canvassing every crossroads, guarding every river crossing, and searching every town.

Furthermore, the federals had recruited local blacks with expert knowledge of back roads and hiding places, to help in the manhunt for the fugitive president of the slave empire. The former slaves relished the task and its irony. Even if Davis did not know it, by May 9 he was at imminent risk of capture, and possible death. Thus, remembered Lubbock, “we halted on a small stream near Irwinville…and dinner over, saddled our horses, and made everything ready to mount at a moment’s notice.”

Burton Harrison spoke for the entire inner circle when he said that Davis needed to separate from the wagon train and entourage:

We had all now agreed that, if the President was to attempt to reach the Trans-Mississippi at all, by whatever route, he should move on at once, independent of the ladies and the wagons. And when we halted he positively promised me…that, as soon as something to eat could be cooked, he would say farewell, for the last time, and ride on with his own party, at least ten miles farther before stopping for the night, consenting to leave me and my party to go on our own way as fast as was possible with the now weary mules.

Harrison proposed that the president take Lubbock, Wood, Johnston, and possibly Reagan with him, and that Harrison remain with Mrs. Davis, the children, and the rest of the wagon train personnel. Davis told his aides that he would leave the camp sometime during the night. “The President notified us to be ready to move that night,” affirmed Reagan.

Davis told him that he would eat dinner, stay up late, and leave on horseback after it was dark. He was dressed for the road: dark felt, wide-brimmed hat; signature wool frock coat of Confederate gray; gray trousers; high, black leather riding boots, and spurs. His horse, tied near Varina’s tent, was already saddled and ready to ride, its saddle holsters loaded with Davis’s pistols.

Harrison felt sick and retired early. “After getting that promise from the President,” he remembered, “and arranging the tents and wagons for the night, and without waiting for anything to eat (being still the worse for my dysentery and fever), I lay down upon the ground and fell into a profound sleep.”

Harrison was certain that when he awoke, Davis would be gone. Captain Moody stretched a piece of canvas above Harrison’s head and lay down beside him. Several of the men, including Reagan, stayed up late talking, waiting for Davis to give the order to depart. It never came.

The delay puzzled Lubbock: “Time wore on, the afternoon was spent, night set in, and we were still in camp. Why the order ‘to horse’ was not given by the President I do not know.”

“For some reason,” Reagan said, “the President did not call for us that night, though we sat up until pretty late.”

Wood and Lubbock fell asleep under a pine tree no more than one hundred feet from Davis’s tent, with Johnston, Harrison, and Reagan sleeping somewhere between them and Davis.

CHAPTER TEN

“By God, You Are the Men We Are Looking For”

U

nbeknownst to the inhabitants of Davis’s camp, a mounted Union patrol of 128 men and 7 officers—a detachment from the Fourth Michigan Cavalry regiment—led by regimental commander Lieutenant Colonel B. D. Pritchard, was closing in on Irwinville.

Pritchard reached Wilcox’s Mills by sunset of May 9, but the horses were spent. He halted for an hour and had the animals unsaddled, fed, and groomed. Then he pushed on in the dark. “From thence we proceeded by a blind woods road through almost an unbroken pine forest for a distance of eighteen miles, but found no traces of the train or party before reaching Irwinville, where we arrived about 1 o’clock in the morning of May 10, and were surprised to find no traces of…the rebels.”

Pritchard ordered his men to examine the conditions of the roads leading in all directions, but they saw nothing to suggest that a wagon train or mounted force had passed that way. Pritchard left most of his men on one side of town and rode ahead with a few men to the other side where his main body had not been spotted and, posing as

Confederate cavalrymen, they questioned some villagers. “I learned from the inhabitants,” Pritchard recounted, “that a train and party meeting the description of the one reported to me at Abbeville had encamped at dark the night previous one mile and a half out on the Abbeville road.”

At first Pritchard suspected it was a Union camp—he knew firsthand from an earlier encounter with them that men from the First Wisconsin Cavalry regiment were in the region hunting for Davis too—but then he realized that mounted federals would not be moving with tents and wagons. Whoever was in that camp, they were not Union men. Pritchard left Abbeville and positioned his men about half a mile from the mysterious encampment. “Impressing a negro as a guide,” Pritchard recalled, “…I halted the command under cover of a small eminence and dismounted twenty-five men and sent them under command of Lieutenant Purington to make a circuit of the camp and gain a position in the rear for the purpose of cutting off all possibility of escape in that direction.”

Pritchard told Purington to keep his men “perfectly quiet” until the main body attacked the camp from the front. Tempted to charge the camp at once, Pritchard decided to wait until daylight: “The moon was getting low, and the deep shadows of the forest were falling heavily, rendering it easy for persons to escape undiscovered to the woods and swamps in the darkness.” The men of the Fourth Michigan were in place by about 2:00

A.M.

For the next hour and a half, they waited in the dark, undetected.

At 3:30

A.M.,

Pritchard ordered his men into their saddles and to ride forward: “[J]ust as the earliest dawn appeared, I put the column in motion, and we were enabled to approach within four or five rods of the camp undiscovered, when a dash was ordered, and in an instant the whole camp, with its inmates, was ours.” Pritchard’s men had not fired a shot. Pritchard exaggerated the speed with which his men had captured the camp. “A chain of mounted guards was immediately thrown around the camp,” Pritchard claimed, “and dismounted

sentries placed at the tents and wagons. The surprise was so complete, and the movement so sudden in its execution, that few of the enemy were enabled to make the slightest defense, or even arouse from their slumbers in time to grasp their weapons, which were lying at their sides, before they were wholly in our power.”

But Pritchard was not omniscient. He could only see what events transpired in front of his own eyes. Throughout the camp, individual human dramas unfolded simultaneously as the Fourth Michigan charged the tents and wagons. Before Pritchard’s men could gain full control of the camp, and before the colonel even verified that this was Jefferson Davis’s camp, gunfire broke out where Pritchard had stationed Lieutenant Purington and twenty-five men. It was a rebel counterattack, Pritchard feared. He spurred his horse past the tents and wagons and rode to the sound of the gunfire.

As Purington faced Davis’s camp, awaiting Pritchard’s signal, he heard mounted men approaching him from his rear. He stepped out from cover to halt them, and they called out that they were “friends.” But they refused to identify themselves and would not ride forward when Purington ordered them to. In response to his repeated command that they identify themselves, one of them shouted, “By God, you are the men we are looking for” and began to ride away. Purington ordered his men to open fire. The First Wisconsin fired back.

Lieutenant Henry Boutell of the Fourth heard the gunfire and rode toward Purington. “Moving directly up the road,” said Boutell, “I was met with a heavy volley from an unseen force concealed behind tree…and from which I received a severe wound.” Another man from the Fourth was shot and killed. As the battle continued, a third man from the Fourth was wounded, and several Wisconsin men were also shot. In the dark they could not see that they wore the same uniform, Union blue cavalry shell jackets decorated with bright yellow piping.

The shooting woke Jim Jones, Davis’s coachman, and he gave

the alarm. He roused William Preston Johnston, whom the charging horses had not awakened.