Blood on the Tracks: A History of Railway Crime in Britain (5 page)

Read Blood on the Tracks: A History of Railway Crime in Britain Online

Authors: David Brandon,Alan Brooke

Many courts had a considerable amount of their time taken up with cases of assault on the railways. The nature of these assaults was as varied as the people who committed them. What are we to make of the two students fined 30 shillings by Hammersmith magistrates for leaning over a division between two compartments and spitting onto the hat and a book belonging to a doctor?

At Southport the magistrates fined a solicitor aged seventy just 5 shillings when he ran out of patience and used his umbrella to show his displeasure and knock off the hat belonging to a man who, for two whole years, had refused to admit him into the compartment he habitually shared with two other men. They spent their journeys playing whist and they clearly thought this gave them exclusive rights to the occupancy of the compartment. Such a paltry fine suggests that the court sympathised with the aged but feisty solicitor.

It was possible to hire containers of hot coals for use as foot-warmers in unheated carriages on cold days. Fights were no means unknown when other passengers who could not, or would not, hire their own foot-warmers tried to place their feet so as to benefit from the heat generated by the foot-warmer

hired by another passenger who had paid for the privilege. The latter would jealously guard their source of pedal comfort against others, using physical force if necessary. Passengers were earnestly encouraged not to engage in debates with strangers about religion or politics as a way of avoiding the likelihood of fisticuffs. That these contentious issues did frequently lead to disputes with violent outcomes is shown by the records of innumerable minor courts up and down the country.

Probably for every petty case of assault or fighting that went as far as the courts and was therefore recorded, there were innumerable others where the victims or participants did not have recourse to the law. Clearly these have mostly been forgotten, but one that is still remembered occurred when four burly farmers were joined in their compartment by a large and well-built man who proceeded, without obvious provocation, to insult and curse each of them in turn and in the most scurrilous fashion.

A request that he bridled his tongue evoked the man’s wrath, and he proceeded to crank up both the sound volume and the vituperative nature of the comments he was making. Having given the man one final chance, which only unleashed a further torrent of abuse, the four farmers then waited for the next station and seized the man who they then proceeded to throw into a duck pond close by the side of the line. Serves him right.

Assault was not always intentional. A man had been attacked by footpads in the street near Willesden Junction but had scared them off when he took out his pistol and fired over their heads. So elated had he been by this robust defence of his own person and property that a few days later he was relating the event to a stranger on a train. He was warming to his theme and becoming highly excited, he decided to re-enact his reaction to the approach of the footpads. He took out his pistol and fired it. His aim was not as true as it should have been because instead of firing across his interlocutor’s head, the bullet literally made a neat parting in the latter’s hair!

An obstreperous Welsh collier attracted a short custodial sentence after he climbed out the carriage window of a compartment on a moving train on the Taff Vale Railway and rode on the roof for some distance. Clearly a man of some acrobatic ability, he then swung entirely unexpectedly through the open window of another compartment and proceeded to pull one passenger’s hair and to punch another. Earlier in the same day he had managed to break a window and assault two railway officials at Aberdare station. After all this hyperactivity a couple of months cooling off in a cell hopefully gave him time to ponder on his foolishness.

Assaults by members of the railway staff on members of the public were by no means unknown. In 1839 a Great Western Railway employee, out of uniform, became involved in a fracas going on in a compartment where two passengers were disputing the right to sit in the same seat. The Great Western

Railwayman seems to have been overzealous and, seizing one of the passengers, deposited him in a heap on the platform, a piece of officiousness for which he was fined

£

25.

It is well known that little love was lost between rival railway companies, but this usually remained on a corporate rather than a personal basis. However, in 1843 the long-standing mutual loathing between the chairman of the London & Croydon Railway and a former director of two other companies had seen a scrimmage on a station, when one hit the other with a cane only to get a neat uppercut for his efforts. A duel was arranged, but these by now had become illegal, and the would-be contestants were prosecuted and bound over to keep the peace.

Ely is a small and quiet cathedral city but the tranquillity of the station was rudely shattered one day in 1847 when a male passenger made a maniacal attack on the other travellers in his compartment. He then hit the stationmaster and had to be locked up for the night. His defence was that he had a condition whereby he lost control of his actions after imbibing alcohol; on this occasion he had drunk one brandy. The court tended towards leniency and he was fined just

£

5!

Two respectable ladies were in a London, Brighton & South Coast train heading for London one day in 1904 when they were joined by a man who immediately leant out of the window, shouting and gesticulating. Then, so the ladies claimed, he took out a knife and lunged at one of them, unexpectedly and without provocation. Nothing daunted, one of the ladies grabbed the knife, passing it to her friend who threw it out of the window. Perhaps the man did not expect such a doughty response because he quickly found himself pinioned in a corner of the carriage until East Croydon, where the station officials were alerted and he was arrested. His defence that he had simply taken the knife out to trim his cigar was rejected and he was sentenced to hard labour.

Railways provided a host of new opportunities for Britain’s criminal elements. The environs of stations, goods depots and marshalling yards provided a myriad of opportunities for theft and robbery. One type of robbery which did not necessarily involve violence was that usually employed by small syndicates who lured unwary or credulous passengers into card games or other games of chance. The usual procedure was for a group, usually of three or four men, to enter a railway compartment on a train going a considerable distance. They did this when they had espied one or more likely marks, but they took their place on the train as if they did not know each other.

A few minutes into the journey one of the men would take out a pack of cards and suggest a game or two to while away the time. His unacknowledged accomplices would agree and might then invite anyone else in the compartment

to join them. If this happened, then the stranger would be allowed some useful initial wins and, as his enthusiasm and greed grew, the stakes rose correspondingly. The card sharps, however, were often highly skilled at taking their victim along with them but the outcome was usually the same – the victim was fleeced, yet reluctant to inform friends or authority for fear of looking stupid.

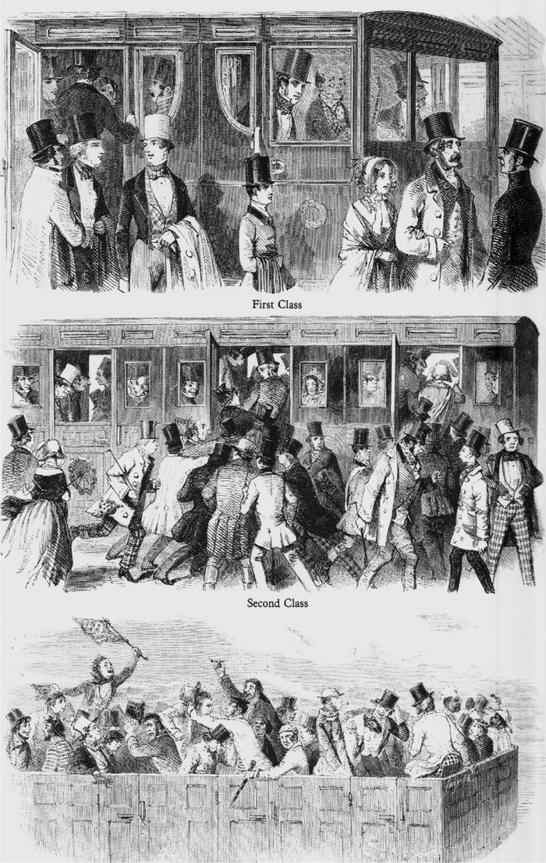

Satirical depiction of the type of public behaviour expected from, respectively, first, second and third-class early railway passengers. In reality the biggest rogues were probably in the first class.

The activities of these robbers of the iron road caused a newspaper correspondent to call for the return of Dick Turpin who he thought a capital and upright fellow compared to these devious cowards who infested Britain’s railway carriages. Sometimes these crooks threatened their victims with a dusting-up if they did not join the card games.

Pickpockets found rich reward for their efforts in densely packed railway stations and within crowded carriages. In the latter a common ploy was for a pickpocket with charm and plausibility to express concern for a wealthy looking traveller and offer to swap seats, away from a draught, for example. The thief would have already noted the disposition of likely valuables about his victim’s person, and in the minor melee created by changing seats in a crowded compartment would have deftly removed these items. We should not underestimate the skill required not only in taking the items without detection, but also in picking the right victim, obtaining agreement for the move, and for timing this just before a station stop where the pickpocket of course left the train and disappeared.

An investigator for

Tit-Bits

interviewed an instructor in the art of picking pockets who declared proudly that it was every bit ‘as much a fine art as pianoforte-playing or high-class conjuring’. The experienced and successful thieves were members of the ‘swell mob’, prominent in the hierarchy of the criminal world, and always clean and respectably well dressed. Their resourcefulness and ingenuity could be quite extraordinary. Pickpockets, of course, still ply their trade on today’s railways, crowded trains on the London Underground being a favoured hunting ground. They work in small groups, and the villain who actually does the stealing quickly and surreptitiously passes the items on to others in the syndicate. Few victims realise that they have been robbed until later, by which time they may be far from the scene.

Another different kind of villain was, and is, the luggage or baggage thief. The extent of their depredations is indicated by the fact that in the 1870s on the Eastern Counties Railway seventy-six passengers lost items of luggage in just one day. One of the most spectacular hauls made by such thieves occurred in the 1870s at Paddington station of the Great Western Railway. A member of the Countess of Dudley’s entourage foolishly placed her employer’s jewel box on the floor for a few seconds while helping a colleague. It vanished in a trice. The contents, which consisted of diamonds worth

£

50,000, were never recovered. Perhaps the offered reward of

£

1,000 was insufficient.

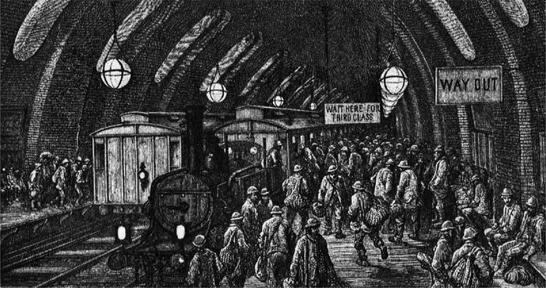

A drawing by the French artist Gustav Dore of a workman’s train on the Metropolitan Railway. Probably few thieves and pickpockets would be at work at this time of day but crowded, ill-lit platforms on the early underground were a happy hunting ground for the light-fingered fraternity.

The thief who picked up a package from a Euston to Liverpool train in 1907 must have been well pleased when he found it contained 2,000 gold half-sovereigns. Determined thieves have found ways to break into left-luggage lockers and others have forged cloakroom tickets in order to claim deposited items belonging to other people.

Those who stole pieces of luggage can never have been absolutely certain what these would contain, and must occasionally have had red faces when the contents of the stolen items were revealed as worthless. Dirty washing being taken to the laundry was one such item. A man was convicted at Taunton in 1892 for stealing a valise. It contained travellers’ samples of false teeth.

What about the man who illicitly took a station barrow to remove a heavy box, only to find when he had trundled it out the station environs that it contained turnips – nothing but turnips! This vegetable has never had much of a street value. However, the youth of fifteen who feloniously removed a hamper containing four dozen live rabbits found a ready market for them in the streets of Derby. The magistrates took a dim view of this enterprise and gave him two months of hard labour.