Blood Brotherhoods (67 page)

Read Blood Brotherhoods Online

Authors: John Dickie

Pupetta toying with a string of pearls. Pupetta stroking her long dark hair. Pupetta leaning against a tree. Pupetta in a prison smock. Pupetta in happier days. Pupetta holding her prison-born baby. When both Corso Novara murders were brought to court in a unified trial, it was Pupetta’s photo that newspaper readers were hungry to gaze at, and she obliged them by posing like a Hollywood starlet. But who was the cherubic girl in the pictures, and what had turned her into a murderer? Was she a gangland vamp, or just a widowed young mother, crazed by grief?

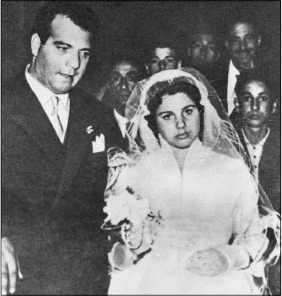

Camorra bride. Pupetta Maresca marries her ‘President of Potato Prices’, Big Pasquale from Nola (1954). She would soon be a widow, and a killer.

Pupetta Maresca gave her own response to these questions as soon as she took the witness stand: her opening gambit was ‘I killed for love.’ She admitted shooting Big Tony from Pomigliano, and maintained that he, along with another wholesale greengrocer called Antonio Tuccillo (known, prosaically, as

’o Bosso

—‘the Boss’), had ordered Big Pasquale dead. Big Pasquale had said as much to her on his deathbed, or so Pupetta claimed. Therefore this was a crime of passion, a widow’s vengeance visited on her beloved husband’s assassin. One correspondent, recalling Puccini’s tragic opera about a woman driven to avenge her murdered lover, toyed with the idea that Pupetta was a rustic Tosca.

This was the Pupetta that the public wanted to see—or at least part of it did. It was blindingly obvious that there was a mob backdrop to the story. Newspapers in the north had started a full-scale debate about the ‘new camorra’. But in Naples the idea that the camorra might not be dead after all still put people on edge.

Roma

, the newspaper that supported Mayor Achille Lauro, was as keen as ever to paint a sentimental gloss over organised crime. Lauro’s Naples would never give in to any prejudiced northerner who tried to use these tragic murders as a pretext to bring up the camorra again.

Roma

, and with it part of Neapolitan public opinion, took Tosca-Pupetta to its heart and pleaded with the judges to send her home to her baby.

But this was not the real Pupetta. To many in court, it seemed that she was deliberately playing up to the Tosca comparison. She spoke not in her habitual dialect, but in a self-consciously correct Italian. As one correspondent noted, ‘Pupetta is trying to talk with a plum in her mouth. She says, “It’s manifest that” and “That’s what fate decreed”—phrases that wouldn’t be at all out of place coming from the mouth of a heroine in a pulp novel written to have an impact on tender hearts and ignorant minds.’

The cracks in both her courtroom persona and her line of defence quickly began to show. Her melodramatic posturing did not sit easily with her lawyer’s best line of argument: that she had been threatened and attacked in Corso Novara by Big Tony from Pomigliano, and that she shot him in self-defence. Indeed Pupetta managed to put a hole in her own case with the first words she spoke to the court: ‘I killed for love. And because they wanted to kill me. I’m sure that if my husband came back to life, and they killed him again, I would go back and do what I did once more.’

The prosecution did not need to point out that a homicide could be a crime of passion, or a desperate act of self-defence. But it could never be both.

Pupetta was asked whether her family had a nickname in Castellammare. She squirmed, and dodged the issue for a while. When she finally answered she could not help the look of pride that crossed her face: ‘They call my family

’e lampetielli

,’ she admitted—the ‘Flashing Blades’. The Marescas were a notoriously violent lot, with criminal records to go with their nickname. Young she may have been, but Pupetta herself had already been accused of wounding. Her victim withdrew the charges, for reasons that are not hard to imagine.

One of Pupetta’s main concerns during the trial was to absolve her sixteen-year-old brother Ciro of any involvement in the murder. Ciro, it was alleged, had been next to Pupetta in the back seat of the FIAT 1100, and had fired a pistol at Tony from Pomigliano. The boy’s defence was not helped by the fact that he was still on the run from the law at the time of the trial.

But it may not just have been her brother that Pupetta was trying to shield. Ballistics experts never ascertained exactly how many shots were exchanged—twenty-five? forty?—because the holes spattered across the walls in Corso Novara could feasibly have been the result of previous fruit-related firefights. But it is quite possible that Pupetta and her brother Ciro were not the only people attacking Big Tony. If so, then ‘Tosca’ had actually been leading a full-scale firing party, and had embarked on a military operation rather than a solitary, impulsive act of vengeance.

Through the fissures in Pupetta’s façade, post-war Italy was getting its first glimpses of a deeply rooted underworld system in the Neapolitan countryside, a system that no amount of stereotypes could conceal. Pupetta was a young woman profoundly enmeshed in the business of her clan. And that clan’s business included her marriage: far from being a union of Tarzan and a fairy princess, this was a bond between a prestigious criminal bloodline like the ‘Flashing Blades’, and an up-and-coming young hoodlum like Big Pasquale. The world of the Campanian clans was one whose driving force was not the heat of family passions, but a coldly calculating mix of diplomacy and violence. Shortly before either of the fruit-market murders, a set-piece dinner for fifty guests was held. It seems that the dinner was a celebration of a peace deal of some kind between Big Pasquale and Big Tony from Pomigliano, the man Pupetta would eventually murder. No one could say with any certainty what had been said and agreed round the dinner table. What was obvious was that the peace deal quickly broke down. Yet even after Big Pasquale’s death, the diplomatic efforts continued: there were frequent contacts between Big Tony from Pomigliano’s people and Pupetta’s family. Were they trying to buy peace with the young widow’s clan? To stop the feud interfering with business?

These and a dozen other questions were destined to remain without a clear answer at the end of the hearings, largely because, once Pupetta had given evidence, the rest of the trial was a parade of liars. The refrain was relentless: ‘I didn’t see anything’, ‘I don’t remember’. Only one man was

actually arrested in court: he had flagrantly tried to sell his testimony to whichever lawyer was prepared to pay most. But many others deserved the same treatment. The presiding judge frequently lost his patience. ‘You are all lying here. We’ll write everything down, and then we’ll send up a prayer to the Lord to find out which one is the real fibber.’

As the Neapolitan newspaper

Il Mattino

commented, whether they lied for the prosecution or lied for the defence, most of the witnesses were people ‘from families where it is a rare accident for someone to die of natural causes’. The young blond man in the slate-grey suit who had gunned down Pupetta’s husband was called Gaetano Orlando. His father, don Antonio, had been wounded in an assassination attempt six years earlier. In revenge, Gaetano ambushed the culprit, but only succeeded in shooting dead a little girl called Luisa Nughis; he served only three years of a risible six-year sentence. Big Tony from Pomigliano’s family were even more fearsome: all three of the dead man’s brothers worked in fruit and vegetable exports with him; all three had faced murder charges; and one of them, Francesco, gave evidence in dark glasses because he had been blinded in a shotgun attack in 1946.

Jailbirds and thugs they may have been, but these were people with drivers and domestic servants, accountants and bodyguards. They owned businesses, drove luxury cars and wore well-tailored suits. Big Pasquale’s uncle, a man with an uncanny resemblance to Yul Brynner, now spent much of his time gambling in Saint Vincent and Monte Carlo—this despite having served twenty years for murder in the United States. The grey-suited Gaetano Orlando was the son of a former mayor of Marano, and the family firm had recently won a juicy contract to supply fruit and vegetables to a city hospital consortium. The young killer himself personally took charge of selling produce in Sicily, Rome, Milan and Brescia.

By this stage, the most astute observers of the case were less interested in the beguiling figure of Pupetta than in just how these violent men were making money from the vast agricultural production of the Campania region. Something Pupetta said early in proceedings opened a chink in the wall of

omertà

. She referred to Big Pasquale as the ‘President of Potato Prices’. He was the man who determined the wholesale price of potatoes across the marketplace. The other man murdered in Corso Novara, Big Tony from Pomigliano, was also described as a President of Prices.

So what exactly did a President of Prices do? Pupetta put a fairy-tale gloss on her husband’s role. Her Tarzan fixed potato prices in the interests of the poor farmers, she said. He was an honest man, who was hated by other more exploitative business rivals. This account is no more credible than the rest of Pupetta’s evidence. What seems likely is that a President’s power, as is always

the case with Italian mafia crime, was rooted in a given territory where he could build an organisation able to use violence without fear of punishment. His men would approach the smallholding farmers offering credit, seed, tools and whatever else was needed for the next growing season. The debt would be paid off by the crop, for which a low price was settled before it was even planted. Bosses like Big Pasquale or Big Tony were able to deploy vandalism and beatings systematically to quell any farmer who had enough cash or chutzpah to try and operate outside of the cartel. By controlling the supply of fruit and vegetables in this way, men who combined the roles of loan shark, extortionist and commercial middle-man could set the sums to be paid when the lorryfuls of produce were unloaded under the hangars in the Vasto quarter of Naples.

The many slippery testimonies at the Pupetta Maresca trial mean that we have to use educated guesswork to put more detail into the picture. It seems likely that the various Presidents from perhaps fifteen different towns in the Naples hinterland (Big Pasquale from Nola, Big Tony from Pomigliano, and so on) met regularly in Naples to hammer out prices between them. Because they all controlled the supply of a variety of different foodstuffs, they agreed to give the initiative in deciding the price of single fruits and vegetables to Presidents whose territory gave them a particular strength in that particular crop: hence Big Pasquale’s potatoes.

While this might seem a corrupt and inefficient system, it had distinct advantages for any national or international company that came to source produce at the wholesale market in Naples. Firms such as the producers of the canned tomatoes used on pasta and pizza would look to the Presidents of Prices for guarantees: that supply would be maintained; that prices would be predictable; and that the deals done face to face on the pavements of Corso Novara would be honoured. In return for these services, the Presidents of Prices took a personal bribe. Big Pasquale is reputed to have taken a 100 lire kickback on every 100 kilos of potatoes unloaded at the market. According to one testimony, the President of Potato Prices could send as many as fifty lorry-loads of spuds a day to the market—equivalent to some 750,000 kilos. If these figures are right, Big Pasquale could earn as much as $12,000 (in 2012 values) on a good day. And this does not take into account the money he was bleeding from the poor farmers, and the profit he made on the fruit and vegetables he traded in.

Later investigations showed that livestock, seafood and dairy produce were as thoroughly controlled by the camorra as was the trade in fruit and vegetables. Indeed, Naples did not even have a wholesale livestock market—all the deals were done in the notorious country town of Nola from which Big Pasquale took his name. According to one expert observer, ‘The

underworld in the Nola area willed and imposed the moving of the cattle market from Naples to Nola.’

Among the questions that remained unanswered by the Pupetta affair was one concerning the links between the rural clans and politicians. It is highly likely that the mobsters of the country towns acted as vote-hustlers in the same way as the

guappi

of the city.

Then there was the question of the relationship between these country clans and the urban crime scene. The wholesale greengrocery gangsters certainly made the

correntisti

of the urban slums look like small-time operators by comparison. The past may provide a few clues as to the links between the two. Big Pasquale from Nola, Tony from Pomigliano and their ilk have a history that remains largely unwritten to this day. Nevertheless, in the days of the old Honoured Society of Naples, the strongest Neapolitan

camorristi

were always the ones who had business links to country towns like Nola. The real money was to be made not in shakedowns of shops and stalls in the city, but upstream, where the supplies of animals and foodstuffs originated. Outside Naples, major criminal organisations certainly survived the death of the Honoured Society, and may well have continued their power right through the Fascist era. So the ‘new camorra’ revealed by the Pupetta case was not new at all.