Blood Brotherhoods (63 page)

Read Blood Brotherhoods Online

Authors: John Dickie

On the day Castagna’s victims were buried, the only people in Presinaci who dared join the funeral procession were

Carabinieri

in their dark parade uniforms. A single child was spotted scuttling out from a doorway to throw a bunch of flowers onto the last coffin of the five. The sound of his mother’s imploring wail followed him into the street, and he immediately hurried back indoors.

As the search for the Monster went on, the press began to ask questions. Something about the calm with which he had gone about the slaughter suggested that he was not entirely insane. But what logic could there possibly be to the murder of five seemingly innocent people, two of them women, and all of them old? Who were the ‘friends’ and ‘two-footed wolves’ that he said he was looking for? Initial speculation concentrated on Castagna’s criminal record: he had served three years in prison for attempting to murder Domenicantonio Castagna, the distant cousin whose mother was the first to fall on that terrible Sunday. Some of the other victims seemed to have a connection with the same case. Was the Monster, like the King of Aspromonte all those years ago, taking vengeance on those who had testified against him? Another theory was that he was restoring his family’s slighted honour by killing the woman who had spurned his brother.

The Communist press saw things differently, emphasising the social background to the tragedy. The correspondent for

L’Unità

, the Partito Comunista Italiano’s daily, interviewed a comrade from the area who complained that bourgeois journalists from the north were having fun portraying Calabrians as a ‘horde of ferocious people’. The real cause of Serafino Castagna’s madness was poverty and exploitation. Why couldn’t they make the effort to understand that?

Fragments of a more far-fetched explanation for Serafino Castagna’s rage also surfaced from the well of village gossip. The first person to speak to journalists was, like Castagna, a farm labourer. Skulking by a wall, and refusing to give his name, he warily muttered something about a secret society in Presinaci. But the press remained sceptical:

There have been rumours that Serafino Castagna is affiliated to the ‘Honoured Society’, a kind of Calabrian mafia. But the society’s existence is very problematic. Supposedly this ‘society’ gave Castagna until 20 April to eliminate a man who had come into conflict with it. But it seems that these reports are baseless.

The Monster of Presinaci could not be a member of the Calabrian mafia for the simple reason that there was no such thing. On that count, the most authoritative voices were unanimous.

Then, some three weeks after going on the run, Castagna sent a forty-page memoir to the

Carabinieri

that explained that he was a sworn affiliate of what he called the ‘Honoured Society of the Buckle’; he also referred to it as the ‘mafia’.

Castagna was finally arrested after sixty days. Once in the hands of the law, he told everything he knew about the Honoured Society, supplying the authorities with a great many names and evidence to incriminate them. Within forty-eight hours of Castagna’s capture, fifty members of the criminal brotherhood were detained. More arrests followed. Apparently the existence of the Calabrian mafia was not quite so ‘problematic’ after all.

In jail, the Monster of Presinaci even went on to convert the memoir he had sent to the

Carabinieri

into an autobiography. Indeed, he was the first member of the Calabrian mafia ever to tell his own story.

You Must Kill

, as Castagna’s autobiography is called, solved the mystery of why its author embarked on his desperate rampage. But it is also a very important historical document: it is post-war Italy’s primer on the organisational culture of the criminal brotherhood that is now known as the ’ndrangheta.

Serafino Castagna wrote that he was born in 1921, and grew up in a downtrodden peasant family. He was taken out of school to herd goats, constantly taunted for his disability, and maltreated by his violent father. He first heard about the Honoured Society when he was fifteen. Already, at that age, he would spend long days hoeing the family’s field. Working in the adjacent plot was Castagna’s cousin, Latino Purita, who was ten years older, and who had just been released from a jail sentence for assault. One day, when the time came for a rest, Latino started to talk to Castagna about ‘the honesty that a man must always have’, and said that ‘to be honest, a man had to be part of the mafia’. Captivated by what his cousin had said, Castagna underwent a five-year apprenticeship, stealing chickens and burning haystacks on Latino’s orders. He asserted his manhood by stabbing another youth who had poked fun at his walk. Then, on Easter Monday 1941, he underwent the long oathing ritual that began as follows:

‘Are you comfortable, my dear comrades?’ the boss asked.

‘Very comfortable,’ came the reply from the chorus of

picciotti

and ranking

mafiosi

around him.

‘Are you comfortable?’

‘For what?’

‘On the social rules.’

‘Very comfortable.’

‘In the name of the organised and faithful society, I baptise this place as our ancestors Osso, Mastrosso and Carcagnosso baptised it, who baptised it with iron and chains.’

Respecting the ‘social rules’ in Presinaci was a low-key business. There were meetings to attend, of course, and procedures to learn. But Presinaci

mafiosi

also spent a great deal of time hanging out in the tavern and spinning yarns. Castagna particularly loved to hear tales of Osso, Mastrosso and Carcagnosso, the Spanish knights who were the legendary founders of all three Honoured Societies.

The Presinaci gang had a court, known as the ‘Tribunal of Humility’. Among the minor penalties that could be handed down by the tribunal were shallow stab wounds, or the degrading punishment known as

tartaro

—‘hell’. The leadership inflicted ‘hell’ on any affiliate who displayed cowardice, or arrogance towards his fellows. They summoned him to the centre of a circle of affiliates and told him to remove his jacket and shirt. A senior member then took a brush and daubed his head and torso with a paste made from excrement and urine.

Sex and marriage generated many of the tensions that the Tribunal of Humility tried to manage. One of Castagna’s brothers was banned from the tavern for ten days and given a fine of one thousand lire. His offence was to

have violated an agreement with another

mafioso

to take it in turns sleeping with a girl they both coveted.

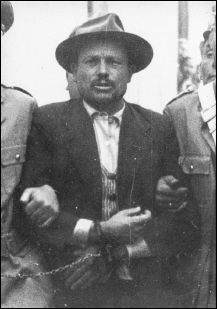

The Monster of Presinaci. Following his murderous rampage in 1955, Serafino Castagna told the authorities about the Honoured Society of Calabria.

In Presinaci, the Honoured Society always made its presence felt in public spaces, key moments of community life; it monopolised folk dancing, for example. Castagna recalled: ‘During religious festivals we in the society always tried to take charge of the dancing, so as to keep the non-members away from the fun.’ The

mastro di giornata

(‘master of the day’, the boss’s spokesman) would call each of the gang’s members to dance in order of rank. On one occasion that Serafino Castagna recalled, a non-member who tried too hard to join in was clubbed brutally to the ground.

In January 1942, the war brought an early interruption to Castagna’s criminal career. Despite his health problems, which included recurrent malaria, he was conscripted into an artillery regiment. After the collapse of the Italian army in September 1943, he managed to escape through both German and Allied lines until, ragged and hungry, he reached home to resume his journey towards the bloodbath of 17 April 1955.

With the Second World War over, life in Presinaci returned to its grindingly poor normality. The Honoured Society began to intensify activities as its leaders came back from wherever they had been scattered by the conflict. The number of arson attacks and robberies increased. Contacts with branches in other places became more regular. The Tribunal of Humility held more frequent sessions. Crimes became more ambitious and violence more frequent: Castagna confronted and stabbed a man against whom he bore a petty grudge. A readiness to kill increasingly became an almost routine test that the gang’s leaders set for the members. The climate grew more thuggish still when Latino Purita, Castagna’s ‘honest’ cousin, became boss after his predecessor emigrated.

Castagna first got into serious trouble when he was ordered to exact a fine of one thousand lire from a new affiliate who had been gossiping about the society’s affairs to a non-

mafioso

. Castagna’s instructions were to execute the offender if the money was not forthcoming. The affiliate in question was Domenicantonio Castagna, the distant cousin whom Castagna tried to kill first of all on the day, five years later, that he committed his outrages. Castagna and Domenicantonio got into a scuffle over money, a municipal guard intervened, and Castagna ended up shooting Domenicantonio in the chest. As luck would have it, Domenicantonio survived. But Castagna was caught and imprisoned for wounding him.

Castagna tells us that the Society failed to help him in prison as he had been promised. Not only that, but when he was released in the final days of 1953, the Society immediately reprimanded him for failing to kill Domenicantonio.

He was told that the only way to restore his reputation was by killing the municipal guard who had intervened in the scuffle. Castagna appealed against the decision, and obtained a little breathing space: the bosses decreed that he still had to kill the guard, but that he could wait until his period of police surveillance came to an end in the spring of 1955.

Castagna was trapped. If he committed the murder of a public official, he knew that he would probably spend the rest of his life in prison. But he could also envisage the catastrophic loss of face that would ensue if he betrayed his mafia identity and talked to the authorities: ‘Nobody would give me any respect, not even people who did not belong to the Society.’ As the deadline for vendetta grew near, he began to be tortured by nightmares about cemeteries, ghosts and wars. In the end, he made the irrevocable decision to refuse to obey, and to kill those who had ordered him to kill. He prepared himself for the coming battle by writing down everything he knew about the Honoured Society, and with it a list of the twenty members he wanted to murder. Then he prepared his last meal of fried eggs.

Castagna’s plans misfired grotesquely. Only one of his victims, the last, was a member of the Honoured Society. The others were only obliquely connected to his real targets, if they had any connection at all. This was no grand gesture, but a venting of accumulated rage and desperation.

Much of the criminal subculture that the Monster of Presinaci described in his memoir is still in use in today’s ’ndrangheta. Rituals and fables help forge powerful fraternal bonds, moulding the identity of young criminals, giving them the sense of entitlement they need to dominate their communities. If Serafino Castagna’s five murders teach us one thing, it is that the ’ndrangheta subculture can exert extreme psychological pressures.

But to the police and judiciary of the 1950s, much of Castagna’s account seemed like so much mumbo jumbo. Indeed, this was a picture of the Calabrian mafia that flattered one of Italy’s most enduring and misleading misconceptions. Even many of those who were prepared to admit that the mafia existed in places like Calabria and Sicily were convinced that it was a symptom of backwardness. At the time, it was not the problem of organised crime that dominated public discussion of southern Italy, but the issue of poverty. In the South average income stood at about half of levels in the North. In 1951, a government inquiry found that 869,000 Italian families had so little money that they

never

ate sugar or meat; 744,000 of those families lived in the South. If anyone thought about the mafias at all, they thought of them mostly as the result of poverty, and of a primitive peasant milieu characterised by superstition and isolated episodes of bestial violence. In the end, the story of the Monster of Presinaci raised few eyebrows.