Blood Brotherhoods (58 page)

Read Blood Brotherhoods Online

Authors: John Dickie

The conclusion is unavoidable: a magistrate who was a scourge of the mafia in the early 1930s was, by the mid-1940s, an enthusiastic mouthpiece for mystifications that could easily have been voiced by the mafia’s slyest advocates. Once Giuseppe Guido Lo Schiavo had been scornful about the way ‘literature and drama glorified the figure of the

mafioso

’. Now he was himself writing fiction that did precisely that.

But why? What caused Lo Schiavo to upend his views so shamelessly?

Lo Schiavo was a conservative whose political sympathies had made him a supporter of Mussolini’s regime in the 1920s and 1930s. After the Liberation, his conservatism turned him into a friend of the most murderous criminals on the island. The magistrate-novelist’s bizarre rewriting of the mafia records in

Local Prosecutor’s Office

testified to an unspoken and profoundly cynical belief: better the mafia than the Communists. This simple axiom was enough to drive Lo Schiavo to forget his own hard-won knowledge

about Sicily’s ‘criminal system’, and to relinquish the faith in the rule of law that was the grounding ethos of his calling as a magistrate.

Turi Passalacqua, the heroic bandit chieftain of

In the Name of the Law

, was laughably unrealistic. But, in a peculiarly Sicilian paradox, he was also horribly true to life.

In the Name of the Law

may have been a cinematic fantasy, but it nonetheless glorified a very real deal between the mafia and the state in the founding years of the Italian Republic.

Sicily is a land of strange alliances: between the landed aristocracy and gangland in the Separatist movement, for example. And once Separatism had gone into decline, the political and criminal pressures of 1946–8 created a still stranger convergence of interests: between conservatives, the mafia and the police. It is that alliance that is celebrated by

In the Name of the Law

, through the fictional figure of mafia boss Turi Passalacqua, sermonising from the saddle of his thoroughbred white mare.

In 1946, the police and

Carabinieri

were warning the government in Rome that they would need high-level support to defeat the mafia, because the mafia itself had so many friends among the Sicilian elite—friends it helped at election time by hustling votes. But these warnings were ignored. It may have been that conservative politicians in Rome were daunted by the prospect of taking on the ruling class of an island whose loyalty to Italy was questionable, but whose conservatism was beyond doubt. Or more cynically still, they may have reasoned that the mafia’s ground-level terror campaign against the left-wing peasant movement was actually rather useful. So they told the police and

Carabinieri

in Sicily to forget the mafia (to forget the real cause of the crime emergency, in other words) and put the fight against banditry at the top of their agenda.

The police knew that to fight banditry they would need help—help from

mafiosi

prepared to supply inside information on the movement of the bands. For their part,

mafiosi

appreciated that farming bandits was not a long-term business. So when outlaws outlived their usefulness,

mafiosi

would betray them to the law in order to win friends in high places. Thus was the old tradition of co-managing crime revived in the Republican era.

Through numerous occult channels, the help from the mafia that the police needed was soon forthcoming. In the latter months of 1946, the bandits who had made Sicily so lawless since the Allied invasion in 1943 were rapidly eliminated. Until this point, police patrols had ranged across the wilds of western Sicily without ever catching a bandit gang. Now they mysteriously stumbled across their targets and killed or captured them. More frequently outlaw chiefs would be served up already dead. Just like the bandits of

In the Name of the Law

, they would be trussed up and tossed into a dried-up well, or simply shotgunned in the back in a mountain gully.

So at the dawning of Italy’s democracy, the mafia was

exactly

what it had always been. It was

exactly

what the anti-mafia magistrate Giuseppe Guido Lo Schiavo and any number of police and

Carabinieri

had described it as: a secret society of murderous criminals bent on getting rich by illegal means, a force for murder, arson, kidnapping and mayhem.

Yet at the same time, give or take a little literary licence, the mafia was also

exactly

what the novelist Giuseppe Guido Lo Schiavo and the film director Pietro Germi portrayed it as: an auxiliary police force, and a preserver of the political status quo on a troubled island. Without ceasing to be the leaders of a ‘criminal system’, the smartest mafia bosses were dressing up in the costume that conservatives wanted them to wear. Hoisting themselves into the saddles of their imaginary white mares,

mafiosi

were slaughtering bandits who had become politically inconvenient, or cutting down peasant militants who refused to understand the way things worked on Sicily. And of course, most of the mafia’s post-war political murders went unsolved—with the aid of the law.

The Cold War’s first major electoral battle in Italy was the general election of 18 April 1948. One notorious election poster displayed the faces of Spencer Tracy, Rita Hayworth, Clark Gable, Gary Cooper and Tyrone Power, and proclaimed that ‘Hollywood’s stars are lining up against Communism’. But it was predominantly the Marshall Plan—America’s huge programme of economic aid for Italy—that ensured that the Partito Comunista Italiano and its allies were defeated. The PCI remained in opposition in parliament; it would stay there for another half a century. The election’s victors, the Christian Democrats (Democrazia Cristiana, DC), went into government—where they too would stay for the next half a century. Like trenches hacked into tundra, the battle-lines of Cold War Italian politics were now frozen in place.

A few weeks after that epoch-making general election, the most senior law enforcement officer in Sicily reported that, ‘The mafia has never been as powerful and organised as it is today.’ Nobody took any notice.

The Communist Party and its allies were the only ones not prepared to forget. In Rome, they did their best to denounce the Christian Democrat tolerance for the mafia in Sicily. Left-wing MPs pointed out how DC politicians bestowed favours on mafia bosses, and used them as electoral agents. Such protests would continue for the next forty years. But the PCI never had the support to form a government; it was unelectable, and therefore impotent. In June 1949, just a few weeks after

In the Name of the Law

was released in Italian cinemas, Interior Minister Mario Scelba addressed the Senate. Scelba had access to all that the police knew about the mafia in Sicily. But he scoffed at

Communist concerns about organised crime, and gave a homespun lecture about what mafia really meant to Sicilians like him:

If a buxom girl walks past, a Sicilian will tell you that she is a

mafiosa

girl. If a boy is advanced for his age, a Sicilian will tell you that he is

mafioso

. People talk about the mafia flavoured with every possible sauce, and it seems to me that they are exaggerating.

What Scelba meant was that the mafia, or better the typically Sicilian quality known as ‘mafiosity’, was as much a part of the island’s life as

cannoli

and

cassata

—and just as harmless. The world should just forget about this mafia thing, whatever it was, and busy itself with more serious problems.

For over forty years after the establishment of the Republic, Scelba’s party, the DC, provided the mafias with their most reliable political friends. But the DC was by no means a mere mafia front. In fact it was a huge and hybrid political beast. Its supporters included northerners and southerners, cardinals and capitalists, civil servants and shopkeepers, bankers and peasant families whose entire wealth was a little plot of land. All that this heterogeneous electorate had in common was a fear of Communism.

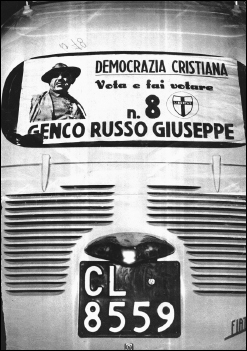

Friends in politics.

Mafioso

Giuseppe Genco Russo stands as a Christian Democrat (DC) candidate (late 1950s).

In Sicily and the South, the DC encountered a class of political leader who had dominated politics since long before Fascism: the grandees. The typical southern grandee was a landowner or lawyer who was often personally

wealthy, but invariably richer still in contacts with the Church and government. Patronage was the method: converting public resources (salaries, contracts, state credit, licences . . . or just help in cutting through the dense undergrowth of regulations) into private booty to be handed out to a train of family and followers. Through patronage, the grandees digested the anonymous structures of government and spun them out into a web of favours.

Mafiosi

were the grandees’ natural allies. The best that can be said of the DC’s relationship with the mafias is that the party was too fragmented and faction-ridden to ever confront and isolate the grandees.

Under Fascism, as on many previous occasions, police and magistrates had painstakingly assembled a composite image of the mafia organisation, the ‘criminal system’. Now, in the era of the Cold War and the Christian Democrats, that picture was broken up and reassembled to compose the Buddha-like features of Turi Passalacqua. Better the mafia than the Communists. Better the Hollywood cowboy fantasy land of

In the Name of the Law

than a serious attempt to understand and tackle the island’s criminal system of which many of the governing party’s key supporters were an integral part.

Thanks to the success of

In the Name of the Law

, and to his prestigious career as a magistrate, Giuseppe Guido Lo Schiavo went on to become Italy’s leading mafia pundit in the 1950s. He never missed an opportunity to restate the same convenient falsehoods that he had first articulated in his novel. More worryingly still, he became a lecturer in law at the

Carabinieri

training school, the chairman of the national board of film censorship, and a Supreme Court judge.

In 1954 Lo Schiavo even wrote a glowing commemoration of the venerable

capomafia

don Calogero Vizzini, who had just passed away peacefully in his home town of Villalba. Vizzini had been a protagonist in every twist and turn of the mafia’s history in the dramatic years following the Liberation. By 1943, when he was proclaimed mayor of Villalba under AMGOT, the then sixty-six-year-old boss had already had a long career as an extortionist, cattle-rustler, black-marketeer and sulphur entrepreneur. In September of the following year, Vizzini’s men caused a national sensation by throwing hand grenades at a Communist leader who had come to Villalba to give a speech. Vizzini was a leader of the Separatist movement. But when Separatism’s star waned, he joined the Christian Democrats. The old man’s grand funeral, in July 1954, was attended by mafia bosses from across the island.

Giuseppe Guido Lo Schiavo took Calogero Vizzini’s death as a chance to reiterate his customary flummery about the mafia. But intriguingly, he also

revealed that, one Sunday in Rome in 1952, the fat old boss had paid a visit to his house. He vividly recalled opening the door to his guest and being struck by a pair of ‘razor-sharp, magnetic’ eyes. The magistrate issued a polite but nervy welcome: ‘

Commendatore

Vizzini, my name is—’