Blood Brotherhoods (32 page)

Read Blood Brotherhoods Online

Authors: John Dickie

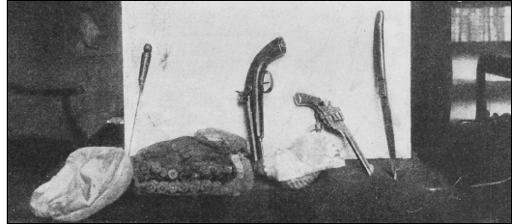

Musolino’s weapons displayed for an avid press.

Positivist criminologists were called on to explain the results of their painstaking physical and psychological examination of Musolino. He had a contradictory mix of symptoms, they explained. There seemed to be no clear aetiology for his criminaloid tendencies. Musolino had suffered a head injury at age six when a flowerpot fell on his head. The accident caused a dent in his skull, and may have given him epilepsy—an obvious delinquent trait. But then again he did not masturbate at all frequently and was very intelligent. Racially speaking, they concluded lamely, he was an exaggeration of the ‘average Calabrian type’.

The most moving speech of the trial came from the lawyer representing the parents of Pietro Ritrovato, the young

Carabiniere

who had died of the horrible injuries inflicted on him by Musolino the morning after the drugged

maccheroni

episode. The old Ritrovato couple had filed a civil suit against the ‘King of Aspromonte’. But they sobbed so much in court that they often had to withdraw. Their lawyer explained that his aim was not to ask for money, but to ‘bring a flower to the memory of a victim who fell in the line of duty’. To that end, he wanted to destroy what he called ‘the legend of Musolino’ by insisting on the one crucial thing that the trial had neglected: Musolino was a member of a criminal association called the picciotteria.

The most squalid testimony came from the mayor of Santo Stefano—the one who had attended Musolino’s sister’s wedding and circulated a petition for a royal pardon. Aurelio Romeo was a chubby man with a sleek black beard who was a major player in one of the two dominant political factions

in Reggio Calabria. In court he affected a flaming moral outrage about how the people of Santo Stefano had been mistreated by brutal and incompetent police. ‘The picciotteria is an invention, an excuse for the police’s weakness,’ he said. Asked about the character of Musolino’s two accomplices who were accused of trying to kill his predecessor as mayor, he said they were just honest, hard-working men.

The trial’s outcome was inevitable: Musolino was found guilty and sentenced to life imprisonment. But equally inevitably Italy had lost a priceless opportunity to draw public attention to the acute criminal emergency in southern Calabria. The early ’ndrangheta would remain shrouded in obscurity and confusion, a little-known curiosity of a little-known region.

Musolino, by contrast, was destined for enduring fame, even as he languished in confinement. Just before the First World War, the English writer Norman Douglas went walking on Aspromonte and heard tale after tale about the brigand’s adventures from his peasant guides.

God alone can tell how many poor people he helped in their distress. And if he met a young girl in the mountains, he would help with her load, and escort her home, right into her father’s house. Ah, if you could have seen him, sir! He was young, with curly blonde hair, and a face like a rose.

Musolino’s hair was actually black. That, at least, the criminologists at the trial had demonstrated beyond doubt.

B

ANKERS AND

M

EN OF

H

ONOUR

O

NE REASON WHY

I

TALY BARELY NOTICED THE RISE OF THE PICCIOTTERIA WAS THAT THE

country had much graver worries. In the late 1880s a building bubble burst, leaving lending institutions with huge liabilities. In 1890 the economy went into recession, piling further pressure on the financial system. Several banks subsequently failed, including two of Italy’s biggest. Another, the Banca Romana, tried to stave off implosion by effectively forging its own money and then using the phoney cash to buy off dozens of politicians. ‘Loans’ from the Banca Romana also helped the King maintain his lavish lifestyle. The Prime Minister was forced to resign in November 1893 when his involvement in the scandal was exposed in parliament.

To many, it seemed as if it was not just the Italian banking system that was about to collapse, but the monarchy and even the state itself. The politician called upon to save the nation was Francesco Crispi, an old warhorse of the Left, a Sicilian who had been one of the heroes of Garibaldi’s expedition back in 1860. Crispi also faced an unprecedented political challenge in the form of the trades unions, the Socialist Party and other organisations recruiting among the peasants and labourers. Crispi responded with repression, proclaiming martial law in some areas of the country and banning the Socialist Party in 1894. Desperate for military glory to reinforce the feeble credibility of the state, Crispi launched a reckless colonial adventure in East Africa. In March 1896, at the battle of Adowa, the Italian army that Crispi had spurred into action was destroyed by a vastly superior Ethiopian force. Crispi resigned soon after the news from Adowa reached Rome.

After Crispi the clampdown on the labour movement was relaxed, but politics continued on its reactionary course. For the next few years conservative politicians would talk openly of putting Italy’s slow and hesitant advance towards democracy into a brusque reverse. In the spring of 1898 a hike in food prices caused rioting. Cannon fire resounded in the streets of Milan as troops mowed down demonstrators. Another new Prime Minister then embarked on a long parliamentary battle to pass legislation restricting press and political freedoms.

In the summer of 1900 a Tuscan anarchist called Gaetano Bresci returned to Italy from his home in Patterson, New Jersey; he was bent on revenge for the cannonades of 1898. On 20 July he set a suitably violent seal on the most turbulent decade in Italy’s short history when he went to Monza and assassinated the King.

By that time, though, Italy was already striding into a very different age. An overhauled banking system, including the newly established Bank of Italy, helped the economy revive. The north-west was industrialising rapidly: in Turin, FIAT started making cars in 1899; in Milan, Pirelli started making car tyres in 1901. Over the next few years Italian cities would fill with noise and light: automobiles, electric trams, department stores, bars, cinemas, and soccer stadia. In politics, reform was the order of the day. More people became literate and thereby earned the right to vote. The Socialist Party, though still small, was strong enough to bargain for concessions in parliament. In 1913, Italy would hold its first general election in which, by law, all adult men were entitled to vote.

A surge in newspaper readerships was another symptom of the new vitality. In 1900, the year that Bresci shot the King, the

Corriere della Sera

had a print run of 75,000 copies. By 1913, it was up to 350,000. So the Italy that followed the King of Aspromonte’s trial in 1902 was a country undergoing a media revolution. Indeed all three of Italy’s Honoured Societies now had to test their aptitude for brutality, networking and misinformation in a much more democratic society—one where public opinion shaped the political decisions that in turn shaped criminal destinies.

The Neapolitan camorra would not survive the challenge.

But in the case of the Sicilian mafia, the new media era made no more impact than the puff of a photographer’s flash powder: it illuminated a crepuscular landscape of corruption and violence for an instant, and then plunged it back into a darkness deeper than before.

The Sicilian mafia dramas of the early twentieth century all arose from the single most sinister moment of the banking crisis of the early 1890s, a murder that would remain the most notorious of mafia crimes for the best part of the next century. Notorious partly because the victim was one of

Sicily’s outstanding citizens, and partly because the killers got away with it, but mostly because the resultant scandal, known as the Notarbartolo affair, briefly exposed the mafia’s influence in the highest reaches of Sicilian society.

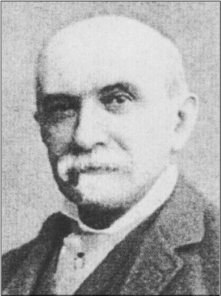

Marquis Emanuele Notarbartolo di San Giovanni fought with Garibaldi in 1860 but he was constitutionally averse to violence. In an age when questions of honour were often settled with swords at sunrise, Notarbartolo was only ever drawn into one duel: it lasted three hours because he only fought defensively. He was a devoted family man who wrote his wife short, tender notes every day of their life together. Notarbartolo was also a public servant of rare dedication. As Mayor of Palermo between 1873 and 1876, he tackled corruption. In 1876 he began a long stint as Director General of the Bank of Sicily, where he made himself unpopular with a policy of tight credit. The reputation for rigour that Notarbartolo earned at the Bank of Sicily would lead directly to his atrocious murder.

Notarbartolo’s fine record found its malevolent shadow in the career of don Raffaele Palizzolo, whom the police would define as ‘the mafia’s patron in the Palermo countryside, especially to the south and east of the city’. Palizzolo’s fiefdom centred on the notorious

borgate

of Villabate and Ciaculli, where he owned and leased land, and where his friends exerted their characteristic control over the citrus fruit groves and coordinated the activities of bandits and cattle rustlers.

Emanuele Notarbartolo, the honest Sicilian banker stabbed to death by the mafia in 1893.

In the 1870s don Raffaele began amassing a fortune by installing himself in town and provincial councils and on the boards of countless charities and quangos (quasi-autonomous non-governmental organisations). When Notarbartolo was mayor of Palermo, he caught Palizzolo palming money from a fund that stockpiled flour for the poor.

Palizzolo was a master of what Italians now call

sottogoverno

—literally ‘under government’—meaning the bartering of shady favours for political influence. Come election time he would tour the area on horseback, flanked by the mafia bosses and their heavies. Indeed the Villabate mafia would often disguise their sect summit

as political meetings in support of their patron. In 1882 Palizzolo was elected to parliament.