Blood Brotherhoods (31 page)

Read Blood Brotherhoods Online

Authors: John Dickie

Stories soon spread that aura further afield. Stories about how, while Musolino was in prison, Saint Joseph came to him in a miraculous vision and revealed the weak points in his cell wall. Stories about how he never stole from anyone, always paid for what he ate, never abused women, and always outwitted the clodhopping

Carabinieri

.

From Aspromonte, the Musolino legend was broadcast by the oral folklore of the entire south. He became a star of the puppet theatre. Children played at being Musolino in the street. Wandering players dressed up as brigands to sing of his adventures or had their poems in praise of him printed on grubby sheets of paper to be sold for coppers. The authorities arrested some of these minstrels, but the cult was now unstoppable. The ‘King of Aspromonte’ himself capitalised on it. Musolino sent a letter to a national newspaper in which he impudently put himself on the side of the ordinary people against authority.

I am a worker, and the son of a worker. I love people who have to sweat in the fields from morning until night so as to produce society’s riches. In fact I envy them, because my misfortune means I cannot make a contribution with my own hands.

The Italian state now found itself losing a propaganda war against the delinquent artisans and peasants of Aspromonte. The whole Musolino affair was turning into what today we would call a PR disaster for the rule of law. Perhaps its most worrying dimension was that the illiterate were not the only people seduced by the myth. Although right-thinking opinion-formers of all political persuasions condemned the popular cult of Musolino as a sign of Italy’s backwardness, books and pamphlets about him still sold in their thousands. In Calabria, only one newspaper dared to suggest that the King of Aspromonte might actually have been guilty of attempting to murder Vincenzo Zoccali. In Naples, where the myth of the noble

camorrista

had such currency, the

Corriere di Napoli

reported fables about the brigand’s supposed acts of generosity without critical comment and came very close to justifying his campaign of retribution.

Musolino only harms his enemies, because he thinks he has a mission and wants to carry it through to the end.

Between the brigand and the law, there was right and wrong on both sides—so went the argument. Accordingly, some press commentators entertained the idea that a fair solution would be to offer Musolino safe passage to the United States.

Eventually the authorities acted on the intelligence that told them Musolino was no lone wolf. Early in 1901, a zealous young police officer, Vincenzo Mangione, was sent to Santo Stefano to implement a more radical strategy than blindly chasing the bandit around the mountain and trying to bribe informants (especially

picciotti

) to betray him.

Mangione compiled a series of highly revealing reports on the picciotteria in Musolino’s home village. Drawing on sources who were mostly disaffected

picciotti

, he describes a ‘genuine criminal institution’, with its own social fund, tribunal, and so on. There were 166 affiliates of the mafia in Santo Stefano. It was founded in the early 1890s by Musolino’s father and uncle, who both now sat on the organisation’s ‘supreme council’. In other words, the evidence collected by Mangione, together with the fact that Musolino was able to rely on a region-wide support network, strongly indicate that the ’ndrangheta has always been a single organisation, and not a rag-bag ensemble of village gangs.

Musolino’s possible motives emerged with a new clarity from Mangione’s research. The bandit was of course an affiliate like his father. Nothing he had done could be separated from his role inside the criminal brotherhood. For example, the attempt on Zoccali’s life that began the Musolino saga was ordered by the picciotteria as punishment because Zoccali had tried to duck out of his duties as a

picciotto

. Musolino was now a roving contract killer for the whole sect.

Most revealingly of all, Mangione learned how the Lads earned favours from ‘respectable people . . . political personalities, lawyers, doctors, and landowners’. The most important of those favours were character references and false witness statements. A more tangible example of the favours that the picciotteria could command stood, ruined and smoke-blackened, at the very entrance of the village. It was the Zoccali family’s house. When Musolino failed to dynamite it, the

picciotti

simply burned it to the ground and then persuaded the town council to deny the Zoccali family a grant to rebuild.

The notables of Santo Stefano were not remotely concerned to keep their friendship with the picciotteria secret. When the King of Aspromonte’s sister Anna got married, the new mayor and his officers, the town councillors, the general practitioners, teachers, municipal guards, and the town band all came to the wedding reception. The mayor chose the occasion to circulate a petition asking the Queen to grant Musolino a pardon.

The outcome of Mangione’s intelligence was a two-pronged strategy to capture Musolino: first, his support network would be attacked; second, the whole picciotteria in Santo Stefano would be prosecuted. Accordingly, there was a series of mass arrests in the spring and summer of 1901. With many of his supporters in custody, Musolino struggled to find a place to hide on his home territory.

On the afternoon of 9 October 1901, in the countryside near Urbino—more than 900 kilometres from Santo Stefano—a young man in a hunting jacket and cyclist’s cap was spotted acting suspiciously by two

Carabinieri

. He fled across a vineyard when they hailed him and then tripped over some wire. He pulled out a revolver but was smothered before he could pull the trigger. ‘Kill me’, he said as the handcuffs went on. He then tried bribery, unsuccessfully. When searched he was found to be carrying a knife, ammunition and a large number of amulets, including a body pouch full of incense, a crucifix, a medallion showing the Sacred Heart, a picture of Saint Joseph, and an image of the Madonna of Polsi. Five days later he was identified as the brigand Giuseppe Musolino.

Musolino was sent for trial in the pretty Tuscan city of Lucca for fear that a Calabrian jury might be too swayed by the myth surrounding him.

His long-delayed encounter with justice was set to be one of the most sensational trials of the age.

But before it could begin, the second arm of the government’s strategy failed. The witnesses Mangione had relied upon to gather evidence about the picciotteria in Santo Stefano were intimidated into retracting their statements. The case never even reached court.

So when national and international correspondents gathered in Lucca to report on the eagerly awaited Musolino trial in the spring of 1902, what they witnessed turned out to be a prolonged exercise in self-harm for the law’s reputation in Italy. The problem was that Musolino’s lawyers objected vociferously every time the prosecution tried to demonstrate that he was a sworn member of a criminal sect. After all, had not the case against this supposed sect in Santo Stefano been thrown out before it reached court? Where was the evidence? In this way, the real context of the Musolino saga was obscured. So a multiple murderer was largely left free to pose as the heroic outlaw that the marionette theatres of southern Italy had made him out to be.

Musolino had spent the time since his capture the previous October writing a verse narrative of his adventures and having his body meticulously measured by positivist criminologists. Over the same period he received countless admiring letters and postcards, particularly from women. They pledged their love, sent him religious tokens and sweets, promised to pray for him and begged for locks of his hair. The judge in Lucca was so concerned about Musolino’s effect on the morals of the town’s womenfolk that he stipulated that only men would be allowed into the hearing. But the stream of fan mail only increased once the trial started. Mysteriously, signed postcard portraits of the King of Aspromonte went on sale near the courtroom. Interviewed by journalists in his cell, Musolino would relish recounting his erotic adventures while he was on the run.

From the outset, Musolino’s lawyers did not contest the fact that he had committed a long trail of murders and attempted murders after escaping from prison. Their defence rested instead on the claim that he was innocent of the crime for which he had been imprisoned in the first place: the attempted murder of Vincenzo Zoccali. The lawyers reasoned that his bloody deeds could be explained, and perhaps even justified, by the conspiracy against him in the Zoccali case.

A visiting French judge was understandably astonished that this argument could even be considered a defence at all; it seemed like evidence of Italy’s ‘moral backwardness’ to him. Musolino did not share the same doubts. When he was called to the dock he told the court that he had concluded his campaign of righteous retaliation now, and would never break the law again if he were allowed to go free. He claimed to be the descendant of a French prince and compared his plight to that of Jesus Christ.

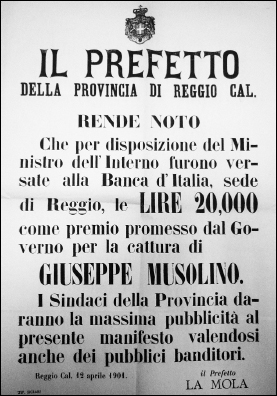

Wanted poster for Giuseppe Musolino, the ‘King of Aspromonte’.

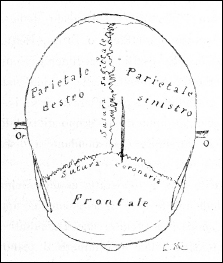

At right, a diagram showing the damage inflicted on Musolino’s skull in infancy by a falling flowerpot.

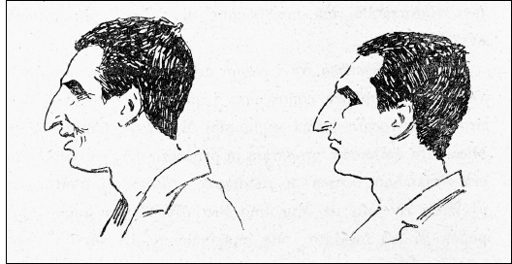

Sketches of Musolino made in court.

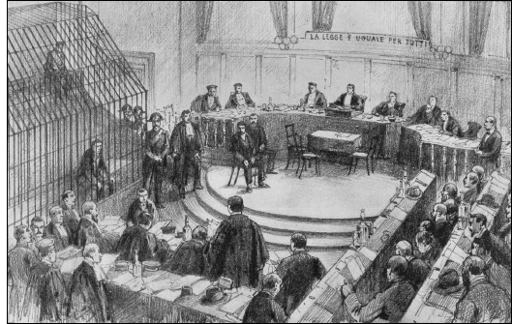

A scene from the Musolino trial in Lucca, 1902. Despite his ferocious deeds, he aroused much public sympathy. ‘Poor Musolino!’ wrote one leading man of letters. ‘I’d like to write a poem that shows how every one of us has a Musolino inside.’

Now and again Musolino did blot the script that portrayed him as a noble desperado: such as when he repeatedly screamed ‘slut!’ at Vincenzo Zoccali’s mother as she came to the witness stand. But that did not prevent many onlookers from sympathising with him. One of Italy’s greatest poets, a sentimental socialist called Giovanni Pascoli, lived in the countryside not far from Lucca and observed the trial with his habitual compassion. ‘Poor Musolino!’ he wrote to a friend. ‘You know, I’d like to write a poem that shows how every one of us has a Musolino inside.’

Many commentators on the trial argued that the underlying problem in the Musolino case was not one lone brigand but the isolation of Calabrian society as a whole. Modern means of communication like the railway would surely bring the light of civilisation to the primitive obscurity of Aspromonte. The sun-weathered peasant witnesses who came up to Lucca for the case made for a spectacle that seemed only to confirm this view. Most of them were Calabrian dialect speakers who had to testify through an interpreter. There was loud laughter on one occasion when, as a witness started to talk, the interpreter turned to the judge and admitted that even he could not understand a word of what was being said. There was probably not a single Grecanico-Italian interpreter available in the whole of Italy.