Blood at the Root: A Racial Cleansing in America (5 page)

Read Blood at the Root: A Racial Cleansing in America Online

Authors: Patrick Phillips

Tags: #NC, #United States, #LA, #KY, #Social Science, #SC, #MS, #VA, #20th Century, #South (AL, #TN, #History, #FL, #GA, #WV), #Discrimination & Race Relations, #State & Local, #AR

C

umming mayor Charlie Harris was among the most moderate voices in the white community, but even he was so anxious after the Plainville “race war” that he gave his wife shooting lessons, in case she needed to defend the house while he was away. Harris’s eight-year-old daughter, Isabella, remembered an urgent telephone call her father made on the morning Grant Smith was horsewhipped, telling his wife, Deasie, that it was time to load the rifle.

In the face of [the] excitement and terror . . . the men downtown heard that a crowd of negroes was assembling near Sawnee Mountain. Their intention presumably was to invade the town, commit robbery, perhaps murder, and intimidate citizens. Father had trained Mother how to shoot . . . and told her to take the gun, loaded but not cocked, to the front porch and have the children around her. If she saw a group of men coming up the grove, she was to fire the gun into the air to frighten them. . . .

[But] while we were sitting there the telephone rang again [and] Leon, my oldest brother, went in to answer it. He came back with the information that no danger threatened us or anybody else. The rumor had started when two colored boys were seen near Sawnee . . . hunting squirrels.

Although Isabella’s mother got that second call before she fired a shot, all over the county whites like her were on edge, watching the horizon with guns at the ready. Such was the level of hysteria, even among upper-class whites like Deasie Harris, that two boys out hunting squirrels—presumably because their families were poor and hungry—could be mistaken for a bloodthirsty black invasion force, intent on “robbery [and] perhaps murder.”

AS THEY WALKED

from the Colored Methodist Campground, the men from the church picnic must have sensed that kind of fear and hysteria rising to a fever pitch all around them. Whatever urgency and determination they’d felt as they set out, when the group rounded a corner and finally arrived downtown, they were stopped in their tracks by the scene on the square. One witness reported that “fully 500 white men came into Cumming from surrounding areas” and “many arms and munitions were [being] sold to citizens preparing to protect their homes.” Another observer said that “old rifles, shotguns ancient and modern, and every variety of pistol possible [was] being loaded and held in readiness.”

Everywhere the men looked, whites were strapping holsters to their belts, stuffing their coat pockets with bullets and shotgun shells, and readying themselves for battle. Facing impossible odds against such a force, they abandoned all hope of saving Reverend Smith, Toney Howell, and the other prisoners in the Cumming jail. Instead they retreated, hoping to at least warn families at the Colored Methodist Campground to stay out of town. “The negroes fled,” according to one reporter, but before they could slip away, they were spotted by a crowd of whites, who gave chase all the way

back to the church barbecue. “A hundred or more white men went to the scene and ordered the negroes to disperse,” said another witness. “They accepted the warning . . . and all negroes venturing into town were run out immediately.”

Having repelled the men from the picnic, and having warned blacks that the town of Cumming was off-limits, the mob now turned its attention back to Grant Smith. The blood-soaked preacher may have slipped from their grasp that morning, but they knew he was still tantalizingly close, somewhere deep inside the Forsyth County Courthouse. According to Charlie Harris’s daughter Isabella, the men refused to disperse even after repeated warnings from Sheriff Reid and Deputy Lummus, and so finally Mayor Harris put down his pen, rose from his desk, and went out to speak with them himself.

“After this mob had come together,” Isabella Harris recalled, “my father addressed them from the courthouse steps.” When they quieted down, the Cumming mayor tried to reason with the crowd and to reassure them that legal justice would soon be done, so there was no need for anyone to go outside the law. “Father begged them,” Isabella said, “to go home, eat their dinners, and get cooled off, change their minds, and not disgrace Forsyth County further.”

Harris clearly hoped to appeal to the men’s better natures, but as he turned back toward the courthouse door, one farmer yelled out over the rest, “We don’t want no dinner, Colonel . . . We wants

nigger

for dinner!”

A roar of approval rose from the crowd, and all Harris could do was shake his head and retreat back inside. With the mob growing louder and bolder, he picked up the telephone and asked the operator to place yet another urgent call to Atlanta. This time Harris told Governor Brown that without protection from the state militia, Grant Smith and the other prisoners were unlikely to survive the night.

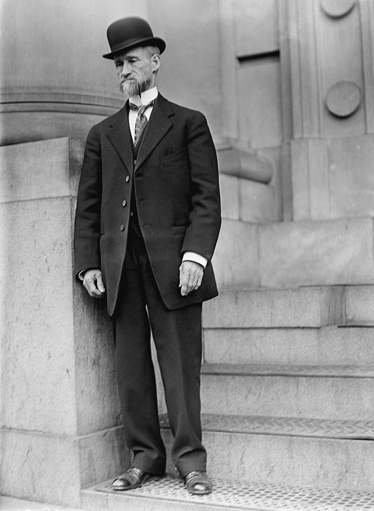

Georgia governor Joseph Mackey Brown in 1912

The man on the receiving end of Harris’s call was Joseph Mackey Brown, who had been elected governor of Georgia in 1908. The son of Joseph E. Brown, Georgia’s governor during the Civil War, Joseph Mackey Brown had been raised in Canton, the seat of Cherokee County, which borders Forsyth, and he still owned a piece of farmland in the foothills. So while “Little Joe” Brown was part of a powerful political dynasty and traveled in the most rarefied circles of Atlanta society, the poor whites of the up-country were deeply familiar to him. He needed no explanation for the tension in Harris’s

voice when the mayor said that a serious case of “lynching fever” had broken out in Forsyth.

Brown knew what a mob of angry white men was capable of, not only from his upbringing in Canton but also from the reports that passed over his desk week after week. Even a brief sample from contemporary newspapers gives a sense of just how often during Brown’s administration Georgia officials confronted the outbreaks of racial terrorism known as “lawlessness”:

February 1, 1910: “Night Riders are said to have killed one negro in Columbia county, and to have burned several homes and churches. To try to bring real facts to the surface would be at the risk of life.”

December 15, 1910: “Terror exists among the negroes . . . of Pike County, due to the whippings of negroes by Night Riders. . . . One of the largest planters in Georgia has appealed to the Governor for troops.”

January 20, 1911: “Owing to the posting of anonymous placards, threatening them with unforeseen dangers, and lynchings, the Negroes of Turner County have left by the hundreds, and are still leaving. This condition of affairs will have serious results at this time of the year for the planters who employ Negroes to work their lands.”

Early in the new century, politicians realized that this rising tide of mob violence posed a serious threat not just to law and order but to the agrarian economy and larger business interests of the state. On August 16th, 1912—less than a month before Grant Smith was attacked—the Georgia legislature had passed an act giving the governor unprecedented new powers to intervene in exactly the

kind of crisis that was spinning out of control on the Cumming square. Whenever the governor has reasonable cause, the new law said, “to apprehend the outbreak of any riot, rout, tumult, insurrection, mob, unlawful assembly, or combination,” he was to order out troops, who would answer not to town and county leaders but to the governor himself.

Critics railed against the measure for weakening local control and “repealing the powers of the mayor and county officials.” But that was precisely the point: to take control away from small-town sheriffs, who often either joined lynch mobs or conspired with their leaders. The new law was meant to protect suspects and—more important to the authors of the bill—to safeguard the supply of cheap black labor that Georgia planters and industrialists had depended on since emancipation.

Once Harris convinced the governor that the mob in Cumming was too large for Reid and his deputies to control, Brown put his new powers to the test for the first time. He called Major I. T. Catron of the Georgia National Guard and ordered two elite companies of the state militia—the Marietta Rifles and the Candler Horse Guards—to muster their men, commandeer cars from private citizens, and head directly to Cumming.

When word spread that the governor was sending troops from Marietta and Gainesville, the men at the front of the mob threw themselves against the locked doors of the courthouse, making one last effort to get their hands on Grant Smith before the militiamen arrived. According to the

Atlanta Georgian

, “a number of the more rabid in the mob [tried] to force an entrance . . . and get the negro held there. However, the deputies, headed by M. G. Lummus, held [them] back.”

AT SOME POINT

during that shoving match, someone in the crowd noticed a dust cloud rising in the distance, and others strained to

hear a low droning sound, rising in pitch as it came closer. As more and more people turned to look, a long line of “high-powered automobiles” came into view, barreling down Dahlonega Street and headed straight for the crowd outside the courthouse.

When the convoy of Model T’s, Internationals, McIntyres, and Acme Roadsters ground to a halt, most people on the square simply gawked in disbelief. In a place where nearly everyone still traveled by horse and buggy, in mule carts, in wagons, or on foot, this was enough to strike even the most bloodthirsty lynchers momentarily speechless. The cavalry had arrived, just as Governor Brown and Mayor Harris had promised, but they hadn’t come on horseback. They rode into town in a gleaming, ticking row of beautiful machines, the likes of which nobody in Forsyth had ever seen.

Fifty-two soldiers of the Candler Horse Guards and the Marietta Rifles spilled out into the street, formed up ranks, clicked the heels of their knee-high black boots, then stood at attention in caped uniforms, shouldering their fifty-two identical Springfield carbines. To the mob of sunburned, overall-clad farmers who had spent the afternoon trying to batter down the courthouse door, the meaning of the spectacle must have been unmistakable. Cumming had been invaded all right, but not by black rebels, and not by crazed black rapists. Instead, a professional army representing the governor and the moneyed interests of the state had come to put everyone in Forsyth, black and white, back in their rightful places.

It was widely reported that although Governor Brown hesitated to intervene in local matters, once he did deploy troops, they would be authorized to take any and all steps necessary. “When soldiers are called upon by the civil authorities,” Brown said, “it is to be assumed that it is soldiers with soldiers’ weapons that are needed.” In a speech before the Georgia legislature, he reiterated that he would use the new law to preserve order, even at the cost of civilian

lives. “The suppression of anarchy is the right and duty of all,” the governor declared, “and there come times when they must shoot it to death just as they shoot down foreign invaders.”

The Marietta Rifles, “Riot Duty Company,” c. 1908

Facing fifty-two “soldiers with soldiers’ weapons” who were authorized to fire at will, the rioters in Cumming quickly realized that defying the governor’s army, as they had defied Mayor Harris all morning, might well end with a bullet to the head. And so, as the sun sank low over Sawnee Mountain, most of the crowd complied with orders to disperse and finally went home to eat their cold suppers, as Harris had been asking them to do since midday. The last, most stubborn members of the mob looked on in disgust as troops formed a “hollow square” around Grant Smith and escorted the preacher down the courthouse steps and across Maple Street, where he joined the five Grice suspects in the Forsyth County Jail.

As the roar of the mob gave way to the sound of sentries marching up and down the empty streets, the prisoners must have realized that—as unfortunate as they were to have been arrested in the first place—they could now count themselves lucky to be alive. After listening to the curses and threats of the lynchers all afternoon, they must have experienced no moment quite so heart-stopping as when, just after dark, Deputy Lummus appeared in

front of their cells with a lantern, swung the heavy iron doors open one by one, and ordered the men to step outside.