Blood at the Root: A Racial Cleansing in America (9 page)

Read Blood at the Root: A Racial Cleansing in America Online

Authors: Patrick Phillips

Tags: #NC, #United States, #LA, #KY, #Social Science, #SC, #MS, #VA, #20th Century, #South (AL, #TN, #History, #FL, #GA, #WV), #Discrimination & Race Relations, #State & Local, #AR

Such scenes were common enough in post-emancipation Forsyth that in 1897 Judge George Gober made a special trip from Atlanta to Cumming in order to try a man named Charley Ward, who stood accused of raping a prominent famer’s fifteen-year-old daughter. “Gober gave him the limit allowed by law, twenty years,” said the

Macon Telegraph

, and “a speedy trial was had to prevent a case of lynching, which had been planned to take place Christmas day.”

These earlier lynchings and near lynchings suggest that rather than yielding to a sudden, irresistible passion—as lynchings were usually portrayed—the men pounding on the door of the Cumming jail on Tuesday, September 10th, 1912, were taking part in a time-honored ritual. Many would have heard tales of past lynchings from their fathers and grandfathers, and when Rob Edwards was arrested on suspicion of rape, they saw their chance to finally join that grand tradition: to show that they, too, were men of honor, and no less committed to the defense of white womanhood.

IF REID’S SOLUTION

to the problem of a lynch mob was to pretend it did not exist, his strategy worked, at least in the short term. According to one witness, Lummus “stood his ground bravely against the assault and was warned to get back and save himself.” Hearing the shouts

and curses of hundreds of men who now viewed him as nothing but an obstacle to be overcome or passed through, Lummus reportedly “locked the doors of the jail and put the heavy bars in place.” He positioned himself between his prisoner and the mob, and through the barred door he pleaded with mob leaders to settle down, go back home, and let the Blue Ridge Circuit court take care of Big Rob Edwards.

But outside a murmur was passing through the crowd, and soon a man who’d been sent to a nearby blacksmith’s shop was ushered to the front—a long crowbar clenched in one hand, a sledgehammer in the other. As the front door creaked and splintered under the first blow of the sledge, Lummus drew his pistol, spread his arms, and backed toward the row of cells. At the second blow, daylight streamed through a gash in the wooden planks, and just like that, the

Georgian

said, “the mob came on.” A reporter told how

farmers known to all the countryside were in front of the band, which advanced in broad daylight, without a mask, without the slightest fear of what the future might bring. The barred doors . . . gave way under a few heavy blows and the leaders rushed in, followed by as many men as could crowd into the corridors.

Having risked his life to protect Edwards, Lummus was shoved aside as dozens of men stomped over the wreckage of the door and headed straight for the row of cells at the rear of the building. Inside one of them stood Big Rob Edwards, his back against the red brick wall.

WHEN LEADERS OF

the mob emerged from the jail with a black man, they were cheered by thousands of whites who had rushed into town in hopes of witnessing exactly such a spectacle. “Out into the sunshine came the negro,” said the

Georgian

, “gray in his terror, his eyes rolling in abject fear.” Edwards “muttered prayers and supplications to the mob,” one reporter noted,

but these were soon drowned in the rain of blows which fell upon him. A rope was brought from a nearby store and a noose dropped around the negro’s neck. The mob was fighting for a chance to get at its victim, and only the certainty of wounding or killing a friend kept the drawn pistols silent.

Across the street and up to the public square hurried the mob, its victim at the fore. The negro had lost his feet by this time and was being dragged by the rope, his body bumping over the stones. At the corner of the square a telephone post and its cross-arm offered a convenient gallows. The end of the rope was tossed over the arm, a dozen hands grasped it and the negro, perhaps already dead, was drawn high into the air.

After a week of frustration, the abduction and killing took only minutes. There is no way to know whether Edwards died from a gunshot wound, a crowbar to the skull, or strangulation as he was dragged around the Cumming square—but when his limp, blood-slick body finally rose into view high over the crowd, thousands of people joined in. As they loaded their weapons and took aim, rebel yells and howls of celebration rose from the crowd. “Pistols and rifles cracked,” a witness said, “and the corpse was mangled into something hardly resembling a human form.”

The

Marietta Journal

claimed that “as soon as the guns of those composing the mob were empty the crowd quietly dispersed and returned to their work,” but other accounts suggest that many in the crowd looked up at Edwards’s corpse and felt not satisfied but more hungry than ever. They had finally killed one of the accused rapists, and now their thoughts turned to the five young men arrested in connection with the Grice assault. Those prisoners were only forty miles south in Marietta, and even as people stood gawking at Edwards’s body, leaders of the mob waved men into cars bound

for the Marietta jail—where they hoped to do to Grant Smith and Toney Howell exactly what they’d just done to Rob Edwards.

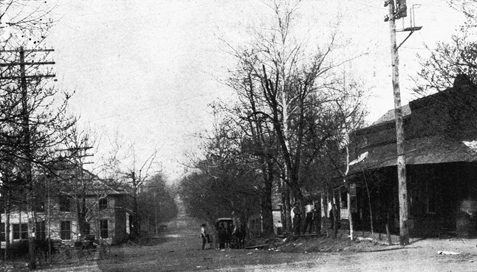

Charlie Hale, Lawrenceville, Georgia, 1911. Hale died twenty miles south of Cumming and, like Rob Edwards, was abducted from the local jail and hung from a telephone pole on the town square

.

SHERIFF REID EMERGED

only once “the excitement” was over—when he could claim to have had no idea that Rob Edwards wasn’t still asleep in his cell. Having left Lummus in command, Reid could now shake his head and tell reporters he didn’t know who’d

broken down the jailhouse door, who’d fired the first shot, or how exactly his young deputy had failed to protect the prisoner. After learning that some of the lynchers were speeding out of town, Reid made a phone call to Judge Newt Morris in Marietta, warning him that “the mountaineers were threatening to come . . . and storm the jail there.” In response, Morris ordered Cobb County Sheriff J. H. Kincaid to move the Grice prisoners yet again, this time to the one jail in the area that could stop any mob: Atlanta’s Fulton Tower, where the night before Ernest Knox had been sent for safekeeping.

In the end, the cars from Forsyth turned around just outside Marietta, when a local farmer told them that the Grice prisoners had already been transferred to the Tower. Pulling back into the Cumming square after dark, they rolled slowly past the splintered door frame that just a few hours before had been ripped to pieces with sledges and crowbars. On a corner near the courthouse, they passed the mutilated, almost unrecognizable corpse of Rob Edwards, still hanging from the yardarm of a telephone pole. A reporter for the

Georgian

took a last glance at the scene before heading back south to Atlanta. “[Edwards’s] body swings there to this hour,” he wrote, “riddled with bullets, dangling in the wind as a warning to frightened negroes, who are hurrying from the town.”

As the last of the crowd drifted toward home, Reid ordered Lummus to cut Edwards down and drag him to the lawn of the Forsyth County Courthouse. There, the

North Georgian

said, “his body lay [out] all night, without a guard, and it was not touched.” The next morning, county coroner W. R. Barnett knelt over the stiff corpse, examining the lacerations on Edwards’s swollen neck, the hundreds of holes from bullets and buckshot, and the deep impact wounds in his skull. Barnett’s report concluded that the twenty-four-year-old black man had suffered multiple gunshots and blunt trauma to the head. Despite eyewitness accounts saying that “farmers known to all the countryside” had come “unmasked [and] threw

off all attempt at concealment,” Barnett wrote that Rob Edwards died at the hands of “parties unknown.”

West Canton Street, Cumming, c. 1912

In the days that followed, Georgia newspapers were quick to declare that the bloody ritual had been an end, not a beginning, to Forsyth’s “race trouble.” “The provocation of the people of Forsyth was great,” said the

Cherokee Advance

, “and they simply did what Anglo-Saxons have done North, South, East and West . . . where negroes have outraged white women. They formed a mob and took the law into their own hands.”

The

Atlanta Journal

agreed that, as gruesome as the killing was, whites had now exhausted their rage and “no further trouble was expected” at Cumming. An editorial in the

Gainesville Times

went further, congratulating the white mobs of Forsyth for having done no worse, and for having lynched no more. “Two criminal assaults in one week wrought up the people to a high pitch,” the editors said, “[and] they controlled themselves with remarkable self-restraint.”

W

hile the public whipping of Grant Smith had put the entire black community on edge, the sight of Rob Edwards’s corpse hanging over the public square sent whole wagon trains of refugees out onto the roads of the county; they fled south toward Atlanta, east toward Gainesville, and west toward Canton. African Americans in Forsyth knew that nothing they said or did was likely to convince Bill Reid to pursue those who had murdered Rob Edwards. And if anyone still held out hope that, in the wake of the killing, whites might leave their black neighbors in peace, they learned otherwise the next morning, when tensions rose over the burning of a building near Cumming.

When they heard that the storehouse of a white man named Will Buice had mysteriously caught fire in the night, whites concluded that it was the work of black arsonists, retaliating for the lynching. The

Georgian

reported that “the clouds of race war which have hung over Forsyth . . . threaten to break into a storm of bloodshed today.” The fire was taken as proof that, just like in Plainville, Cumming was now on the brink of a black insurrection. “Rumors that the negroes . . . are rising and arming themselves have led almost

to a panic among the women of the little town,” one observer wrote, adding that

even the conservative men fear that the lynching of yesterday and the burning of a store today are merely the first movements in a race war which may sweep the county and bring death to many. Citizens are arming for trouble.

But despite all the rumors, most black residents were too busy trying to protect their families to think about retaliation. Like African Americans all over the Jim Crow South, they understood that even the mildest forms of resistance or the faintest hint of protest could trigger a new wave of white violence. Many would have heard about the black woman in Okemah, Oklahoma, who, in 1911, had been killed for no crime other than defending her fifteen-year-old son against a lynch mob. Newspapers reported that when Laura Nelson confronted the white men who had accused her boy of stealing, Nelson was dragged from her house and repeatedly raped before she and the son she’d tried to protect were hanged side by side from a bridge over the Canadian River.

If anyone in Forsyth’s black community thought of publicly naming the leaders of the mob that had killed Edwards, they would have understood the terrible risk. Only a few years later, in 1918, a pregnant woman named Mary Turner would be killed in Lowndes County, Georgia, for having openly grieved for her husband, Hayes. When she threatened to swear out warrants against the men who had abducted and lynched him, the response was swift and savage, even by the standards of Jim Crow Georgia. According to historian Philip Dray, “before a crowd that included women and children, Mary was stripped, hung upside down by the ankles, soaked with gasoline, and roasted to death. In the midst of this torment, a white man opened her swollen belly with

a hunting knife and her infant fell to the ground, gave a cry, and was stomped to death.”