Blood at the Root: A Racial Cleansing in America (14 page)

Read Blood at the Root: A Racial Cleansing in America Online

Authors: Patrick Phillips

Tags: #NC, #United States, #LA, #KY, #Social Science, #SC, #MS, #VA, #20th Century, #South (AL, #TN, #History, #FL, #GA, #WV), #Discrimination & Race Relations, #State & Local, #AR

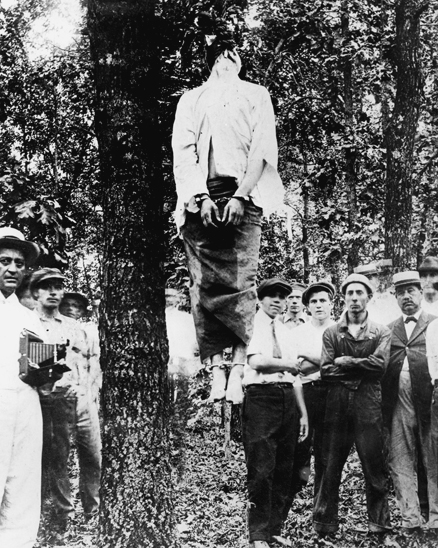

The lynching of Leo Frank outside Marietta, Georgia, 1915. Judge Newton A. Morris (far right, in bow tie and straw hat) stands among the crowd of spectators

.

At a nod from Major Catron, Judge Morris passed through a military checkpoint in Bill Reid’s pasture. Then he and the attorneys followed a soldier past rows of glowing campfires, until they

reached the little cluster of tents where Jane Daniel and the other prisoners were trying, and no doubt failing, to get some rest.

After a brief fireside conversation with Jane and the accused men, Morris and the lawyers appeared once more at the checkpoint and were escorted back to Cumming by Sheriff Reid. What sort of bargain they had come to offer—and what they’d asked in return—was not reported. But the next day’s evening papers shocked readers with news that the sister of one of the accused men had suddenly, and supposedly of her own accord, “turned State’s evidence” and agreed to testify for the prosecution. For reasons no one could, or would, explain, the night had wrought a sudden change in young Jane Daniel.

AFTER BREAKFAST ON

the morning of Thursday, October 3rd, the soldiers struck their tents and readied the prisoners for the last mile of the march, through the dusty streets of Cumming. The little town, according to one observer, was “crowded as never before in its history” as people all over north Georgia were drawn by the excitement. Surrounded by military guards as they walked up Castleberry Road, the prisoners faced the jeers and howls of “mountaineers [who had] been gathering weapons,” according to one reporter, “and making threats that the accused negroes would not be permitted to reach the jail.”

To protect them, the governor had ordered out an overwhelming show of military force and armed the guardsmen to the teeth. In addition to the Springfield carbines slung over their shoulders, the

Georgian

reported, the soldiers of the Fifth Regiment were “ordered to discard the usual revolver and equip themselves with the new Army derringer pistols . . . which automatically discharges eleven heavy bullets and can be reloaded in a second.” Governor Brown’s declaration of martial law had even concluded with a steely warning to people crowding into town for the trials: “While

it is the desire of the authorities to exercise the powers of martial law mildly, it must not be supposed that they will not be vigorously and firmly enforced.” When Judge Morris was asked about the potential for trouble while walking towards the courthouse, he paused just long enough to remind a reporter that the troops were authorized to fire at will: “any disorder,” he said, “[will] have serious, if not fatal, consequences.”

Sheriff Reid had summoned eighty-four men for jury duty, so when Morris banged his gavel and opened

State of Georgia v. Ernest Knox

, jury selection was the first order of business. By eleven a.m., fifty-six “talesmen” had been questioned, and twelve jurors agreed upon. Five were struck for being over sixty; as to the other thirty-nine who were disqualified? An Atlanta reporter with a gift for understatement said that “their minds were not clearly unbiased as between the prosecution and defense.”

The judge empaneled a jury of twelve white men, eleven of them employed as farmers and the twelfth as “a watchman at the local mill.” Among these otherwise unremarkable “people of the county” were two jurors—E. S. Garrett and William Hammond—who would join the Sawnee Klavern of the Ku Klux Klan in the early 1920s. Guarding the door was Sheriff Reid, who would stand beside them as a Klansman, dressed in his own white robe and hood. Seated among the lawyers were two of Leo Frank’s future lynchers, Fred Morris and Howell Brooke. And at the very center of the courtroom, directing the whole affair, was Judge Newton A. Morris.

No doubt conscious of all the reporters in attendance, the judge called the murmuring spectators to order, then announced in a booming voice that he would “expedite the trial in every manner possible” and at the same time ensure that the proceedings were “fair and impartial.” The purpose of the entire process, Morris said—with a grave and imperious glance around the room—was to “uphold the majesty of the law.”

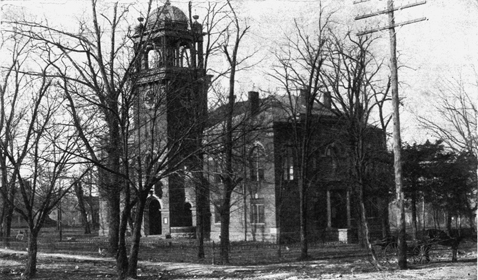

The Cumming Courthouse, c. 1912

If Morris’s speech gave even a glimmer of hope to Ernest Knox, it must have faded when the prosecution called the day’s first witness: Mr. L. A. “Bud” Crow. Mae’s father was listed as the official prosecutor of the case, and he struck a pitiful figure as he sat, hat in hand, and spoke of his beloved daughter; of the morning he’d first looked upon her bloody body; of the two weeks his wife, Azzie, had spent praying at Mae’s bedside; and of her recent death and burial, at a funeral attended by many people present in the courtroom. Bud Crow “was compelled to repeat the pathetic story of his daughter’s shameful handling,” a reporter wrote, “and the recital stirred the depths of [even] the most hardened onlookers.”

The two witnesses who followed—Dr. George Brice and Dr. John Hockenhull—made the prosecution’s strategy clear. They would ask witness after witness to describe Mae’s injuries and stoke the same sense of horror and outrage that had led to the lynching of Rob Edwards. The image of Mae Crow’s broken, defiled body was enough, they knew, to make a conviction of Ernest Knox all but inevitable.

AFTER THE DEAD

girl’s father brought many in the crowd to tears, and after the doctors shocked listeners with their accounts of Mae’s fractured skull and lacerated throat, the next witness was Ed Collins, a black farmer from Oscarville, who was among the prisoners brought north from the Fulton Tower. There is no telling what Collins’s wife, Julia, knew or didn’t know during the time her husband was jailed, but if she had dared to venture into Cumming for the trial, it would have been the first time she laid eyes on him since mid-September. For at least two days during their separation, Collins was mistakenly identified by reporters as the man whose body had hung from a telephone pole on the Cumming square. When Collins rose and walked toward the witness stand, the reason for the mistake was clear to everyone: just like “Big Rob” Edwards, Ed Collins was a tall and powerfully built young black man.

Collins was called not by the defense but the prosecution, because the story he told implicated Knox and Daniel through circumstantial evidence. He said that on the day of Mae Crow’s disappearance, Knox and Edwards came to his house in Oscarville and stayed until about ten p.m. Most importantly for the state’s case, Collins testified that “they borrowed a lantern . . . and [said] they were going in the direction of the Crow home, which was about two miles away.”

Thus began the prosecution’s attempt to prove allegations that had been racing from storefront to storefront all month. After Ernest Knox met Mae Crow on Durand Road and beat her over the head with a rock, the story went, he dragged Crow’s unconscious body into the woods, then went to find Rob Edwards and his cousins Jane and Oscar, and led them back to the scene. There, all three men were said to have spent the night repeatedly raping Crow.

This narrative justified the prosecution of Daniel as well as Knox, explained the arrests of Ed Collins and Jane Daniel, and,

most importantly, redefined the lynching of Rob Edwards as a just punishment for a heinous crime. As a prosecutor turned his back to Ed Collins, he told the jury that Knox, Daniel, and Edwards had borrowed Collins’s lantern not because they had stayed later than intended, not because it was dark, and not because they had a long walk home. Instead, the jury heard, it was because a beautiful white girl was lying out there unconscious in the woods, and they needed a light to find her.

Ed Collins, October 1912

If anyone in the courtroom had doubts, the prosecution’s next witness presented what seemed like irrefutable evidence: a confession that came from Ernest Knox’s own lips. Whatever else he said on the witness stand, it’s clear that Marvin Bell left out the fact that Knox had confessed while in the midst of a mock lynching. Bell reiterated what was now the widely accepted story: that on Sunday, September 8th, Ernest Knox had met Mae Crow while she was walking on the road between her parents’ and her aunt’s house, bashed in her skull in the throes of a sexual rage, left her unconscious body in the woods, then returned with Edwards and his cousins, Jane and Oscar. Bell said that Jane was forced to come

along by her brother, her cousin, and her husband—to “hold the lantern” while the three men took turns raping Crow.

By the time Marvin Bell sat down, most whites in the gallery were nodding in agreement with a patently unconvincing story, which the next day’s

Constitution

deemed “one of the most revolting rape cases in the annals of the state.” As Ernest Knox sat stone still beside his team of reluctant defense attorneys, Newt Morris rose from the bench, tapped his gavel, and announced a midday adjournment.

S

heriff Reid took the recess as an opportunity to once more strike the pose of a brave country lawman. At one point, as he threaded his way out through the dense crowd surrounding the courthouse, he leaned into a circle of journalists and whispered that he’d just received an urgent message from Atlanta. The sheriff warned, one reporter said, that “1,000 rounds of ammunition are en-route to Cumming . . . [though] he declined to give the source of his information.”

If the writer sounds skeptical about the sheriff’s tale, perhaps it is because there are no other references to such a shipment, and no evidence that any such threat ever existed. But that moment gives a clear picture of Reid on the day of the trial: desperately playing to the crowd, trying to somehow keep himself center stage—particularly as photographers focused their cameras on the dashing soldiers of the Fulton Blues. When a reporter asked Reid to elaborate on the story, the sheriff confessed that “he [did] not believe this report to be true,” but hurried to add that he was “making arrangements to intercept any such shipment should it be en-route.”

No matter how broadly Reid played his role as guardian of the county, Judge Morris was the real ringmaster on the day of the

trials, and Catron’s soldiers were stars of the show. One reporter noted that while there were “enough determined men in Cumming today . . . to overpower a sheriff’s posse and hang the accused men to the nearest tree,” those “who felt that the two rapists deserved immediate death [were stopped by] the businesslike look of the men behind the army rifles.”

As hundreds of whites milled around the courthouse and tried to catch a glimpse of the prisoners inside, the signs of martial law were everywhere. According to the

Constitution

, the military guard kept “at a safe distance a crowd that would have otherwise made short work of the accused negroes.” The

Georgian

said that “Major Catron has 24 men stationed in the court room, while squads are on duty in the corridors, on the stairways, in the court house yard and around the fence surrounding the building. Other soldiers are patrolling the streets of the town, while a reserve force is held in readiness to move at a moment’s notice, should there be any demonstration.” The article was accompanied by a photograph showing a guardsman, rifle at the ready, perched on a ledge of the courthouse wall, lest anyone attempt to take a shot through the window.