Batavia (60 page)

Authors: Peter Fitzsimons

A few days later, at her insistence, they were even joined beneath the waves by the 60-year-old Henrietta Drake-Brockman

! Only upon surfacing did she agree with Hugh that the site of the atrocities wasn’t Goss Island after all, though she could legitimately take a bow for having moved the whole focus of the search 30 miles north from where the wreck was long presumed to be.

Of all the things drawn up from the floor of the ocean among the

Batavia

’s debris on this campaign – Edwards’s first to discover her secrets – was a bronze object that initially looked like a bell. Yet the Latin inscription around its rim made it obvious that the opening should be placed uppermost, at which point they realised what it was.

‘An apothecary’s mortar!’ cried one of the diving party.

Hugh Edwards knew instantly to whom it had almost certainly belonged – the only apothecary on the ship, Jeronimus.

And what did the inscription say?

Click Here

Love conquers all.

On this same expedition, they discovered sword-chopped skeletons in shallow graves on Beacon Island, proving beyond any doubt that this tiny patch of land was

indeed the site of Batavia’s Graveyard

.

Dave Johnson had long known about the existence of those graves. ‘You can tell where the skeletons are,’ he explained to his startled companions. ‘I find them when I am burying rubbish.

The soil has a characteristic dark greasiness

.’

Research on the site has gone on for the last 50 years, and new discoveries are still being made. In 1999, six bodies were unearthed from just the one pit by the Western Australian Museum – Maritime. There were three adults, a teenage lad, a small child and a baby aged eight to nine months.

The expert view was that a lack of trauma marks on the bones suggested the victims’ throats had been cut, or they were strangled in their sleep, before being dumped in the prepared grave that could have been hidden under a tent temporarily ruled and guarded by mutiny leader Jeronimus.

Surely, 370 years on, the handiwork of poor Andries de Vries, following the design of Jeronimus to be rid of all those in the hospital tent, had finally been discovered.

And what, though, of the wreck itself? While a good chunk of it is now in the Western Australian Museum – Maritime, bits and pieces still lie forlorn, cradled in a grave of the

Batavia

’s own making, while endless rollers crash overhead onto the very reef she impaled herself on, one night so long ago. Somehow, of all the images that I have come across in the course of researching and writing this book, of all the poignant scenes I have described – many of them violent and distressing – the one that comes back to me the most is what I saw from a plane right above the wreck site.

Stunningly, even nearly 400 years on and from a hundred metres in the air, you can still see clearly the exact imprint of the shape of the ship, a pale shadow on the ramparts of the reef in the bluey-greenness all around. It is an imprint of a once mighty ship, built for mighty things by some of the finest marine craftsmen in all of the world, only to be done under, torn asunder by the failings of a few men. That exact shape on the reef is like a photographic negative, the reverse image of something vibrant and fantastic, which gives you a strong clue of what once was. In how many other spots on earth do we see the evidence, still, of a major man-made mishap of four centuries ago? Personally, I can count them on the fingers of one finger: the

Batavia

.

Nature can’t quite obliterate the image of that ship from the planet, any more than mankind can collectively forget what happened – for the story, and the impact of the story, is simply too strong.

Vale

, the

Batavia

, and all who sailed upon her, even Jeronimus.

The coats of arms of the Dutch East India Company (left) and the city of Batavia. The VOC coat of arms depicts a trophy of armoury, nautical instruments, flags and man-of-war supported by Neptune and Providentia (holding a mirror) with the VOC cipher at the top. The Batavia coat of arms shows a sword crowned with a laurel wreath and lions on both sides armed with seven arrows and a sword, the whole surrounded by two crossed palm branches.

(Rijksmuseum)

The flag of the VOC featuring the initial ‘A’ for Amsterdam together with the VOC cipher adopted by the

Heeren XVII

on 28 February 1603 (flying from the replica ship

Amsterdam

).

(Photolibrary)

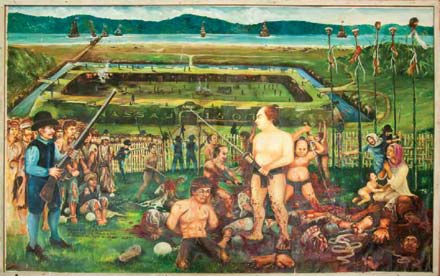

In what was to become known as the Bandanese Massacre, Governor-General Coen mercilessly ordered six of his Japanese samurai to behead and quarter 44 chiefs in front of family and friends before mounting their heads on pikes.

(Doug Meikle, Dreaming Track Images)

Protected by 24-feet-high stone walls and a series of canals, the nascent settlement of Batavia quickly grew into the political, financial and military nerve centre of the VOC’s entire East Indies spice-trade operation.

(Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales)

Looming over the harbour, the heavily fortified citadel of Batavia served to remind both friend and foe of the supreme might of the VOC in the Dutch East Indies.

(Rijksmuseum)

Responsible for establishing the VOC’s seventeenth-century domination of the Spice Islands, company man Jan Pieterszoon Coen served two terms as Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies.

(Rijksmuseum)

Hendrick Brouwer, brother-in-law of Commandeur Francisco Pelsaert, pioneered the Brouwer Route, which took advantage of the Roaring Forties and reduced the voyage from Amsterdam to Batavia by six months.

(Rijksmuseum)