Batavia (56 page)

Authors: Peter Fitzsimons

Pelsaert is satisfied that all justice for Jeronimus rests now in the hands of the good Lord. And, now that Jeronimus is dead, the others follow in quick succession, each man wild-eyed as he nears his end, trying desperately to find a way to make good on earth in preparation for the hereafter.

As the rope is placed around his own neck, the seemingly bloodless Mattys Beer awakes from his dead faint and confesses to the

Predikant

that, beyond the murders he has already confessed to, he also ended the lives of four other men, as well as a boy, whom he killed by cutting their throats in the presence of Jeronimus one night. He requests that the

Predikant

pray for him on account of his many sins.

And yet, when the

Predikant

asks Mattys Beer for the names of his victims, the young man is at a complete loss. When the killings were in full swing, names did not matter. And so Beer is himself soon in full swing, his body jerking as the wind whistles and the remaining murderers still look on in full horror of what awaits them.

Andries Jonas is next. With the noose around his neck, he begins to weep and recounts how, one night when a lot of killing was going on, an ill boy came creeping into the tent he shared with Jacop Pietersz, pleading for safe shelter. And on that terrible night, when another of the Mutineers saw what had occurred, he said to Andries, with a wink, ‘Andries, you must help to put the boy out of the way of all this . . .’

‘And so,’ the weeping Andries finishes, the words tumbling out of him as if they have been trapped for so long and can finally escape, ‘I went outside, got my knife, then went back in, grabbed the sick boy by the hair out of the tent, and then I . . . then I . . . cut his throat and killed him.

Ik doodde hem.

I killed him.’

Andries, too, does not know the lad’s name. There is nothing more to say, and, within a minute of shaking his head that he killed someone that he cannot even name, Andries, too, is in the hereafter, his body swinging beside those of Jeronimus and Mattys.

The one who shows a little fight is Allert Jansz. Like his so-called

Kapitein-Generaal

, this one makes no plea for mercy, nor utters a single word of regret. His only pronouncement is to turn towards Pelsaert and tell him, with a gleam in his eye, to watch well upon his return journey towards Batavia on the

Sardam

– aye, watch well – because

there are many more Mutineers still alive

than swinging here . . . though he does not wish to be called an informer after his death.

Pelsaert nods, though whether it is an acknowledgement to Jansz that he has heard him or a signal to the executioners to get on with it is not certain – but, one way or another, within 30 seconds Jansz’s body is also twisting in the wind.

And so it goes. Next, Lenart van Os, Rutger Fredericxsz and Jan Hendricxsz are hanged, the last nearly toppling the gallows as his full massive weight comes hard down upon it.

Finally, just one man is left: the youngest, Jan Pelgrom, who is still only 18 years old.

Screaming, weeping, unable to stand, Pelgrom pleads for his life, begging Pelsaert to display mercy, a mercy that Pelgrom never remotely showed to his many victims himself, though this point seems to escape him.

. . .

Is enough not finally enough? Have these last months not seen enough bloodshed, enough screaming, enough agony? Something the boy says reaches Pelsaert.

‘

Moeder, moeder,

my mother, my mother! What of

mijn moeder

?’ the lad keeps weeping pathetically, even as it becomes obvious that the wretch has soiled his dungarees.

Is he not right, though? What of his mother? Somewhere back in the Dutch Republic, that good woman will anxiously be awaiting news of her lad, hoping that all is going well for the child she has borne, suckled, weaned and nurtured thereafter. Could Pelsaert really, as a conscious decision, kill him outright? Especially since it really was not that long ago that this ’un was at his mother’s breast?

Certainly, Pelgrom is beyond vile, hideous in his actions, and at least as bad as most of the rest who have already been executed. But he is only

18

years old. A mere pup in a den of wolves. Is it actually fair to condemn the lad outright because, as a matter of purest survival, he tried to become a wolf too? How many in the same situation would not have done the same?

But

how

can he let this otherwise death-deserving delinquent live? Taking him back to Batavia is clearly out of the question. With a confession such as his, he would be dead within days once the Dutch judiciary got hold of him . . .

But, maybe, maybe, there is another way out.

Quite uncharacteristically, Pelsaert takes an impulsive decision. ‘Let him go,’ he says resignedly. ‘Clean him up and take him back to the skiff.’

2 October 1629, Batavia’s Graveyard

On Batavia’s Graveyard, they gather on the shore in silence as the boats return from Seals’ Island. All eyes scan them as they near. Is it at last true? Is he . . .

dead

?

For many, it simply does not seem possible that such a man as Jeronimus could be executed by anything less than a flaming stake through his heart, and perhaps with that in mind all eyes search for his face in the boat as they approach the shore. He is not there!

And nor are six others. Of those who have gone, only the snivelling Pelgrom, for some unaccountable reason, is returning to them.

Pelsaert lands with as few words as those that greet him. The

Commandeur

simply parts the sea of people and makes straight for the tent so recently vacated by Jeronimus.

With the needs of justice now having been substantially served, it is time to focus fully on the other reason they have come here – to recover the Company’s goods. However, almost as if the evil of the men who have been hanged has now overflowed into the elements themselves, from the moment of their deaths a dramatic and relentless wind blows from the south, thwarting any attempts to send down the divers.

But this does not stop Pelsaert personally overseeing the retrieval of every possible bit of the VOC’s property in each and every corner of the islands, a man on a mission. With every little thing that makes its way back into the hold of the

Sardam

lightening his mental load, lessening the foreboding he feels about facing Governor-General Coen again, he becomes obsessed to the point of ludicrousness.

12 October 1629, Batavia’s Graveyard

When, at last, the howling southerly abates just a little, Pelsaert sends Skipper Jacob Jacobsz out in the yawl to recover a single cask of vinegar that was sighted by some of their intrepid fishermen on a nearby reef the day before.

The skipper, ever cheerful, promises to do just that and departs with four of his crew members and also Cornelis the Fat Trumpeter, who, having misplaced his trusty trumpet and consequently

feeling entirely useless, offers to help

. Pelsaert also takes advantage of the momentary respite in the weather to get the native divers to the wreck site to recommence operations.

There, they manage to bring to the surface 75 reals of loose change – a drop in the ocean compared with the tens of thousands of coins originally contained in the

Batavia

’s 12 money chests – and another cannon. The gasping divers, having held their breaths for as long as two minutes at a time, report that they are just on the point of attaching the ropes to the eleventh trapped money chest when

the wind suddenly picks up

, then

kicks

up even more.

Still Pelsaert won’t concede defeat for the day and thinks it might be possible to get that chest up once Jacobsz and his men return from their foray. Where are they, anyway? But, with their continuing absence, Pelsaert finally calls it a day. Due to the mounting seas, he and his divers beat a hasty retreat to the

Sardam

.

13 October 1629, Batavia’s Graveyard

Surprisingly, there is still no sign of the skipper and his men the following morning, though late that afternoon, just two hours before dusk, they see them on the distant horizon, beating their way back towards them against the prevailing sou’-wester!

There, do you see

?

Some do. Some don’t. Some claim to have had a clear vision of the yawl, its sails billowing; others say it was naught but a mirage – maybe even the phantom ghost of the

Batavia

herself searching for her earthly remains. What is clear is that, if it

was

them, they are now gone, for as the cursed wind picks up once more it is soon obvious that wherever they are there will be no return for them to the

Sardam

that evening. Pelsaert positively glowers in frustration.

20 October 1629, Batavia citadel

And now it is on again. On this morning, just as on two previous occasions, wave after wave of the Sultan of Mataram’s native soldiers charge forward with ‘

reckless determination

’, as the Dutch soldiers, armed Chinese merchants and Japanese samurai hold their ground, firing muskets and cannons into their very heart and never wavering.

The native soldiers, battered, beaten and bloodied, finally withdraw, leaving behind their many dead. Later that afternoon, the attackers have ceased their attack and entirely decamped. In the now deserted encampment, neatly laid out in rows, are the bodies of 800 freshly slaughtered Javanese soldiers and officers. As before,

the Sultan of Mataram has exacted a terrible price

on those who have failed to do what he commanded them to do.

24 October 1629, Batavia’s Graveyard

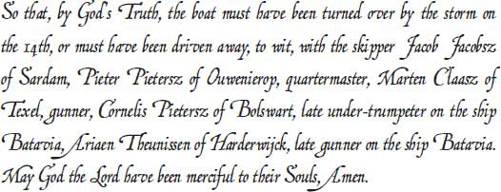

With the passage of 12 days and still no sign of the lost men, there is little hope left. Pelsaert is obliged to acknowledge in his journal the outcome of this search he has launched for a worthless, relatively insignificant cask of vinegar:

Click Here

Indeed.

While Pelsaert is saddened at the disappearance of Jacob Jacobsz, many of the Survivors and Defenders are devastated at the loss of Cornelis the Fat Trumpeter. Their favourite fat blowhard had survived a journey across the ocean, a shipwreck, the attack on Seals’ Island, the perilous journey to the High Islands and four attacks from the Mutineers . . . only to seemingly drown in the ridiculously unnecessary pursuit of a mere trifle.

Early November 1629, Batavia’s Graveyard

As poor weather prevails, all but Pelsaert start to weary of the salvage task, and the next opportunity to go after the eleventh remaining money chest comes on 5 November – alas, with the same result. After this latest failure, the divers have had enough. That is it.

They declare upon their manly truth

that no matter what they do, the money chest jammed under the cannon and anchor will likely remain there forever.

After pushing a few days more to collect a few more trifles, Pelsaert finally accepts the obvious and agrees. Waiting longer would only be to the detriment of their Lord Masters. It is time to pack up and prepare to go. God willing, wind and weather permitting, they will leave for Batavia as soon as possible – deviating only briefly from that course to

het Zuidland

to see if they can pick up any trace of the skipper and the four men missing with him.

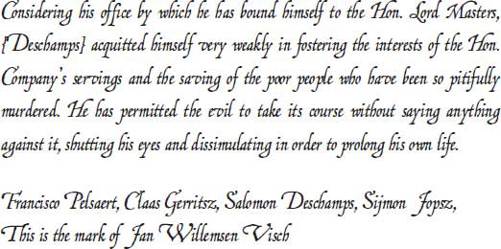

A few judicial loose ends have still to be tied up. Chief among these are the punishments to be meted out to the lesser Mutineers . . . such as Salomon Deschamps and Rogier Decker.

Notwithstanding the fact that Deschamps resumed his role as Pelsaert’s favourite functionary from the moment the

Commandeur

returned to the islands, his own guilt is deliberated on by a

raad

that includes the very man himself, and he faces

the further ignominy of having to record

in his very own hand the following:

Click Here

Of course, the worst he did was not only to throw in his lot with the Mutineers but also to strangle a child. Against that, as the child had already been poisoned by Jeronimus, there is no doubt that it would have died anyway, and all acts committed by Deschamps were forced upon him. So, take another note, please do, Salomon. ‘Using grace in place of rigour of justice, on the morrow, 13 November 1629, you and Rogier Decker are to be keel-hauled three times and after that be

flogged with 100 strokes

across the back and buttocks before the mast as an example to others.’