Batavia (59 page)

Authors: Peter Fitzsimons

The small trading post of Jacatra, which the Dutch renamed Batavia in the early part of the sixteenth century, has now become the teeming city of Jakarta. It had a population of 27,000 by 1673, 115,000 by 1700 and has 13,000,000 living in it today. These days, the chief barrier to journeying there is Jakarta customs, but for this little black duck that is barrier enough. (

Three hours

in the one queue! But don’t get me started.)

In the modern era, the Molucca Islands (Spice Islands) are no more than obscure specks on Indonesia’s eastern tip. When I enquired about visiting them in April 2010, the travel agent remarked she had never fielded such an enquiry in her 40-year career, and the answer eventually came back that, while I could get there by hitching a ride on a slow boat to China, it would be a minimum 17-day turnaround from Australia.

By the account of Giles Milton

in

Nathaniel’s Nutmeg

, the people who live there now have next to no idea how control of their islands was once so important that it could affect the destiny of nations.

As to the original settlement of Batavia, it survives, in part, right in the very heart of throbbing downtown Jakarta. What used to be its city hall, hall of justice and major warehouse are now respectively a museum, art gallery and maritime museum. The old citadel was the VOC headquarters for the whole of its operations in Asia, which included subsidiary VOC offices in Malacca, India, Bengal, Sri Lanka and Deshima (Nagasaki), until the Company was declared bankrupt at the end of the eighteenth century. The original building was torn down and replaced by a new one that was completed in 1850. In the late 1890s and early 1900s, it too was torn down, block by block, with each block thrown into the festering canal to fill it up. Still, with a good guide, a visitor to those parts can get a rough reckoning of where everything lay.

In the decades immediately after the wreck of the

Batavia

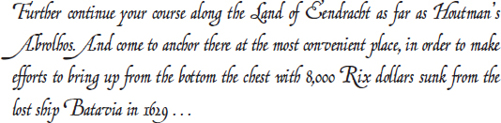

, the missing money chest was not forgotten. In 1644, one Dutch mariner, Abel Tasman, was given very specific instructions by the governor of the East Indies, Antonie van Diemen:

Click Here

A worthy goal, but the exhausted Tasman never got there, and in the end ignored those parts of his orders.

The decades passed, the centuries clicked over, and still the wreck of the

Batavia

lay beside the reef that she had struck, entirely undisturbed. The first small breakthrough in finding the wreck came in the late 1890s. At that time,

a Western Australian businessman by the name of Florance Broadhurst

had taken over one of his father’s ventures, mining some of the Abrolhos Islands for their guano deposits, and in the course of it had come across a number of old Dutch artefacts that, upon inquiry, he concluded must have come from the 1629 shipwreck of the

Batavia

.

A man of some wealth, on a subsequent trip to London he managed to secure an original copy of Jansz’s 1647

Ongeluckige Voyagie, Van’t Schip Batavia

, the book that first put the whole saga in the public domain. Upon Broadhurst’s return to Perth, he commissioned a Dutch-born Australian, Willem Siebenhaar – a chess-writer for

The Western Mail

– to do a translation, and on 24 December 1897 the translation first appeared in that paper. The English-language account was eagerly scoured for decades afterwards, providing many clues for subsequent researchers as to which specific islands the whole ordeal had taken place on and where the wreck might be found.

Leading the charge was Henrietta Drake-Brockman

, the amateur historian and well-born Perth journalist with the

Western Mail

– daughter of Western Australia’s first female doctor – who first heard the story when she was 12 years old, from her friend, the daughter of Florance Broadhurst, and became smitten with it.

As an adult, Drake-Brockman began following leads, writing to authorities in the Dutch Republic to get more information and talking to those she could find who were familiar with the islands off Australia’s west coast in the rough latitudes described, and she drew her conclusions on a map. Now, the most obvious place to start looking for the wreck was the ‘Pelsaert Group’, the southernmost of the three groups of islands that make up the Houtman Abrolhos island chain, which includes locations such as Wreck Point and Batavia Road. These names were bestowed back in the 1840s by the British survey ship HMS

Beagle

– which had previously risen to fame by carrying a young British botanist by the name of Charles Darwin to Australian climes – after her officers discovered ancient ship wreckage there and assumed it must be the remains of the

Batavia

.

The more Drake-Brockman looked into it, though, the more she became convinced the wreck would be found in the Wallabi Group, some 30 miles to the north, where there were indeed a couple of islands that had some native wallabies on them, and one of those islands had water. She began to search, even as she continued to write about it.

When her fictional account of what had happened,

The Wicked and the Fair

, was published in 1957, followed by her non-fiction account (borne from original research) in 1963, it heightened interest further, most particularly among the Western Australian locals. And yet there was still no breakthrough, not that Drake-Brockman let up for a minute. A young friend of her family’s was the rising journalist at the

Daily News

, Hugh Edwards, a keen diver in his spare time, whose favourite book as a youngster was

Treasure Island

.

‘You

must

find the

Batavia

for me,’ she would say whenever they met, peering through the cigarette smoke she had just blown in his general direction, before tapping her long cigarette holder on the ashtray. A formidable woman was Henrietta Drake-Brockman. Hugh, too, was very interested, but he was flat out working as a journalist, raising his young family and diving on other wrecks.

Nevertheless, the clues were building. In 1960, an old man known as ‘Pop’ Marten was on the island in the Wallabi Group called Beacon Island, when he decided to dig a hole to put a clothes line in. As soon as this father of a local cray fisherman pressed his shovel beneath the surface, it hit something solid, whereas the surrounding soil was soft.

He got down on his hands and knees

to investigate and discovered . . . a human skull.

Well, what was a man to do? Of course, he covered it up again and decided to do nothing.

They didn’t like visitors in these parts

, and calling the police and enduring all the attendant carry-on, perhaps of filling out forms and making statements, giving testimony at the Coroner’s Court and all the rest, was just more trouble than it was worth. Still, it was a cracker of a story to tell the few visitors they did have, and it wasn’t long before the police got wind of it anyway.

Two policemen from the nearest mainland town

of Geraldton duly arrived and investigated, without coming to any solid conclusion other than that the bones were likely very old indeed.

The find did, however, generate a small item in the Perth

Daily News

, where it was quickly spotted by Hugh Edwards. He knew it on the instant: the body had to have come from the shipwreck of the

Batavia

!

Edwards was soon able to convince his editor at the

Western Mail

that it was worth mounting an expedition to Beacon Island – not that any of that excited Henrietta Drake-Brockman.

‘It’s the wrong island, you silly boy. Goss Island is where you should be looking!’ she said, many times, naming an island about two miles from Beacon Island, where she was convinced the whole thing had occurred.

As to the wreck itself

, she was certain that would be found on nearby Noon Reef.

Hugh headed off with his newspaper-photographer colleague Maurie Hammond with Henrietta Drake-Brockman’s exhortations ringing in his ears. Alas, with just two of them on this expedition they weren’t able to find anything of significance, though they were at least able to convince themselves, after some exploration, that Goss Island was not the right one. Some quick digging around Beacon Island, near where Pop had found the skeleton, revealed nothing but a bone that proved upon examination to have come from the wing of a large seabird. They briefly dived out on nearby Morning Reef but found nothing and, with time running short on their ill-equipped expedition, returned to Perth with little to show for their trouble, bar a few ‘colour’ articles that Hugh was able to write for his paper.

Not long afterwards, though, Pop was digging again, burying some rubbish, when his shovel connected with something metallic.

It proved to be brass

, looked a lot like the base of a lamp and had some writing on it, spelling out the year in Roman Numerals, MDCXXVIII, with the name CONR AT DROSCHE. It was some years before it was realised that this last was the name of a noted German trumpet maker . . .

(Me? I would love to think it was the very trumpet once blown by my favourite: Cornelis the Fat Trumpeter!)

For the moment, though, all the finding of the ‘lamp base’ did was heighten talk among the cray fishermen that there was something strange about these islands.

Enter Geraldton builder and diving enthusiast Max Cramer, a man of equal parts capacity and enthusiasm for any interesting ventures – most particularly if they involved going underwater in search of shells, then his great passion. In early 1963, Hugh Edwards invited Cramer to join him on a highly successful expedition to find and dive on the 1727 wreck of the

Zeewyk

in the southern Abrolhos, where

Cramer proved to be a good diver

, team member and man.

So, when Max suggested that Hugh hand to him all the information he had on the likely whereabouts of the

Batavia

, Hugh decided to trust him. He handed over a folder of cuttings and documents on the shipwreck, got out his Admiralty map and pointed to the most likely place where he thought the wreck would be found, saying he should particularly concentrate on Morning Reef, which, on his own recce two years earlier, he had only been able to search for a short time. It was just a mile or so from Beacon Island, which Hugh still felt was the site for the whole seventeenth-century drama.

A short time later, Cramer was on Beacon Island with his brother Graham and friend Greg Allen, getting ready to dive on the morrow, when a cray fisherman by the name of Dave Johnson, who lived there, asked them what they were up to. Max told him they were going out to Morning Reef to look for a wreck he thought was there.

Dave looked at Max. Paused. Max looked back. ‘I know where it is,’ Dave said slowly. For years, he had noticed what looked to be blocks of stone and some cannons on the seabed at a particular spot on Morning Reef where he sometimes set his pots, and, if these fellows were looking for it, well, that was where it was. Like Pop,

he was not crazy about visitors

, but if they were going to discover it anyway, he might as well tell them.

The following day, Dave took them out to the approximate spot. Max put on his face mask and was the first to dive below. As he records in his book

Treasures, Tragedies and Triumphs of the Batavia Coast

, this is what awaited him:

My first thought was that a bomb had gone off

. There was nothing of the wonderful ship left to see. Six bronze cannons sat four metres up on both sides of the six-metre depression which was partially filled with sand. There were also mysterious objects covered in seaweed which soon materialized into old anchors and iron cannons scattered towards the reef . . .

Eureka!

It was early June 1963.

Hugh Edwards was at home having dinner when he heard the news over the ABC Radio. A reporter from the Geraldton bureau of the ABC was intoning in those classically emotionless tones of the broadcaster born, ‘

Max Cramer and a group of Geraldton divers

have located a shipwreck in the Abrolhos Islands, believed to be the 1629 Dutch East Indiaman

Batavia

.’

In response, Hugh had just one thing to say: ‘TAXI!’

Or near as dammit. (‘Bloody Max!’ might have also figured.) By dawn the following morning, Hugh was at the airport and then on his way to Geraldton to meet up with Max and cover the story for his newspaper before returning to Perth and beginning to organise a major diving expedition on the wreck himself.

On the sparkling morning of 29 July 1963 – Hugh’s 30th birthday, by the by – he was able to dive on the reef himself and see the vision splendid before him, just as Max Cramer, who was with him on this expedition, had described it.

Cannons, coins, artefacts, anchors

, navigation instruments, all there, even more impossibly beautiful and achingly evocative than he had long dreamed.