Ashes of Fiery Weather

Read Ashes of Fiery Weather Online

Authors: Kathleen Donohoe

Copyright © 2016 by Kathleen Donohoe

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to

[email protected]

or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Donohoe, Kathleen, author.

Titles: Ashes of fiery weather / Kathleen Donohoe.

Description: Boston : Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, [2016]

Identifiers:

LCCN

2015037241 |

ISBN

9780544464056 (hardback) |

ISBN

9780544526693 (ebook)

Subjects:

LCSH:

WomenâFiction. | Fire fightersâFiction. | Irish American familiesâFiction. |

BISAC: FICTION

/ General. |

FICTION

/ Literary.

Classification:

LCC PS

3604.o5646

A

89 2016 |

DDC

813/.6âdc23

LC record available at

http://lccn.loc.gov/2015037241

“Our Stars Come from Ireland” from

The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens

by Wallace Stevens, copyright © 1954 by Wallace Stevens and copyright renewed 1982 by Holly Stevens. Used by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

All rights reserved.

Cover design by Brian Moore

Cover photographs © Ivan Vega / Getty Images (window); © Justin Beck (NYC skyline)

v1.0816

To Travis and Liam,

the two I cannot do without

These are the ashes of fiery weather,

Of nights full of the green stars from Ireland,

Wet out of the sea, and luminously wet,

Like beautiful and abandoned refugees.

âWallace Stevens, “Our Stars Come from Ireland”

CHAPTER ONE

April 1983

THE BAGPIPES TOOK UP

“Going Home” as the firemen bore the coffin out of the church.

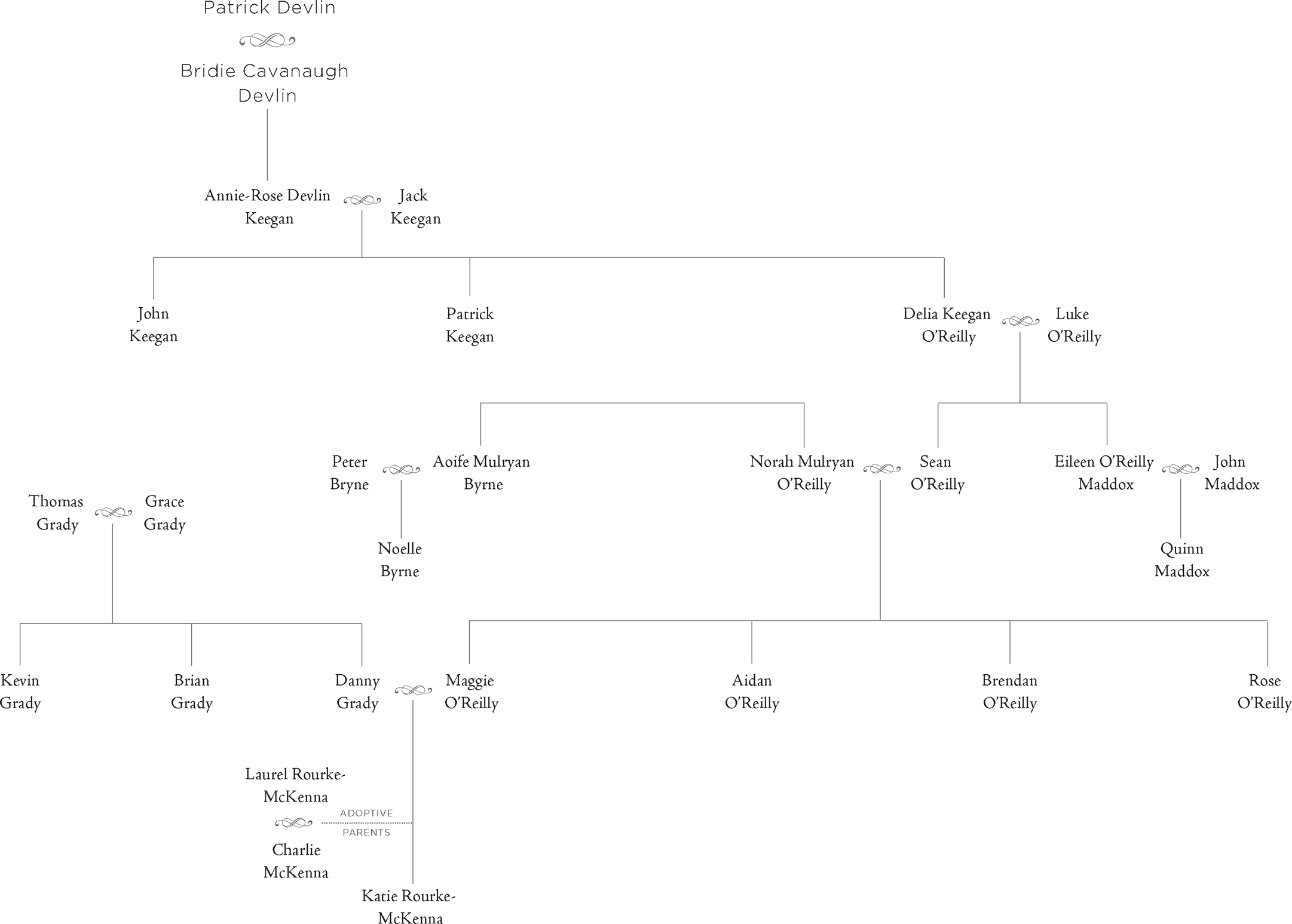

Norah O'Reilly paused on the threshold of the heavy double doors, thrown open as they'd been on her wedding day, a gray November morning, altogether better suited to the end of the story than this soft April afternoon. A warm spring rain had begun to fall during the Mass.

Norah scanned the faces of the assembled firemen, three deep from the curb to the street, skipping the mustached, the older guys, the not-tall, the dark-haired, the obviously non-Irish, the ones in white caps, who were the officers. She didn't see Sean. She saw Sean a hundred times.

Cameras flashed as she stepped fully outside. For ten years, she'd been an understudy in this play, but she'd never once rehearsed. She didn't know her lines, forgetting the names of longtime friends, missing cues, blinking stupidly at outstretched hands and stepping into hugs moments too late. Wherever she went, she left whispers in her wake.

Poor Norah.

This morning, while savagely biting the tags off her new black dress, she'd resolved not to cry in public. She would be brave. Not like a fireman, but like a Kennedy. The Kennedys were always burying each other. They knew how it was done.

In the crowd, Norah spotted Amred Lehane with his hand over his heart. He knew, of course, that civilians were not supposed to salute. Amred, the buff. She recalled Sean explaining that to her. A buff was a fire department fanatic. They often knew more about the history of the department than the guys themselves. Some buffs were attached to particular companies, like Amred, who belonged to the Glory Devlins and whose insistence on calling them by the company nickname instead of the number was so strong that the men had caught the habit.

The firemen who had not come into the church for Mass, the ones who hadn't known Sean personally, and those from other cities surely spent the service having a breakfast beer across the street in Lehane's, the bar Amred and his sister owned. Amred would have told them how Sean used to bartend there, that he and his Irish wife had met there.

Poor Norah.

She supposed that was her name now.

The men eased the coffin down the steep steps of Holy Rosary. Norah knew that they would not let go of Sean, but rather than watch, she lifted her face to the sky.

Happy is the soul rain falls on.

An Irish proverb. Rain on the day of a funeral was good luck.

She sensed her brother's eyes on her. All three of her brothers had traded Galway for England. Two had called to tell her how they'd liked Sean the time they met him. Only Cathal got on a plane.

Norah told their parents not to come. Her relieved mother promised to have a Mass said for Sean in their own church. Her sister, though. On the phone, Aoife made no mention of emergency passports and plane tickets. She only cried and said she'd have Noelle make a sympathy card for her cousins. Aoife's daughter was ten, a year older than Maggie.

Norah started, then looked for the children. There were three, yet in four days they seemed to have multiplied, surrounding her with their confused blue eyes and moving mouths. Four-year-old Brendan was clinging to the skirt of her dress. Surely she'd had hold of him most of the way down the aisle. When had she let go?

She pried the fabric out of Brendan's fist and grasped his hand so hard he looked up at her in surprise. His hand was mucked with chocolate licorice, which she'd trusted would keep him occupied during Mass, even though the smell made her sick. Her dress, long-sleeved and too warm for the day, was tight over her breasts, which were already fuller. Nobody knew.

Aidan stood beside Brendan, wearing the suit and tie he'd worn this past Sunday, for Easter. Aidan would turn nine two days before Maggie turned ten. Irish twins. Norah located Maggie slightly behind her and reached back with her free hand, but Maggie shied away and then stared back at Norah, daring her to beckon again. Maggie, as the only girl, believed she was Sean's favorite, but it was Aidan who was his heart.

Maggie and the boys had Sean's eyes, a striking blue a shade darker than her own. Maggie glanced at her grandmother, wanting to be her ally instead of Norah's, but Delia, her gaze fixed firmly ahead, didn't seem to notice.

Suit yourself, Norah thought and turned around.

Sean's eyes were his mother's eyes. Delia O'Reilly, beautiful still at sixty-five. She'd been an elementary school principal, formerly a teacher, and there was something in her bearing that suggested it, Norah thought. She expected to be listened to. Sean had often called his mother brave. Back in the 1950s, not many people got divorced. Sure as hell nobody Catholic, he'd say. Many of her students had come to the wake, clearly self-conscious in their dress-up clothes, passing right by Norah. The boys kept their hands in their pockets as they mumbled that they were sorry. The girls had more poise, but it was easy to tell the ones who'd never been to a wake before by the way their wide eyes couldn't leave the open casket. Former students had come as well, college-aged if not in college, and they shook Norah's hand and told her they remembered Sean coming to their classroom in his uniform, and they remembered visits to the firehouse.

Norah, too, remembered Sean saying these kids pulling the fire alarm boxes accounted for probably half their runs. Delia would say that's why it was important that he talk to them. He would shake his head, but he never said no to her.

The coffin arrived at the bottom of the steps and Norah started down, going slowly, for Brendan. She sensed her brother tense. Cathal was ready to grab her arm if she stumbled. The cameras clicked in chorus. Aidan pressed Sean's helmet against his stomach. She made a mental note to be sure to let Brendan get a chance with the helmet. She would make Aidan give it to him as they were leaving the cemetery, when the pipers began “Amazing Grace.”

A few members of the FDNY's pipe and drum band had played at their wedding too, though Sean hadn't been a fireman yet.

He'd been waiting to get on the job, increasingly worried that the city's money troubles would keep it from hiring more firemen, needed as they were. When he did get called, only a few months after the wedding, Norah had been too relieved to fret about his safety. A better paycheck and a steady one, she'd thought, as though he'd been hired to sell insurance. They could move out of his mother's house and into an apartment before the baby came.

Cross Hill Cemetery had been closed to new burials for a decade at least. But an exception was being made so Sean could be

laid to rest,

as the priest put it, near his grandfather and great-grandfather, firefighters both. The newspapers were making much of it. “Legacy of Bravery,” said one headline.

And, of course, Eileen was in the papers too. The articles about Sean all mentioned that his sister had joined the class-action lawsuit against the FDNY and that she'd graduated from the academy last year, in the very first class to include women.

The procession halted. Three times, Monsignor Halloran blessed the casket with holy water, his spotty hand quaking. He'd baptized Sean too.

The firemen lock-stepped a turn and hoisted the coffin onto the pumper. The honor guard took up their places, four on either side of the pumper and two standing on the back. Firefighter Eileen O'Reilly was one of the four.

Her red hair was pulled back in a tight bun at the nape of her neck. When she got on the job, she'd cut it so it was above her shoulders, but she refused to have it short-short. She was already being called a dyke, she told Norah with a crooked smile. Couldn't give them more ammo. Norah laughed and felt she was betraying Sean, who'd found nothing funny at all about his sister's new career.

The pipers started “Garryowen.”

Eileen's back was straight, her face impassive. Eileen looked like she was playing dress-up, as though she'd stolen Sean's Class-A uniform for the occasion.

Joe Paladino was escorting Delia. Sean, apparently, had left instructions with this request. But it was Nathaniel who should have been beside her, and Sean should have realized this. Nathaniel Kwiatkowski, whose gentle voice was accented with both Poland and Brooklyn, had known Sean his whole life. That should have trumped the goddamn holy fire department. Nathaniel was there, of course, not far behind Delia, but like an ordinary mourner.

Indeed, Joe startled Norah in all ways when, straining for composure, he explained Sean's wishes to her.

Sean never told her any details about his funeral. Firemen loved to say you never know when you get on the truck what you'll find when you get there, but Norah had spent her marriage convinced that none of them believed they might die on the job. That it was possible, that they very well might be, she'd thought a secret kept by the wives.

But choosing Joe to escort his mother at his line-of-duty funeral meant that Sean understood. And if Sean had, then all the guys from Sean's firehouseâthe funny ones and the shy ones and the ones who bullied the probies worse than if the firehouse was a frat house, the swaggerers, the ones so kind they were like Irish priests in old moviesâthen all of them knew that they might, one day, go to work and get killed.

At the bottom of the steps, the fire commissioner shook Norah's hand and then Delia's. Then Mayor Koch did the same.