As Easy as Falling Off the Face of the Earth (10 page)

Read As Easy as Falling Off the Face of the Earth Online

Authors: Lynne Rae Perkins

L

ater, when Del was putting the generator back into the Willys, Ry said, “So, how come twisting the wires together would be shoddy, but hooking up a muffler with a coat hanger isn’t?”

“It is,” said Del. “But that was an emergency. It was a desperate measure.”

“Isn’t it an emergency when your car dies in the middle of nowhere?” asked Ry.

“It could be,” said Del. “If your life was in danger. Otherwise, it’s just an interesting situation. You could even think of it as fun.”

He had soldered the broken wire together over a small fire they built. Ry had helped lay the fire and he held things in place while Del soldered, but he had the feeling that Del would have managed just fine by himself.

The plan had been to walk to a town, find a mechanic to solder the wire, maybe get a ride back. But while they were at Cecile’s, Del found this dinky little soldering tool in a jewelry-making kit. The kit was in the crafts section, a dusty pile of battered boxes. Del happened on it by luck, while Ry searched for food they could call breakfast.

It turned out to be a parallel-universe breakfast. A long shelf-life version; you didn’t want to know how old any of it was. Just be like an astronaut and choke it down. He picked jerky, pickled eggs, potato chips, and orange soda. Corresponding to bacon, scrambled or fried, home fries, and juice.

It was not only the food that was of indeterminate age at Cecile’s. Without even exploring very far, Ry found small American flags with the wrong number of stars, yellowing comic books with heroes he had never heard of, and music on cassette tapes. The cars in the postcards all looked like—well, Carl’s or Del’s, so he couldn’t really draw any conclusions there. But the little girls and women were wearing dresses, an old-fashioned kind with big full skirts. Maybe it was more of an antique shop. He brushed past a spinning rack of brochures that illustrated a variety of ways of going to

HELL

in hand-drawn wavy letters, and found himself in a small section

of actual groceries. Maybe this was a better idea. He picked up a box of Cheerios. The sell-by date stamped on the top was two years past. The contest deadline on the back of the box, likewise. Antique cereal. It might still be okay. According to legend, Twinkies lasted for seventeen years. Maybe Cheerios did, too.

He decided to go with the stuff up front. It was probably the faster-moving stuff. Relatively. He went back up to the counter. Del was already there, taking money from his wallet to pay for the food and—a jewelry kit?

“You don’t by any chance have a cup of coffee you could spare?” he asked Cecile. Who was herself ageless, in a way. And preserved.

Her smile was lively.

“You bet,” she said. She disappeared through a curtained doorway and returned with a Styrofoam cup of steaming brown toxins.

“Don’t worry about it,” she said when Del asked her how much.

“Do you need a lift?” she asked. “I can call someone.”

Del said no thanks, and as they started their hike back toward the car, juggling the generator, the jewelry kit, “breakfast,” and Del’s coffee, Ry asked him why.

“No sense making someone go out of their way,” said

Del. “We can probably get a ride with someone who’s already going where we need to go.”

And even as he spoke, he turned and raised his thumb, along with his coffee cup, at a passing tractor trailer. The trucker tootled at them and eased his rig to a halt a few dozen yards ahead.

“Don’t worry,” said Del as they trotted toward it. “Most people are nice.”

“I’m not worried about ‘nice,’” said Ry. “Carl was ‘nice.’”

Del smiled his almost-smile.

“And most people are better drivers than Carl,” he said.

Ry was worried, a little, about “nice.” Maybe more than a little. Like five-eighths. But he didn’t say so.

His inner voice issued warnings. He climbed up into the cab anyway. Why did he? Because sometimes it’s hard to tell if your inner voice is wise, or if it’s made out of your fears and your mother’s fears and too many psycho-killer movies all balled up and clamoring. So he went along with the crowd outside of himself—Del and the sunny day and the shiny truck. It could have gone wrong, it could have been bad, but it turned out okay. The guy was just a guy. He knew how to drive. Before

long they said, “Thanks” and climbed back down.

The Willys looked like home, though.

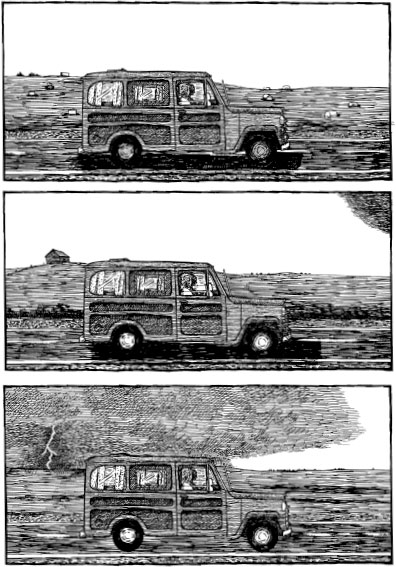

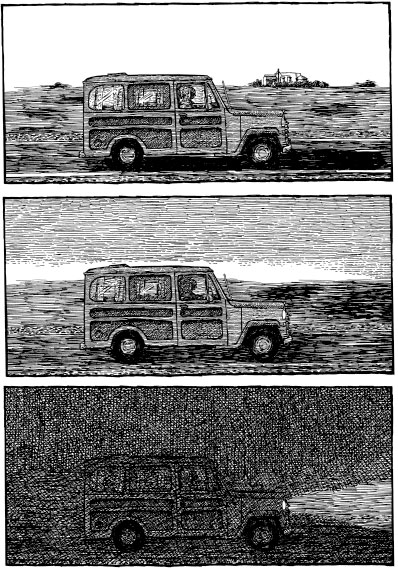

When they got there, they made the fire. Del soldered the wire and put the generator back into its place. They climbed in, the Willys started up, and off they went.

They had not been traveling long when, in the distance, a dot appeared. A dot with its headlights on, wavering from side to side, growing larger. Coming at them in their lane, skipping back over to the other. Boxy now, and whitish, way bigger than a bread box. A head, silvery, hanging out the window; a hand, too, reaching to adjust the outside mirror. Maybe for a better look at the other dot growing into a box behind it. That one had a flashing red light on top. It was catching up.

As soon as they knew the first car was Carl, Del eased off the road out into the dirt where it was safe. No sooner done than Carl whizzed by, close enough that they could see his eyes, and the delight and terror in them. He saw them, too, and maybe it was trying to recall who they were that made him lose what grasp he had of what he was doing. The big old car went zigzagging; it tipped up onto two tires, the two on the right. For a long half second, it could have come back down on four or tipped right over, either one. It went over. And over again. And lifted

slightly once more, but fell back down with a whomp.

Light wisps of smoke rose from the folded hood as the cop car pulled off, a distance behind. Wisps thickened to plumes as the cop doors flew open. Del had backed up, turning, as if to head down there, too. But the cops jumped from their car and ran, and it was plain that they were the ones in a position to do anything.

The plumes of smoke inflated to clouds as the policemen tried to open the door but couldn’t. One of them reached inside, lifted Carl from under his armpits, hauled him mightily through the open window. Carl’s arms wrapped around the cop’s shoulders in an embrace, like a child with his mother. The cop set him down on the ground, but when his legs crumpled and he started to sink so rapidly, both men were there, lifting him back up. Hurrying him away, they looked back over their shoulders. The thick smoke grew thicker and blacker; a dark geyser poured up into the clear air.

And then, like the striking of a match, there was flame that exploded into fire. The car was a torch. It was impossible to look away from a fire like that. Del and Ry and Carl and the policemen all watched it, transfixed.

When the flames gave way to smoke again and another flashing light–topped vehicle could be seen, the

two burly cops led subdued, small Carl to their car. Del pulled quietly back on to the road. There was nothing he could tell the police that they wouldn’t see for themselves immediately. The Willys headed east. They moved on. Everyone moved on, to whatever happened next.

Everyone thought about the fire, though, about what had happened and what could have happened. Del and Ry didn’t say much for a while. Ry thought about Carl, all small and round and frightened. He thought about how he himself had been in that car, with Carl driving.

But there was a limit to how long he could think about all that. It got too deep. He had to rise to the surface.

“So,” he said to Del brightly, “are you from around here, or are you just passing through?”

T

hey stopped in a town in North Dakota for lunch and to get gas. It was late for lunch. The place was almost empty.

Ry was going to have a burger, but then he thought he should eat some vegetables, so he ordered a BLT. And a milkshake.

“At least he didn’t get killed,” he said. Meaning Carl, and Del got that. He had been thinking of Carl, too. And something else.

“How old is your grandfather?” he asked.

“I don’t know,” said Ry. “Seventy, something like that.”

“Is he pretty healthy?” asked Del.

“He plays tennis,” said Ry. “He skis. And water-skis.”

“How about mentally?” asked Del. “Do you think he would ever wander off? Is he like Carl?”

“No,” said Ry. “He’s not like that. He’s still all there. He’s probably the smartest person in our family.”

So, if he wasn’t answering the phone, or returning Ry’s calls, why wasn’t he? It had to be something just weird and simple. As weird and as simple as how just saying the words “our family” made Ry wonder if he still had one. Where was everyone?

He was glad there was Del. Otherwise, he might be living under that bridge in New Pêche. In a cardboard box.

“You can imagine fifty million things,” said Del, as if he had heard Ry’s thoughts. “But only one thing happened. And most of the time, it’s just a mix-up, not something bad. So you might as well not worry. Just go find out.”

“I don’t think I can help wondering,” said Ry.

“That’s why we’re going there,” said Del.

The waitress arrived with their food. It looked great. Like food for the gods.

“I didn’t order a pickle,” Del said to the waitress.

“Oh, we always put a pickle on,” she said pleasantly.

“I don’t like pickles,” said Del. “I really don’t even want it on the same plate as my food.”

“Jeez,” said Ry. “It’s just a pickle. Here, I’ll take it.”

The waitress lifted her eyebrows and moved on.

“I can still smell it,” said Del. “I really dislike the smell of vinegar.” He said “vinegar” the same way he had said “shoddy.” The same way you might say “cannibal.” Ry thought he was overreacting a little.

Still, there was a stack of clean plates on a counter nearby, so he went and got one and brought it back. He transferred Del’s sandwich and fries to the clean plate, saying, “My hands are clean. I just washed them.” He set the used plate on the counter. Sitting back down, he said, “What about my pickle? Will it ruin your lunch if I have a pickle?”

“I don’t know why you would want to,” Del said. “But it’s your life.”

Ry ate both pickle spears. They were tart and crisp and succulent. The soft white bread was homemade. The bacon melted and crunched in his mouth. The tomato was ripe and tasty. The lettuce was just lettuce, but it did what it was supposed to do; it was green. The milkshake, chocolate, was cold and thick, yet not completely impossible to suck up through the straw. And there were fries. Fresh, warm, tender-crisp, and salty.

Ry was suffused with a sense of well-being.

Del said, “Let’s just drive straight through.”

“What?” said Ry. Because he had been immersed in

eating. By the time he finished saying it, he knew what Del had said; it had registered. Del opened the road atlas he had brought in with him. He flipped back and forth between pages marked with forefingers and thumbs. He had pulled out reading glasses, and they slipped down his beakish nose, making him appear older. Almost old. Or maybe that was because his cap was off, and with his head tilted down his scalp shone from beneath thinning hair.

“Might as well,” he said. “See how far we can get, anyway. I think we can make it by morning. Then you can yell at your grandfather for not answering the phone.”

He looked up at Ry. His grin was impish. Now he seemed younger again.

“Wasn’t there stuff you wanted to do on the way?” asked Ry. “Errands?”

“Nothing that can’t wait,” said Del. “I can do it on my way back. Let’s just go.”

So they headed out across the rest of North Dakota. There was a lot of that left.

Not to mention all that Minnesota.

Not to mention all that Wisconsin.