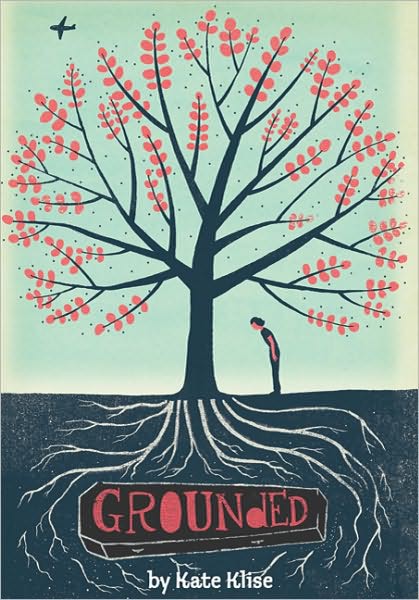

Grounded

Authors: Kate Klise

Give sorrow words; the grief that does not speak

Whispers the o’er-fraught heart and bids it break.

—William Shakespeare,

Macbeth

Grounded in Digginsville

I’m alive today because I was grounded. Maybe that sounds odd to you, but it’s true.

I was grounded by Mother for going fishing at Doc Lake without her permission. That’s the only reason I wasn’t in Daddy’s plane when it crashed and killed him, my brother, and my little sister.

I was home sulking on the front porch, mad that I couldn’t go flying with the others. Mother was inside, ironing in the kitchen and listening to “Swap Line.” That was the name of a radio program. For five minutes every hour on the hour, folks would call in to the radio station and try to swap something they had for something somebody else had.

My mother loved “Swap Line.” Nothing entertained her more than hearing people describe the junk they had in their basements and attics. For a woman who kept her house neat as a pin, listening to “Swap Line” was like listening to people confess their sins. Mother kept the kitchen radio turned on all day long so she wouldn’t miss it.

Even from the front porch, I could hear her through the screen door, talking to the radio while she ironed.

“Bud Mosley, you’ve been trying to swap that cracked aquarium for three

weeks

,” Mother said, howling with delight.

My mother knew everyone who called in to “Swap Line.” She even knew their junk. In bigger cities, folks had news to listen to every hour. We had “Swap Line.”

“Daralynn!” she called to me from the kitchen. “Come and listen to ‘Swap Line.’ It’s a good one.”

“I don’t want to listen!” I hollered from the porch.

Truth was, I

did

want to listen. I was as hooked on “Swap Line” as anyone. But I suppose on that Sunday afternoon in late October I wanted to pout more.

I was kicking leaves in the yard when the state trooper’s car pulled up in front of our house. It was

Jimmy Chuck Walters. He’s the one who told us about the engine failing on Daddy’s plane.

He told us in the kitchen. When he finished, Mother didn’t cry. She just closed the front door, turned off the iron, and called Mamaw, my grandmother, who lived next door.

Right away, they started planning the funeral:

One service or three? Granite gravestone or marble? A reception at church or at the house?

I wasn’t much help in making the funeral arrangements. My brain couldn’t take in all the information. It was like an old tree you can’t fully see by just standing in front of it. You have to step around it slowly to understand how big it really is.

The world had changed. That much I knew.

But I confess the first thing I thought after I heard about the crash was:

I’d swap Bud Mosley a cracked aquarium for this.

My second thought was:

If I’m the only kid left in my family, I bet Mother won’t ground me as much anymore. I bet I won’t get grounded again for the rest of my life.

Hello, Dolly

You wouldn’t believe all the dolls I got after that.

For days, people drove up our driveway. Usually they’d leave their cars running while they knocked on the front door.

“I’m so sorry, honey.” That’s what most folks said when I opened the door. Then they’d hand me a doll.

Others whispered: “We’re praying for you.” And then they’d hand me a doll.

Cloth dolls. Plastic dolls. Creepy baby dolls with giant pink faces. Curvaceous Barbies. Barbie knock-offs. Beautiful Crissy dolls with glossy red hair just asking to be pulled.

I was buried alive in dolls.

And unlike the crockpots filled with ham and beans that arrived with the owners’ names written on masking tape, the dolls weren’t meant to be returned. They were for me. To keep.

One day Miss Avis Brown from

The Digginsville Daily Quill

came to the house. She wrote a story about me and all the dang dolls I was getting. It ran on the front page under the headline:

Hello, Dolly!

12-Year-Old Girl Receives 237 Dolls

After Family Tragedy

That’s when a lot of people in town started calling me Dolly instead of my real name, which is Daralynn Oakland.

What everyone forgot was that

I

wasn’t the one who

liked

dolls. That was my little sister, Lilac Rose. She was Mother’s favorite.

Lilac Rose was named after the flowers Daddy gave Mother on their first date. Just like her name, Lilac Rose was pretty and prickly, especially when Mother brushed her hair.

Even at the funeral home, Mother spent hours bossing Lilac Rose’s golden hair into perfect banana curls as she lay stretched out in her casket.

Nearly every bone in Lilac Rose’s body was broken, but she sure looked pretty. That was important to Mother.

Lilac Rose was nine years old when she died.

Wayne Junior was sixteen. He was Daddy’s favorite. My brother wanted to be a pilot for Ozark Air Lines, just like Daddy. He probably could’ve done it, too. Wayne Junior was smart and good at math. But he wasn’t as handsome as Daddy.

My daddy was the most handsome man in Digginsville. Every lady in town admired his blue eyes and sandy-blond hair. Even the girls in my class used to say he was more handsome than Paul Newman and Robert Redford combined, which filled me with pride and embarrassment, combined.

I didn’t inherit good looks from my parents. With my brown ponytail and hazel eyes, I looked more like Daddy’s sister, Aunt Josie, only without her makeup and dyed red hair.

It was a rare occasion to see Aunt Josie without her Passion Red lipstick and drawn-on eyebrows. In fact, the first time I ever saw Aunt Josie without her makeup was the day of the crash. She burst through our front door without even knocking.

“I just heard the news from Jimmy Chuck Walters!” Aunt Josie wailed. “It can’t be true! Oh, Hattie, is it true?”

“It’s true, all right,” Mother said stonily.

That made Aunt Josie cry harder. “Those beautiful children,” she moaned, collapsing in our front hallway. “Lilac Rose. Wayne Junior. And my sweet baby brother!”

Mother just stood there with her hands on her bony hips, staring straight ahead.

“How can it

be

?” Aunt Josie continued. “Oh my God in heaven above!”

Mother snapped. “Don’t make a show of it, Josie,” she directed. And then she walked upstairs and started picking out clothes for Lilac Rose, Wayne Junior, and Daddy to wear in their caskets.

I might not have been Mother’s favorite, but I wasn’t in last place. That distinction was held by Aunt Josie, who’d been at the bottom of Mother’s list for as long as I could remember.

Aunt Josie’s crying that day of the crash—the messiness of it all, the display of uncontrolled emotions, the fact that Aunt Josie wasn’t even wearing lipstick—was contrary to everything my mother

stood for. All she could do was wait for Aunt Josie to be on her way.

Looking back, I know Mother felt sad. I’m sure of it. But it’s almost like she didn’t know how to

do

sad. Not like Aunt Josie did, anyway. Crying wasn’t Mother’s style, just like wearing slacks wasn’t her style.

So instead of getting sad, Mother got mad. A week after the crash, she paid Marvin Kinser from the hardware store thirty dollars to put a lock on her bedroom door. For almost nine months after the crash, I could hear Mother in her room, pacing the hardwood floor and slamming things down hard on her marble-top dresser. That’s how mad she was.

At first, I hollered up to her whenever I heard “Swap Line” come on the kitchen radio. I knew she couldn’t hear it upstairs. Mother didn’t believe in keeping a radio or television in the bedroom. So I’d yell up the stairs: “Swaaaaaap Liiiiiiiine’s on! You’re gonna miss ‘Swap Line.’”

Before the crash, Mother always wanted to know when it was on. That’s why I kept hollering up to her. Sometimes I added, “It’s a good one!” even though I couldn’t hear what was being swapped.

I did that for weeks. I thought listening to her

favorite radio show might cheer her up a little. But she never answered back. Somehow or other Mother had lost interest in hearing about the junk in other people’s lives. Maybe because for once we had a fine mess of our own—and not a soul to swap it with.

A Job to Die For

What you remember from funerals are the little things. The tiny details.

The deep scratch in the front-row pew you never noticed because you never sat that far up before.

The geometric patterns that church lights throw on glossy caskets.

The fact that caskets come in different sizes and colors. (Lilac Rose’s was pearl white. Wayne Junior’s was midnight blue. Daddy’s was gray.)

The fact that caskets have handles for carrying.

The way the smell of flowers can make a person sick. Mother told me later that if she smelled one more bouquet of roses, she’d surely vomit.

The embarrassment of having 300 people,

including every teacher in town, looking at your backside. The even worse embarrassment of being seen wearing a calico dress and white gloves. Mother insisted on the gloves because my fingernails were still grimy from replacing my bike chain the week before.

Lilac Rose loved to wear gloves. She liked pretty things. I told Mother she ought to put my sister in her dance recital costume with all the sequins and spangles. That was Lilac Rose’s favorite dress. But Mother ignored me and dressed my sister in her white Easter dress and gloves.

She dressed Wayne Junior in his brown corduroy suit. I stared at him all during the funeral, just waiting for him to pop up like a jack-in-the-box and say it was all a joke, like he’d said after her gave me that trick pepper gum that was supposedly cinnamon. But he didn’t move.

Neither did Daddy. He was stretched out in his casket wearing a starched Ozark Air Lines uniform. Mother even propped his pilot cap on his head. It was a darn shame his eyes were closed because Daddy had eyes the color of bachelor’s buttons.

My brother had the same color eyes, but on him they could look devious on account of all the shenanigans he pulled, most of which involved tricks

ordered by mail. Mother was always threatening to send Wayne Junior off to military school if he didn’t shape up. But she wasn’t serious. The fact was, nobody laughed harder at his pranks than she did.

Of course Mother wasn’t laughing at the funeral. She wasn’t crying, either. Neither was I.

I knew I should’ve cried, but I couldn’t. I didn’t feel sad. That’s the other thing about funerals: Sometimes you don’t feel sad. You don’t feel anything at all other than a sense of floating above yourself and looking down on the scene, thinking:

That’s not really me. That’s not really them.

After the service I sat with Mother and Mamaw in the backseat of a fancy black funeral car as we rode from First Baptist Church of Digginsville to the cemetery. Past the Digginsville K–12 School (“Home of the Mighty Moles!”). Past the Dig In Diner. The Donut Hut. The Crossroads Hotel, which was the only three-story building in Digginsville (population 402). Past the Graff twins, Merry and Murray, walking with their fishing poles in the opposite direction down Highway E toward Doc Lake.

A reception was held at our house after the burial. People skulked around, eating lukewarm casseroles off Chinet paper plates and talking about how won

derful my sister, brother, and Daddy all looked in their caskets.

“Wayne has never looked more handsome,” declared Mrs. Kay Beth Bowman.

“I heard between the three of them, they had five hundred broken bones,” added the dour Mrs. Nanette Toyt. “But to look at them, you’d think they’d just taken a little nap ’stead of fallen out of the sky in Wayne’s personal

air-o-plane.

”

Where I grew up, lots of people put an

O

in the word

airplane.

“Thank heaven Hattie wasn’t in the plane, too,” added Miss Savannah Phifer.

Didn’t they know my mother never flew on account of her motion sickness? Even car trips made her queasy.

“Why Wayne needed to have his own

air-o-plane

I’ll never know,” commented Mrs. Bernette Slick. She had streusel cake crumbs on her cheek. “Do you know how much an

air-o-plane

costs?”

“I betcha Wayne got a discount on it from Ozark Air Lines,” murmured the baggy-faced Mr. Bud Mosley. His wrinkled suit was covered with yellow cat hair. Pickles, Mr. Mosley’s cat, was probably wandering down Main Street at that very moment, wondering where his bed had disappeared to.

I wondered if Bud Mosley ever found someone interested in his cracked aquarium.

Why didn’t he just throw the stupid thing away? If it was cracked, it was broken

.

“Never mind what a plane costs,” blurted Mrs. Joetta Porter. “Did you see those curls on little Lilac Rose? She looked like an absolute angel. And Wayne Junior looked like a young prince. Hattie did a

lovely

job.”

“Indeed she did,” confirmed Mrs. Nanette Toyt. “Those beauty school classes Hattie took before she got married sure paid off. And didn’t she look pretty in that navy blue suit? That color complements Hattie’s black hair and fair skin so nicely.”

“I’ve

always

said,” added Miss Patrice Wood, holding up a thin finger, “that Hattie looks exactly like Ava Gardner.”

My mother was pretty, even on the day of the funeral. As for the rest of my family, I thought they looked like wax mannequins. I couldn’t understand why, weeks after the funeral, everybody was still talking about how beautiful they looked.

But that’s how Mother was hired by Danielson Family Funeral Home as a hair stylist for dead people. She was promised forty-five dollars for every corpse she styled.

“And just think, Daralynn,” Mother told me the day she got the job. “I won’t have to waste a slim dime on hair spray. A person’s hair’s not likely to get wind-blown lying in a coffin.”

I began to think of my life as a time line. Before the Crash was B.C. After the Deaths was A.D.

In my B.C. life, my mother didn’t have a job. Now in the A.D. era, Mother was going to be a hair stylist for dead people.

In my years B.C., I shared a bedroom with Lilac Rose. Now in the A.D. years, I had my own room.

For most of my life B.C., I’d been part of a family of five. Now we were a family of two—just Mother and me, plus Mamaw next door.

My entire life B.C., Mamaw ate dinner with us only on Sundays. Now she ate with us every night. But it never felt like a real dinner because we kept eating off Chinet paper plates. Mother didn’t have the energy to wash real dishes, and she didn’t trust me with the china.

After the grief casseroles tapered off, Mother lost the will to cook. So we started ordering all our food from the Schwan’s man, who delivered frozen food in

his refrigerated truck with the built-in compartments. Our weekly Schwan’s order consisted mainly of ice cream and Salisbury steak TV dinners.

I hated Salisbury steak TV dinners, both B.C. and A.D. It didn’t help that Mother served them with Schwan’s heat-and-serve Parker House rolls, which she burned every single solitary night. That’s something Mother never would’ve done B.C.

Something else Mother never would’ve done: Hired Marvin Kinser to build a breezeway. But that’s exactly what she did one month A.D.

It was just a flimsy hallway that connected the den in our house to Mamaw’s bedroom. Mother said she wanted to be able to go back and forth to Mamaw’s house without going outside, which made zero sense to me.

“What’s gonna happen just by walking next door?” I wanted to know.

But Mother didn’t answer. She was in her silk bathrobe, watching Perry Mason crack a criminal case on television—yet another thing she’d never done B.C. She’s the one who always called TV the “idiot box.”

I suspect the real reason Mother had the breezeway built was so she could wear her slippers and robe

on days she wasn’t working. That’s what Mamaw wore, too.

Mamaw’s mind started going downhill real fast after the crash. She started forgetting things—simple stuff, like how to address an envelope. Then she started acting downright silly, like she was a little girl instead of an old lady with frizzy gray Albert Einstein hair.

I knew for a fact that Mamaw was losing her mind the day she asked if she could play with my new dolls. When I said no, she began sneaking in my bedroom to steal them.

The first time she did it, I thought:

Good gosh, Lilac Rose and Wayne Junior will DIE when they find out Mamaw’s playing with dolls!

And then I caught myself. That was a B.C. thought.

Living in A.D. was going to require a whole new kind of thinking. So I surrendered myself to the unshakable truth that everything had turned terrible, and there was nothing I could do about it.

And with that thought, something inside me turned off with a click.