As Easy as Falling Off the Face of the Earth (14 page)

Read As Easy as Falling Off the Face of the Earth Online

Authors: Lynne Rae Perkins

He could not stay there for long, and as he worked his way back to a standing position, the words

pulled groin

presented themselves in his mind. The effort not to cry out caused his eyebrows to lift several inches and stretched his mouth into a cornucopia of anguished shapes. He found the bathroom. The stuff he had put his hand into was PB&J. Not so horrible. He washed it off, glancing up at his face in the mirror. Not too bad, compared to before. The eye shape was normal. Just a bruise, now.

Back in the kitchen, he knelt down to help Del.

Ow

,

he said silently, to himself. Then, despite all his noble, mighty efforts, there was Sharon, blinking, the Batman cape pulled around her shoulders.

“Oh my God, Del,” she said. “What are you doing?” Her face had a stunned expression to it, which made Ry view the scene in a new way. She was probably thinking that a couple of hours ago she had a kitchen floor, albeit one with a soft spot, and now she had a gaping hole. A huge gaping hole. That would be dismaying. He could see her point of view. Plus the pieces of what used to be her floor were piled in a trashy heap on the shores, the rim of the crater.

“The leak is fixed,” Del said calmly.

“You need to stop now,” said Sharon.

“I can’t stop,” said Del. “I’m not finished. It wouldn’t be right.”

“What do I have to do to get you to stop?” asked Sharon. She put her hands on her hips.

“I guess you could call the police,” said Del.

“Maybe I will,” said Sharon. She folded her arms across her chest.

“Tell them someone is fixing your rotten floor against your will,” said Del. Ry could tell he was enjoying himself. He kept his features still, but his eyes were twinkling.

Sharon didn’t know what to say next. She let her hands drop to her sides.

“You should go to bed,” said Del.

“How can I sleep with all this racket?” asked Sharon. Hands simulating racket.

“Shut the door,” said Del. “I’ll hammer as quietly as I can.”

“You’re not going to stop, are you?” she said. It wasn’t a question. One hand returned to her hip. The other rested against the doorjamb.

“No,” said Del. “Not yet.”

She threw up her hands and walked away. A door closed. Another door closed. Ry and Del looked at each other. Del’s smile broke out from inside into the open, full force.

“It’s just dangerous to have a hole in the floor, especially with a little kid,” he said. By way of explanation.

“I can’t believe I put my foot through someone’s floor,” said Ry. “I don’t even know her, and I come into her house…” The end of the sentence was his hand gesturing toward where the floor used to be.

Del shrugged. “It was an accident waiting to happen,” he said. “It’s actually lucky we were here. It was lucky it was you, not Miles.

“You should try to get some sleep on the couch,” he said then. “That way, when I finish this, you can drive and I can sleep. Then we can make up for the lost time.”

So Ry went out to the couch. He pulled a red fuzzy throw over himself and laid his head on a corduroy pillow. (Did you hear about the guy who fell asleep on the corduroy pillow? It made headlines.) He was becoming like a dog, he thought, that can curl up anywhere and fall asleep. After a few minutes, he found another pillow to put over his head to muffle the sawing and hammering. Because he wasn’t quite like a dog. He didn’t have a furry, floppy ear.

L

loyd was being taken somewhere in the backseat of a car. The highway was a blur; the exits were all generically named and populated with Comfort Inns, BP gas plazas, and whatnot, all with signage glowing into the night. The car left the highway for a briefly busy thoroughfare lined with car dealerships, big box stores, and fast food franchises that soon dwindled to a county road. There had been some social events, with people he didn’t know, but he didn’t feel unsafe. He was with Betty and her sister.

The car slowed and turned onto a dirt two-track. The two-track jolted and meandered haphazardly into a thicket, which thinned and heightened and spread into a woods, which dimmed into a forest.

The bumpiness of the road did not soothe a dull throbbing Lloyd felt at the back of his head. The car crept

along behind its headlights. He closed his eyes. When, after a time, the car rolled to a stop, he didn’t notice. What woke him was the clunk and squeak of the car door opening next to him, and the cool air from outside. It was falling asleep that threw him off. His recovering brain cells had not had time to regroup. Disoriented by sleep and by his skipping synapses, he looked to see who had opened his door, but the inside of the car was lit and it was dark beyond; black as ink, black as pitch. As black as night, you could say. He heard footsteps walking away in pine needles and soft earth, then a key being inserted into a lock. A door was opening, creaking lightly. He wondered if he was in danger; a memory fragment surfaced, something about a car pulling up beside him as he walked on an unfamiliar sidewalk, the apprehensiveness he felt as he turned to see who it was. He wondered whether he shouldn’t disappear silently into the darkness, the pitchy inky night. While he had the chance, he swung his feet out and down to the ground. He stood up and stepped out of the circle of light.

“Where did he go?” said Betty to her sister, Ruth.

They were twins, but they had different dispositions. Betty was cheery and friendly, Ruth was more on the cranky side.

They were searching through the dark woods with

flashlights, trying not to get lost themselves.

“I guess I shouldn’t have brought him there,” said Betty. “It was probably confusing with all those people. I just thought—”

“If you would mind your own business,” said Ruth, “you’d save yourself a lot of trouble. Not to mention other people.”

Oh, shut up, Ruth, thought Betty. “I hope he’s not lying facedown in a ditch somewhere,” she said.

Which, oddly enough, Lloyd was. Five minutes into his escape, his head cleared, and he remembered: Betty, the neighbor. The family cabin.

Feeling foolish, he turned to go back. He could see the tiny windows lighting up in the cabin in the distance. He felt for the ground with his feet and held his hands in front of him to fend off unseen branches. What tripped him up was a half-fallen sapling, at shin height. He came up against it and went down like a mousetrap snapping shut. He had just enough time to put out his arms and break his fall. Thus fracturing his collarbone. And one of his wrists.

So, technically, there wasn’t a ditch, Ruth might have said.

To which we say, Oh, shut up, Ruth.

H

is sleep was not quite as restful as it might have been had he slept next to a radio stuck between stations, or under the dripping pipe on the kitchen before Del fixed it. His dreams made their way over a soggy, wafer-thin floor littered with obstacles. Phones were ringing in faraway rooms. He needed to find them and answer them, but the noise he had to move through made it hard to figure out where they were. The phones would tell him what it was that he was supposed to do. Time and again he was on the verge of finding one when it turned out to be something else. Chirping birds in a cage. An alarm clock. A microwave oven announcing that the burrito was warmed up now. He took the burrito out of the microwave. The microwave was in a gas station convenience store. Someone grabbed his arm and said,

“Hey,” and he realized that the burrito belonged to that person. It was Del. The burrito belonged to Del. Del was shaking his arm gently, and he opened his eyes and it really was Del.

“I think we better get going,” said Del.

You have to be asleep for someone to wake you up, so Ry must have slept, but he felt woozy and unrested. He eased up to a sitting position and leaned his face into his hands, not ready for the lamplight Del had switched on. After an indeterminate amount of time, he pushed his way up into a standing position. The swath of pain that flashed through his groin as he did so went a long way toward waking him up more thoroughly. He walked stiffly toward the kitchen and squinted into its fluorescent brightness.

It was tidy as a pin. Whatever that means. The heap of rubbish had been removed, and in front of the sink was a sturdy, neatly built mosaic of pieces of wood Del had found in the basement. They were different colors. It looked kind of cool, really. Like if people saw it, they would want one, too. Ry went over and stood on it. Solid as a rock. Then he stepped back and pulled open the cabinet door. A similarly crafted level surface held up the bottles and buckets and whatever else was underneath there.

“We should go,” Del said again. He looked tired, but happy. They turned out the light in the kitchen and the lamp in the living room and stepped out the front door and pulled it shut with a quiet click. The screen door banged lightly behind them. The world had freshened up overnight: the air was cool and moist, a couple of birds sang back and forth, a new sky had barely begun its glimmering over at the horizon.

Del climbed behind the wheel and Ry thought maybe he had decided to drive after all. But he only navigated the twists and turns to the on-ramp, then pulled over.

“I probably won’t sleep more than a couple of hours,” he said. “We’re on this road for quite a ways now, so all you have to do is stay on it.” He crawled over the seat into the back. Ry slid over into the driver’s seat. He fastened his seatbelt and heard Del’s boots come off and land on the floor, heard Del sliding down into his bag and arranging himself.

“Wake me up for breakfast,” Del said. So Ry put the Willys in gear and headed up onto the highway.

I

t was exhilarating to be alone at the helm. At first it was enough just to be driving down the highway. The time of day itself was kind of amazing. It wasn’t often that Ry was doing anything useful at this hour. Not that many other people were either, apparently; traffic was sparse. He felt himself one of a small brotherhood: The Few. The Proud. The Awake.

The sun rose orange from the edge of a clear sky and the countryside went all golden and emerald around him, with houses and barns set here and there catching the light and casting deep westerly shadows.

And then it was regular morning. Still nice, but less spectacular. Feeling an urge to put something in his mouth, Ry took a sip of his beverage from the night before, a blend of root beer, Sprite, Hawaiian Punch, and

Coke. It tasted pretty lousy. It was better when it was fresh and had carbonation. Or maybe it was an evening/morning thing. He tried a sip of Del’s leftover beverage, a coffee. Bleahh. Even worse. He would have to hold off for a while.

It wouldn’t be bad to have the radio on, though. He could play it softly. His eyes dropped momentarily down to the dashboard. Like many other parts of the Willys, the radio had been recruited from some other career and installed in a way that was obvious and made perfect sense to Del. Anyone else had to look at it for a minute or two and experiment a little. Open the mind to new possibilities. Think of all the ways a thing might be switched on.

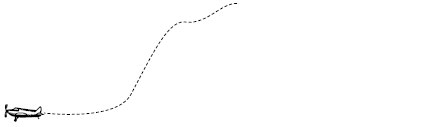

I’m not saying that Ry didn’t keep glancing up to make sure he was on the road, staying in his lane. But he wasn’t looking at signs. He didn’t think he had to. They were staying on the same road. For quite a ways. But sometimes, staying on the same road means you have to choose the left part of a Y or take an exit to the left side of the road. Sometimes both, in quick succession. Sometimes you have to look at the signs to get where you want to go.

He found a decent station and settled back in. The

highway had widened—it had six lanes now—and it was getting busier. A lot of trucks barreled past and moved in and out of lanes behind him and ahead of him. The trucks were like planets with their own gravity; he could feel his own course being altered when they roared by. Too close for comfort. He heightened his powers of concentration. It was like Need for Speed. In Sensurround. He was glad he had turned on the radio. Tunes made him feel braver. More confident.

You can get used to anything. Before long Ry was unfazed by the vehicular tonnage careening all around him. He found the Flow. Serenely, his eyes took in his surroundings in a video game kind of way. In the present tense. Respond to what pops up in front of you.

It popped into his head that it was surprising that they weren’t driving more into the sun, since they were heading southeast. The sun was actually behind them. They were heading west. But roads often twist and turn. Though this one seemed straight enough.

What felt good was, he was doing what needed to be done. He wasn’t waiting for someone else to do it for him. It’s true that he couldn’t be doing it without Del, but he was doing his part, too. They were going to figure it all out. Find out the facts. They were on the way.

He drove under one of those overhead signs that tell which lane you should be in depending on where you are going. He looked at this one and couldn’t help noticing that none of the choices applied to him, to them, to their plan. And then suddenly the road was splitting into three strands, each veering off in a radically different direction—right/left, up/down, over/under—lanes of traffic coming from every which way, and Ry had no idea where he should go.

He rode the traffic like a wave, deciding that survival was the main thing, but looking for clues, for the sign with his name on it. He was supposed to stay on the same road. Maybe this was just part of it. But the number wasn’t right. The cities weren’t right.

Calmness had left him, but he drove on. He couldn’t exactly stop. Not in the middle of the spaghetti. His road dipped under and curved around and shot out high above a river, and then as quickly as he had entered the tangled knot he was out of it. Driving through the countryside. The wrong countryside, he was pretty sure.

Salvation came in the form of a highway rest area. He pulled off just so he could stop for a minute and think. Del’s voice came from behind him, asking sleepily if it was time for breakfast.

“No,” said Ry. “Not yet. I just have to…”

He got out of the Willys, leaving Del to fill in the blank. Walking inside the building, he glanced to his right and saw the giant map. The Blessed Map. The difference between this map and Del’s road atlas was that this one had the magical You Are Here arrow. Fortunately, the map was large enough to include not only Where He Was, but Where He Was Supposed To Be. That was not shown by an arrow, but he found it. He didn’t know how he had strayed. He was just glad he could find a hypotenusal route to get him back there that avoided the splitting, weaving rat’s nest of roads he had just clenched his way through.

He zipped to the restroom, then returned to the map and studied it again. He memorized what he had to do. There were three parts to it. Three road numbers, plus three town names where he made changes. He made up a singsongy rhyme to help him remember. It had the three parts, then it went, uh-huh, oh yeah, or la la la or something. Some beats to finish it off.

When he started up the Jeep, Del’s voice asked, “Are we there yet?”

Ry said, “No, go back to sleep.” Realizing he had been abrupt, he added, “I mean, I think we should go a little farther.”

He made his way back into the stream of traffic. The

first change came up almost right away. He guided the Willys into the lane under the desired route number and curved smoothly to the south while the other lane continued stubbornly, misguidedly west. The rhyme song shrank to two main parts. More filler. La la la la la, shaboom, shaboom.

He didn’t want Del to know he had messed up. He didn’t want Del to save him this time. He wanted to fix it himself. He didn’t have any clear idea of how long he had been going the wrong way or how long it would be till they were right again. It was twelve miles to the next change, according to the sign. A few eons passed, then it was five miles. One mile. And now, here was the exit. Here was the road that would lead them to the right road. This road was a secondary road. It rambled along from one tiny town to another. It had potholes. It had traffic lights.

Ry aimed for maximum smoothness. He tried to smoothly swerve around the potholes. Some of them were canyons that trenched across both lanes. Sometimes the abundance of them didn’t allow for weaving. You just had to jolt through as damage-free as possible. He eased to a halt as smoothly as he could when the lights went red and, as smoothly as he could, shifted back up to speed when they went green.

He watched for signs telling him how far he still needed to go. He knew he was running out of time, if he wanted his goof-up to remain undiscovered. More potholes, a spattering of them. Bada boom. Shaboom, shaboom, la la la boom. It was an anti-lullaby. An unlullaby, like machine-gun fire.

And another intersection: Stop. Wait. Start.

A newly paved stretch of asphalt appeared and slipped itself beneath the wheels. The sudden quiet was velvety; it was like church. A sign rose up and announced that only one mile remained until the elusive, conclusive junction. And then there it was. The on-ramp curling gracefully ahead and to the right. Ry put on the turn signal. Victory flowed through his veins. He had done it. He had found his way back. Choirs of angels gathered on pinheads and sang. Del would never know. La la la la la la la.

“It looks like we’re almost out of gas,” Del said. Ry flew up out of his skin, bumped his head on the ceiling, and almost went off the road. That is, two of those things seemed to happen and one of them did happen.

“We’d better get some before we get back on the highway,” said Del. He was leaning over the back of the passenger seat. How long had he been there? Ry stayed on the road but missed the ramp. He made the sound

of raspberries at the exit, the road ahead, his doomed effort.

“Well, we won’t get very far without it,” Del said. “Look, there’s a place right there. And we can get breakfast.

“Where are we, anyway?” he asked. “Why are we off the highway?”

And Ry realized that maybe Del still didn’t know what had happened. He made a couple more raspberries, the sound of a motor puttering along.

“Detour,” he said. “I think there was an accident.”

He was just summarizing. It was one way of putting it.