And the Band Played On (14 page)

Read And the Band Played On Online

Authors: Christopher Ward

‘Let me say first of all that I was commissioned to bring aboard all the bodies found floating,’ he told the reporters gathered around him. ‘But owing to the unanticipated number of bodies found, owing to the bad weather and other conditions, it was impossible to carry out instructions, so some were committed to the deep after a service conducted by Canon Hind.’

Then came the controversial bit:

‘No prominent man was recommitted to the deep. It seemed best to embalm as quickly as possible in those cases where large property might be involved. It seemed best to be sure to bring back to land the dead where the death might give rise to such questions as large inheritances and all the litigation.

Most of those who were buried out there were members of the

Titanic

’s crew. The man who lives by the sea ought to be satisfied to be buried at sea. I think it is the best place. For my own part I should be contented to be committed to the deep.’

Larnder’s remarks did little to ease the pain or provide comfort to those whose loved ones had been recovered by the

Mackay-Bennett

but not brought back to Halifax. The

New York Times

reported next day that ‘the whole colony is stirred by an immense pity that it had to be, and not a few are wondering if it really had to be, a wonder fed by the talk of some of the embalmers . . . The large majority [of those buried at sea] were either members of the

Titanic

’s crew or steerage passengers.’ The publisher of

The Casket

, the official organ of undertakers in North America, condemned in an issue published some months later ‘the barbarous use of the ocean’s depths as a cemetery’.

What Larnder did not reveal was that it had been his intention to bury many more bodies at sea; even as the

Mackay-Bennett

was approaching Halifax the crew were unstitching canvas body bags and removing iron bars from them.

Later that afternoon, Captain Larnder, having recovered his composure, made his final entries of the voyage in the

Mackay-Bennett

’s log:

10 a.m. Commenced discharging bodies, total 201 [

sic

].

1.35 p.m. Police patrol wagon took away personal effects. Cast off and proceeded to CC company wharf. Fast alongside cc wharf.

2.00 p.m. Finished for the day.

The discharging of bodies did not go quite so smoothly as Larnder’s log suggests. He might also have added that he had sailed into a storm on dry land.

Even before the

Mackay-Bennett

had embarked on its morbid mission, extensive and efficient arrangements were being made in Halifax to receive the dead. The White Star Line, anticipating an avalanche of bodies, ordered 500 coffins from Ontario and commissioned Snow’s to take charge of the processing of the dead. Snow’s recruited nine undertakers and forty embalmers from Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island, including two sisters who would embalm the bodies of women and children recovered. The Mayflower Curling Rink on Agricola Street was identified as the best facility in the city to serve as a temporary morgue. The ice kept the building chilled and the rink provided more than enough space to lay out the bodies for identification and embalming. Joiners set to work making tables wide enough to take three coffins or bodies side by side. The photography studio of Gauvin & Gentzell was engaged to take photographs of the dead that might later assist in identification, George Gauvin agreeing to take the photographs himself. The White Star Line also negotiated with the city to purchase a large number of burial plots at Fairview Lawn, Mount Olivet and Baron De Hirsch cemeteries.

Everything had been thought of . . . except the needs and feelings of the relatives, loved ones and friends of those who had died. Many of them – those who could afford to, those who lived near enough to come – had travelled to Halifax to await the

Mackay-Bennett

’s arrival. They included

Titanic

survivors, some still suffering from frostbite, who had come by train from New York to identify and claim the bodies of their lost companions. The distressed visitors found a city in mourning, flags at half mast, shop windows draped in black and horse-drawn wagons clattering through the streets loaded with coffins. Their grief was exacerbated by reports of transatlantic liners slicing their way through bodies and wreckage without stopping. Mail ships had been advised to give the area a wide berth but ships continued to report sightings of bodies and wreckage. A party of Scandinavian immigrants en route to Minnesota related an incident ‘so heartbreaking and ghastly’ that it was brought to the attention of President Taft. ‘In several instances,’ the immigrants reported, ‘bodies were struck by our boat and knocked from the water several feet into the air.’

Lurid newspaper accounts included an interview with a First Class passenger on the Bremen, who reported seeing the body of a woman in her nightdress, clasping a baby to her breast. Close to her was the body of another woman, her arms locked around the dead corpse of a shaggy dog. Other passengers saw the bodies of three men in a group, all clinging to a chair. Floating by just beyond them were dozens of bodies, wearing lifebelts and clinging desperately together as though in their last struggle for life. The entire surface of the ocean around them formed ‘a wreath of deckchairs and other wreckage’.

The phrase ‘it is impossible to imagine . . .’ is one that recurs time and again in the accounts of people who survived the sinking of the

Titanic

or were involved in the subsequent recovery operation. New York received the survivors and saw many scenes of joy, reunions and relief in the week following the sinking. But the shadow of death fell across Halifax and darkened in the two weeks between the sinking of the

Titanic

and the return of the

Mackay-Bennett

. It is impossible to over-estimate the grief that enveloped the ‘City of Sorrow’.

While the

Mackay-Bennett

was still at sea, the White Star Line prolonged and aggravated the agony by withholding information on the identities of the dead whose bodies had been recovered. But the news blackout did not extend to VIPs, such as Jacob Astor. The official excuse was the difficulty in transmitting so many names by Morse code, but the reality was that the White Star Line was reluctant to admit that almost half the bodies that had been identified had already been buried at sea and would not be returning to Halifax. Of the 1,497 who had died only 306 bodies were recovered by the

Mackay-Bennett

and a third of them had been buried at sea.

Within a day of the

Mackay-Bennett

arriving at the scene of the wreck, newspapers in Halifax were drip-feeding information about the number being recovered and speculating as to their identities, with no information coming from the White Star Line itself. Under pressure from the bereaved, most of them American, who had arrived in Halifax in the hope of returning home with the body of a loved one, the Mayor convened a meeting at which a ‘mourners’ committee’ was formed, chaired by the former US Consul-General James Ragsdale.

White Star Line agents responded by opening an ‘information bureau’ at the Halifax Hotel in Hollis Street three days before the

Mackay-Bennett

’s arrival. The first and only bulletin of the day was a wireless message received from the

Mackay-Bennett

. It read: ‘Confirm bodies of Astor and Strauss on board. Due Monday with 189 [sic] bodies.’ This was the first admission that more than 100 bodies had been buried at sea. It reduced many relatives who read it to tears and the revelation that the only two bodies identified so far happened to be those of multi-millionaires added anger to their grief. A class system in life had been replaced by a super-class system in death.

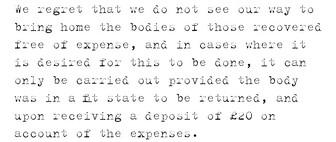

The second White Star bulletin of the day provoked even greater outrage:

When bodies are ready for shipment, friends may take them on the same train in the baggage car on payment of the regular first-class fare . . . bodies may also be sent by express on payment of two first-class fares. The offices of the Canadian Express Company are prepared to render every assistance.

Families from Europe who made enquiries about arrangements for transporting the bodies of loved ones back home were told by the White Star Line that ‘normal cargo rates would apply’. Sarah Gill, the widow of Second Class passenger John Gill, whose body was recovered by the

Mackay-Bennett

, received a letter from the passenger department of the White Star Line written on 3 May. It said:

The White Star Line offered Mrs Gill their ‘profound sympathy’ for the ‘terrible calamity’ but regretted that the company could not be held responsible for the results of the ‘unfortunate accident’. As it turned out, the White Star Line’s hard-hearted response to the widow was quite unnecessary as Mr Gill, a chauffeur to a vicar, had been buried at sea a week earlier. The letter was sold at auction in 2002 for £5,500.

Fortunately the Astor family could afford to make their own arrangements. Colonel Astor’s son Vincent, having been alerted by the White Star Line a week earlier that his father’s body had been recovered, had already arrived in Halifax in his father’s private train, the ironically named

Oceanic

. He was accompanied by the family lawyer, Nicholas Biddle, and the captain of his father’s boat, Richard Roberts. The

Oceanic

’s three luxury carriages were shunted to a siding in North Street station, where they remained with Vincent living on board, until his father’s coffin was ready to be transported to New York to be interred in the Astor family vault. In an adjoining siding stood another private train, sent by the Grand Trunk Railway to take the body of its president, Charles Melville Hays, to Montreal.

Vincent’s first call on arriving in Halifax was to the funeral parlour at 90 Argyle Street of John Snow, father of John R. Snow Jnr the undertaker on the

Mackay-Bennett

. Vincent chose an appropriate casket and floral display to be mounted on the coffin during the rail journey to New York. At a meeting of mourners the next day at the Halifax Hotel, the White Star Line’s representative Mr Jones said he had received information that ‘certain gentlemen’ had tried to bribe undertakers and that the White Star Line ‘would not stand for it’. Despite this assurance, the first death certificates to be issued would bear the names of Colonel J. J. Astor and Isidor Strauss, the millionaire retailer and founder of Macy’s on Fifth Avenue. Their bodies would also be the first to leave Halifax.

But the American millionaires were not the first corpses to leave the

Mackay-Bennett

. That honour was accorded to the men lying in the ice – most, if not all, Third Class passengers or crew. They included my grandfather Jock and his fellow bandsmen Wallace Hartley and Nobby Clarke. ‘They presented such a gruesome sight that it would be most impossible to picture,’ wrote a reporter in the

Daily Echo

. Many of them were naked, the rest were in their underclothes, their arms and legs frozen grotesquely so that they looked as if they were gesticulating or kicking at their moment of death. They were carried off the ship on stretchers and loaded on to handcarts, covered with tarpaulins, and transported at speed and with embarrassment to the Mayflower Curling Rink. It is said that the shoulders and hips of some of these dead had to be broken or dislocated to fit them into the narrow coffins.