And the Band Played On (5 page)

Read And the Band Played On Online

Authors: Christopher Ward

Mrs Mackay, wife of the popular millionaire president of the company, had christened the ship when it was launched the previous year in Glasgow, and had taken a particular interest in the interior design when it had been fitted out. The captain’s cabin, situated in a deckhouse forward of the poop, was unusually comfortable and on either side of the saloon on the main deck were state rooms for cable engineers, electricians or passengers. One of these, a large cabin handsomely panelled in mahogany, was reserved for the use of Mr Mackay and Mr Bennett. It was here, no doubt to his immense relief, that Canon Hind was shown after boarding the ship.

The

Mackay-Bennett

owed its name and existence to the brilliant business partnership of Mackay and Bennett, who had founded the Commercial Cable Company in 1884 to compete with Western Union’s virtual monopoly on transatlantic telegraphy. Bennett was a madcap entrepreneur who had financed Henry Stanley’s expedition in Africa to discover Dr Livingstone. After taking over management of the

New York Herald

from his father he had moved to Europe to build a newspaper empire there, with London and Paris editions of the

Herald

made possible by the recently developed technology of undersea cables. The

Mackay-Bennett

was built specifically as a cable repair ship to maintain CCC’s undersea cables, which remained in use carrying telegraphic traffic until 1962.

In Halifax the

Mackay-Bennett

was particularly well regarded and its captain was as popular as he was well respected. Such reputations were not easily gained in the tough shipping community of Halifax. Reporters boarded the ship before its departure from Halifax, the

Evening Echo

publishing a large picture of the ship taken shortly before it sailed. The accompanying report said that

. . . in the Mackay-Bennett the White Star Line have secured a ship especially well fitted for the task set her. Her commander, F. H. Larnder is a thoroughly trained navigator, careful and resourceful and he has under his command a crew of officers and men that might be classed as picked.

It was indeed good fortune for the White Star Line – and for the relatives of the dead whose bodies were recovered – that the

Mackay-Bennett

was available for charter by the White Star Line. Its cable-laying design and specialist equipment were exactly what was required for the job in hand: that is to say, retrieving dead bodies from the water. It was well equipped with grapnels and grappling hooks and manned by crew who knew how to throw them accurately and retrieve them quickly. For heavier weights there was a powerful capstan and two horizontal steam winches. Because of the nature of its work, it was a ship designed for drifting, with a rudder at each end of the ship for manoeuvring and two large cutters for working outside the ship. Twin generators drove powerful lamps, which allowed the ship’s crew to work at night.

Larnder had sailed the

Mackay-Bennett

out of Halifax harbour a hundred times before. As always, he took the easterly channel past George’s Island, passing McNab’s Island on the port side. Even as the fog thickened he could make out the shapes of the familiar landmarks slipping past them, their names reflecting Halifax’s rich history: Ferguson’s Cove, Sleepy Cove, Sandwich Point, then Herring Cove where a pod of dolphins joined them, racing alongside the bow, leaping and diving, their welcoming grunts clearly audible above the chugging of the

Mackay-Bennett

’s engines.

The graceful escort raised Larnder’s spirits. The proximity of the coffins on deck had made him morbidly preoccupied with the gruesome task ahead. The dolphins reminded him that for the moment anyway his priority must be the living, not the dead, the safety of his crew put above all else. The

Mackay-Bennett

had cast off less than an hour ago but already his wireless operator had brought warnings of three more sightings of hazards directly in the course: icebergs, pack ice and ‘growlers’ – small icebergs floating just below the surface but no less deadly and almost impossible to see.

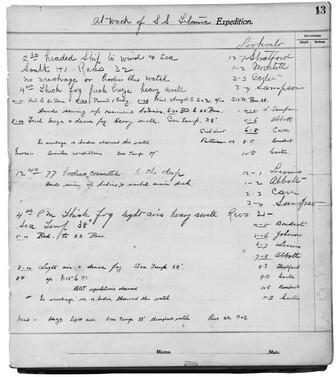

Larnder had already decided there would be a round-the-clock series of one-hour watches for ice and, later, for bodies. Bouderot had taken the first watch. Now Larnder noted his order in the deck log – Bouderot noon to 1 p.m., Sampson 1-2, Stratford 2-3, Carter 3-4, Patterson 4-5, Abbott 5-6 and 6-7, Carr 7-8 – and then Bouderot followed by Sampson again.

The ghostly shape of the lighthouse on Devil’s Island loomed up, marking the south-east passage out of Halifax. Through the fog they could barely see Maugher’s Beach, better known as ‘Hangman’s Beach’, once a popular site for hanging mutineers and leaving them there as a warning to passing crew. From here it was a straight run to the open sea past Portuguese Cove and the Chebucto Head lighthouse. Now they were in open water, leaving behind them a low slip of land and the Sambro Island lighthouse. The oldest lighthouse in North America, it burned brightly for years fuelled by whale oil but around 1900 was converted to burn kerosene. It had been painted with red stripes the previous summer to make it more visible in the winter snow.

The

Mackay-Bennett

was three days’ sailing away from its destination but there was still much to be done and no time to be wasted. The ship’s carpenter made an operating table for the undertaker which was ‘strong enough to take a 20-stone man’, according to Mr Snow’s instructions. The undertaker also requested the carpenter to make three screens so that he could work in privacy away from curious eyes.

Other hands were put to work cutting up sailcloth to make small duck bags. This was the purser, Frank Higginson’s idea. When the bodies were brought aboard, each corpse would be given a sequential number, a label bearing the number tied to the body. A description of each person, and their identity if known, would be entered in a book against the number. Any possessions found on their body would then be put in a duck bag, numbered by stencil, so that personal effects could be returned to the correct next of kin. At least two crew members would help in this process, in the presence of either Mr Snow, the purser Mr Higginson, or the ship’s surgeon, Dr Thomas Armstrong, to prevent theft or other irregularities. The clothes of the dead would be removed, bagged separately and stored in the ship’s hospital. When the

Mackay-Bennett

returned to Halifax the clothes were first taken to the mortuary to assist identification, and then burned to prevent them falling into the hands of ghoulish souvenir hunters. This system of numbering the dead proved to be so successful that it was adopted to identify the fatalities – nearly 2,000 of them – after the catastrophic explosion of an ammunition ship that ripped Halifax apart in 1917.

For the next two days Captain Larnder’s log recorded only the barest of facts: wind, weather, sea temperature, names of lookouts, tasks undertaken – ‘hands washed decks, etc.’ The weather was deteriorating fast, the temperature dropping. As the

Mackay-Bennett

approached the area where ice had been reported, Larnder doubled the watch. At the same time he gave the order to increase the men’s daily rum ration to keep their spirits up. When the ship was at sea, it was customary for the Chief Steward to bring a pail of English rum at 6 p.m. every evening and dispense 3-4 ounces into each man’s drinking mug. From today, they would get eight ounces. Larnder was a captain who knew how to get the best out of his crew.

On Saturday 20 April Larnder noted in his log that a lifebelt was sighted and that he lowered a cutter to retrieve it, but the lifebelt was found to belong to a ship from the Allan Line. The same day, two messages were sent from the

Mackay-Bennett

via the Cape Race radio station to Ismay at the offices of the White Star Line in New York. The first message reads: ‘Steamer

Rhein

reports passing wreckage and bodies 42.10 north, 49.13 west, eight miles west of three big icebergs. Now making for that position. Expect to arrive 8 o’clock to-night.’ The second tells Ismay, ‘Received further information from (steamship)

Bremen

and arrived on ground at 8 o’clock p.m. Start on operation tomorrow. Have been considerably delayed on passage by dense fog.’ The

Mackay-Bennett

hove to for the night to begin operations at first light.

But nowhere in the log does Captain Larnder report that he has been communicating with Bruce Ismay, who was now safe in New York where the

Carpathia

docked on the evening of 18 April. It was as a result of receiving this information that Mr Ismay issued the following statement through the White Star Line’s office in New York:

‘The cable ship

Mackay-Bennett

has been chartered by the White Star Line and ordered to proceed to the scene of the disaster and do all she could to recover the bodies and glean all information possible. Every effort will be made to identify bodies recovered, and any news will be sent through immediately by wireless. In addition to any such message as these, the

Mackay-Bennett

will make a report of its activities each morning by wireless, and such reports will be made public at the offices of the White Star Line.

The cable ship has orders to remain on the scene of the wreck for at least a week, but should a large number of bodies be recovered before that time she will return to Halifax with them. The search for bodies will not be abandoned until not a vestige of hope remains for any more recoveries.’

Below deck, one of the cable engineers, Frederick Hamilton, had been keeping a diary with more colourful detail including wireless encounters with several passing ships. The original of the diary is in the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich.

April 19th: We spoke to the

Royal Edward

by wireless to-day, she lay east of us, and reported icebergs, and growlers . . .

April 20th: French liner

Rochambeau

near us last night, reported icebergs, and the

Royal Edward

reported one thirty miles east of the

Titanic’s

position. The

Rhine

[sic] passed us this afternoon, and reported having seen icebergs, wreckage and bodies, at 5.50 p.m. The

Bremen

passed near us, she reported having seen, one hour and a half before, bodies

etc.

This means about twenty-five miles to the east. 7 p.m. A large iceberg, faintly discernible to our north, we are now very near the area were [sic]lie the ruins of so many human hopes and prayers. The Embalmer becomes more and more cheerful as we approach the scene of his future professional activities, tomorrow will be a good day for him.

Early the next morning, Sunday 21 April, the

Mackay-Bennett

, having covered 669 miles since leaving Halifax, came upon an expanse of wreckage including an overturned lifeboat and dead bodies. Larnder cut all engines and ordered a cutter to be lowered. His log records the event without emotion and with few facts: ‘Drifting. Wind WSW, force 4. Lat 41.59N, 49.25W. Picking up bodies. Logging icebergs, Considerable swell.’ Later he described the scene as ‘like nothing so much as a flock of sea gulls resting upon the water . . . all we could see at first would be the top of the life preservers. They were all floating face upwards, apparently standing in the water.’

Hamilton’s diary entry that day provides an equally dramatic picture:

April 21st: Two icebergs now clearly in sight, the nearest is over a hundred feet high at the tallest peak, and an impressive sight, a solid mass of ice, against which the sea dashes furiously, throwing up geyser like columns of foam, high over the topmost summit, smothering the great mass at times completely in a cascade of spume as it pours over the snow and breaks into feathery crests on the polished surface of the berg, causing the whole ice mountain, which glints like a fairy building, to oscillate twenty to thirty feet from the vertical. The ocean is strewn with a litter of woodwork, chairs, and bodies, and there are several growlers about, all more or less dangerous, as they are often hidden in the swell. The cutter lowered, and work commenced and kept up continuously all day, picking up bodies. Hauling the soaked remains in saturated clothing over the side of the cutter is no light task. Fifty-one we have taken on board today, two children, three women, and forty-six men, and still the sea seems strewn. With the exception of ourselves, the bosun bird (a pelican-like seabird also known as the Tropicbird) is the only living creature here.