And the Band Played On (7 page)

Read And the Band Played On Online

Authors: Christopher Ward

But Jock’s

disappearance

– he couldn’t yet bring himself to contemplate the word death – had distressed and unsettled him, the roller-coaster of conflicting news raising, then dashing, his hopes.

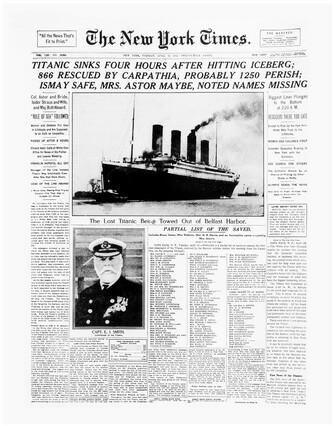

In the two days that had passed since the

Titanic

had sunk, Andrew Hume had still received no word of what had happened to his son. His telegrams to White Star Line offices in Liverpool, Southampton, London and New York had gone unanswered. His local police station had referred him to the Foreign Office, who referred him back to the White Star Line. His visit to the offices of the

Dumfries & Galloway Standard & Advertiser

had yielded no information, but had led instead to a request by the editor for some background information on Jock’s life for an obituary in next week’s edition.

Meanwhile, the Revd James Strachan from the Congregational Chapel in Waterloo Place, where Jock had worshipped, called to express his condolences. These premature presumptions of his son’s death annoyed and distressed Andrew. So far as he was concerned, Jock was alive until proven dead.

Andrew felt he was getting nowhere in Dumfries and decided he would confront the White Star Line in person. He was not alone in this. All over Britain anxious relatives and friends were besieging White Star Line offices in Liverpool, London and Southampton, demanding news of their loved ones. More than 700 of the

Titanic

’s crew had come from Southampton and hundreds of distraught family members staged angry protests outside White Star Line offices in the days after the tragedy. In London, crowds stormed the White Star Line offices in Cockspur Street, just off Leicester Square, shouting, ‘Murderers!’

Although the

Titanic

was built in Belfast and sailed from Southampton, she was registered in Liverpool – then still the British Empire’s leading sea port – and carried the name of the city across the full width of her stern.

It had been Andrew’s original intention to demand to see the chairman, the rich and famous J. Bruce Ismay, but newspaper reports had revealed that Ismay himself had been a passenger on the

Titanic

and might also be missing. Andrew drew some comfort from this: if they were searching the North Atlantic for their chairman, there might be more chance of finding Jock.

On his way to Dumfries station, Andrew called at McMillan’s newsagent’s shop where he first scanned all the papers, looking for any mention of the band, then bought the

Dumfries & Galloway Standard

. As it was printed locally, today being one of its two publication days, Andrew hoped the

Standard

might have the most up-to-date report. A pompous editorial on page two suggested that the

Standard

knew nothing, either.

A calamity involving a loss of life without parallel in the maritime archives of Great Britain occurred on Sabbath night when the latest built and most magnificent of the greyhounds of the Atlantic was engulfed on her maiden voyage. Only the Miracle of Marconi prevented it from being added to the long catalogue of unexplained mysteries of the deep.

But a report on another page reported that Jock was among those missing adding that ‘no news has yet been received as to whether Mr Hume is amongst the survivors’.

The national newspapers confirmed in more vivid prose the most pessimistic reports of the tragedy: that nearly 1,500 had lost their lives, with ‘only 868 people saved’. The news that ‘Mr Bruce Ismay is among those rescued’ brought no encouragement to Andrew Hume. He wished him dead.

Andrew could not know it as he boarded the train at Dumfries but White Star Line officials in Britain, and to a lesser extent in New York, knew very little more than what they were reading in today’s newspapers. The

Carpathia

had not yet reached New York with the survivors and no official statements had been received from the ship, Bruce Ismay having ordered a highly selective news blackout. Indeed, a misunderstanding about the

Carpathia

’s destination had led White Star Line officials in New York to despatch a train urgently to Halifax, where they thought the survivors were being taken, to bring them back to New York.

Andrew bought the

Daily Sketch

to read on the train, as its coverage seemed the most comprehensive and up to date. He read of crowds waiting outside the White Star Line offices in Southampton: ‘Women with babies in their arms, their cheeks pale and drawn and their eyes red with weeping, have stood for hours reading and re-reading vague messages of the disaster which the company had posted up.’ The mayor of Southampton had expressed the view that ‘only two per cent’ of those saved would be members of the crew.

Andrew took the same rail connections from Dumfries to Liverpool that Jock had taken a week earlier. Liverpool was a city he knew well and from Lime Street he headed briskly towards Church Street, which would lead him to the White Star Line’s imposing offices at 30 James Street on the corner of the Strand.

Everywhere Andrew looked, flags were flying at half mast and as he approached the building Andrew also became acutely conscious of the sky darkening, adding to his general feeling of foreboding and gloom. He wondered for a moment if he was going mad or about to faint. Birds were flying in ever-decreasing circles, colliding with each other on their way up or down their spiral. People were standing around in groups, jabbing their fingers at the sky and shouting to one another, some with their fists to their eyes as if holding binoculars, others holding cardboard boxes over their heads. A party of schoolchildren were staring at the sky through pieces of smoked glass. A group of a dozen blind men were staring at the ground listening intently to their escort who was addressing them while pointing upwards. Andrew caught the word ‘phenomenon’ several times and the blind men nodded knowingly, to acknowledge their understanding of what they were not witnessing.

He told his family later that the scene reminded him of Bedlam or, to be more precise, the Crichton Royal Lunatic Asylum in Dumfries where his father worked as a ward orderly in the final years of his life. It was as if the world were coming to an end and the nearer Hume got to the White Star Line building, the darker the sky became.

In one sense, Andrew Hume’s world

was

coming to an end. For the first time he was facing up to the reality that his son had almost certainly died. It was hardly surprising that he had completely forgotten about the event that astronomers had been eagerly awaiting, namely a solar eclipse at 11.17 a.m. on 17 April 1912, the very moment Andrew Hume arrived at his destination. He was not a superstitious man but he rightly saw the darkening sky as a terrible omen. Newspapers next day would describe it as ‘the

Titanic

eclipse’, a name that would eventually find its way into astronomers’ reference books.

Albion House, the Liverpool headquarters of the White Star Line, is to architecture what the

Titanic

was to transatlantic liners: a grandiose monument to the ego of Thomas H. Ismay, founder of the White Star Line. As if launching extravagant steamships was not enough, Thomas Ismay also liked to use bricks and mortar to make an impression. In 1882 the shipping magnate commissioned the London architect Richard Norman Shaw to build him a mansion, enormous even by Victorian standards, called Dawpool at Thurstaston on the Wirral in Cheshire. The house was ‘an unhappy mixture of sandstone, ivy and old English revivalist architecture’ according to his biographer, Paul Louden-Brown, author of a book on the White Star Line. Dawpool proved difficult to run, ‘lacking hot running water and cold with fireplaces that smoked whichever direction the wind blew’. The lack of hot water was one of Ismay’s petty meannesses, rather than an engineering oversight: he could not see the need for expensive piping when servants were perfectly able to run up and down stairs with jugs of hot water from the kitchen. Later, the house proved to be unsaleable and after several unsuccessful attempts to demolish it manually, Liverpool Council had to resort to high explosives to reduce it to rubble.

In spite of the problems with his house, Ismay awarded Shaw the contract to build the White Star Line’s new headquarters in Liverpool twelve years later. Shaw shamelessly copied the design of red brick and granite that he had used to convert an opera house into what became New Scotland Yard, the former headquarters of the Metropolitan Police, on London’s Embankment. Like the shipping line’s steamers, Albion House was designed to impress and even today, unoccupied and boarded up as it is, the building remains an imposing landmark in the city, dramatically positioned at the bottom corner of James Street next to the Strand, overlooking the River Mersey.

However grand from the outside, its office accommodation was austere, even for directors. Thomas Ismay and his two sons, J. Bruce Ismay and James Ismay, were in adjoining partitioned offices on the ground floor and Mr Imrie, Ismay’s partner in the original business, was in a curtained-off alcove in the corner of one of the main offices. Margaret Ismay, who visited her husband Thomas at his office a few weeks after he moved in, did not approve even though there were coal fires in all four directors’ offices. ‘The offices look very business-like but I miss the cosiness of the old ones,’ she wrote in her diary.

By 1912, J. Bruce Ismay was in charge of the business. He had inherited his father’s petty meannesses, always taking a tram to the office and imposing his own values on others. One of his fellow directors, Colonel Henry Concanon, who liked to travel to work in the privacy of a dog cart, would get his groom to drop him off round the corner and walk the short distance down James Street so that he could be seen by Ismay to arrive at the office on foot.

When Andrew Hume arrived at the White Star Line building at 30 James Street just before midday, it looked like a temple under siege, the grandness of its architecture at variance with the humanity surrounding it. In the absence of any information from the company, distraught relatives and friends desperate for news of loved ones had decided, like Andrew, to tackle the White Star Line head on. They were ‘men and women of all classes of society’, as the

Liverpool Post & Mercury

described them in the following day’s paper. Some had been sleeping outside the building all night. Many of the women were in tears. Men were shaking their fists and demanding information. Among the crowd was the Revd Latimer Davies, vicar of St James, Toxteth, who had come to seek information about three parishioners who were crew members on the ship. A notice board on an easel had been placed on the pavement near the entrance, presumably to list names of survivors, but there was nothing written on it.