Amazing True Stories of Execution Blunders (8 page)

On 21 July 1786, the day of retribution, Charles-Henri was sent for and told that the prisoner had shown great displays of temper whilst in prison and would no doubt do so when informed of her sentence. Aware of his responsibilities and also that, rather than delegate it to an underling, he would have to administer the beating himself (the Comtesse being of noble blood), he realised that he would have to take all measures necessary to minimise any disturbance. Going to the prison, he told the gaoler’s wife to inform the Comtesse that she was wanted in the corridor by her counsel. As soon as the prisoner left the cell, the executioner’s assistants seized her arms as, on seeing them, she desperately tried to escape.

Charles-Henri was able to have a good look at his victim. He later wrote:

‘She was rather small in stature . . . her expressive mouth was large and her eyes rather small. What was remarkable was the thickness and length of her hair and the whiteness of her skin, the smallness of her hands and her feet. She wore a silk déshabillé, striped brown and white, and covered with small nosegays of roses, and her head was covered with a small cap.’

Held firmly by the assistants and also surrounded by four police officers, the Comtesse trembled slightly as Charles-Henri said, ‘We wish you to listen to your judgement, madame.’ She was led to the hall, where the clerk proclaimed the verdict of guilty; as he did so, her eyes rolled in their sockets and she bit her lip, her hitherto pretty face a mask of fury. When the clerk came to the penalties her rage exploded into uncontrollable violence, a protracted struggle ensuing between her and her escorts.

Eventually overpowered, she was then tied up and carried down to the public courtyard where the scaffold awaited. Despite it being only six o’clock in the morning, a crowd of hundreds had gathered, and as her bonds were loosened, she ran towards the edge of the scaffold, a further frantic struggle taking place as, with an effort, they managed to strip the clothing from her and force her to lie down on the bench so that Charles-Henri could administer the beating.

A vivid description of what followed was portrayed in a journal written by Nicolas Ruault:

‘Her whole body was revealed – her superb body, so exquisitely proportioned. At the flash of those white thighs and breasts, the rabble broke the stunned silence with whistles, catcalls and shouted obscenities. The prisoner slipped from his grasp, the executioner, branding iron in hand, had to follow her as she writhed and rolled across the paving stones of the courtyard. The delicate flesh sizzled under the red-hot iron. A light bluish vapour floated about her loosened hair. At that moment her entire body was seized with a convulsion so violent that the second letter ‘V’ was applied, not to her shoulder, but on her breast, her beautiful breast. Mme de la Motte’s tortured body writhed in one last convulsive moment. Somehow she found strength enough to turn and sink her teeth into the executioner’s shoulder, through the leather vest, to the flesh, bringing blood. Then she fainted.’

On recovering she was taken back by coach to the prison where, as the vehicle slowed down, she tried to throw herself under the wheels. In her cell she vainly tried once more to commit suicide by choking herself with a corner of her bed sheet. But her imprisonment lasted, not for life, as sentenced by the court, but for a brief ten months, for with the help of a sentry whom she bribed, she escaped to England disguised as a man and joined her husband in London, where she lived until her death in 1791.

In 1581, having penned seditious writings against Queen Elizabeth’s proposed wedding plans, John Stubbs was sentenced to have the offending hand amputated. Just as the executioner positioned his meat cleaver on the joint of his victim’s right wrist and raised the mallet to strike it, Stubbs, patriotic almost beyond belief, raised his hat with his other hand and, waving it in the air, shouted, ‘God save the Queen!’

William Prynne, MP

The one thing a seventeenth-century author and Member of Parliament should never have done was offend members of the royal family, yet that was exactly what William Prynne did when he wrote a book criticising the theatrical profession because one person who loved acting was the Queen (Henrietta Maria) herself. Her husband, Charles I, was so furious that Prynne not only found himself serving twelve months in prison, but was also fined £5,000. Nor was that all, for what really hurt, in more ways than one, was that his sentence included being taken to Westminster where the public executioner removed one of his ears, and from thence to Cheapside, where the other was similarly amputated. Nor was the front of his face overlooked; an additional penalty required his nose to be slit down the centre. One hopes that he could see without the need for spectacles or pince-nez.

Far from being cowed into submission, the now no longer good-looking author proceeded to publish pamphlets criticising the bishops, hardly a wise move, for once again he was brought to trial. In court a member of the bench ordered the usher to expose the prisoner’s scars. The official did so, pushing back Prynne’s flowing locks to reveal a stub of gristle protruding from one side of his head.

‘I thought that Mr Prynne had no ears at all,’ quoth one of the judges, ‘but methinks he hath ears after all!’ Determined to deprive him of what little remained of his sole surviving aural organ, the court sentenced him to lose the stub, to be branded and imprisoned for life – and to be fined another £5,000.

So one fine day in 1637 the appropriately named Gregory Brandon heated two irons, ‘S’ and ‘L’, for Schismatic Libeller (heretical libeller) and applied them, one to each of William’s cheeks. Unfortunately, in the heat of the moment he must have applied one iron upside down, and so had to burn it in again but at least was compassionate enough to ask the attendant surgeon to relieve the agony by applying a plaster. That having been done, Brandon continued to carry out the rest of the court’s sentence by cutting off the residue of Prynne’s ear; such a tricky bit of surgery that in so doing, he sliced off some of Prynne’s cheek as well.

In 1635, while on his way to Tyburn and execution, Thomas Witherington said to the sheriff ’s deputy, ‘I owe some money to the landlord of the Three Cups Inn a little further on and I’m afraid I’ll be arrested for debt as I go past his door, so could we detour down Shoe Lane and Drury Lane so we don’t get stopped at the inn, and so miss my appointment at Tyburn?’

The deputy, entering into the spirit of it, said that he couldn’t alter the cart’s route, but if they were stopped by the innkeeper, he, the deputy, would certainly go bail for Thomas. And so Witherington, ‘not thinking he had such a good friend to stand by him in time of need, rode very contentedly to Tyburn.’

Burned at the Stake

Catherine Hayes

At dawn on 2 March 1726 a watchman found a man’s head and a bloody bucket in a dock near Horseferry Road, Westminster. The head was taken to St Margaret’s graveyard and, having been washed of the blood and dirt, it was displayed on a pole for three days for purposes of identification, and then placed in a large glass container full of spirits and shown to anyone who wished to see it. Three weeks later it was recognised as being that of a well-to-do man named John Hayes who lived in Chelsea, and suspicion fell on his wife Catherine. She was arrested and expressed a desire to see the head; on doing so she kissed the container and begged to have a lock of the content’s hair.

While she was being interrogated, it was reported that the limbs and torso of a man had been found wrapped in blankets, lying in a pond in Marylebone Fields near the Farthing Pie House. Further enquiries elicited the fact that at a party in the Hayes’ house, at which two other men had been present, a quarrel had started, during which Hayes was murdered with a hatchet by one of the men, Billings, whereupon Catherine had said, ‘We must take off his head and make away with it, or it will betray us.’ And she, together with Billings and the other man, Thomas Wood, cut it off with the latter’s pocket knife, put it in a bucket and threw it into the Thames. Catherine had next suggested that the body should be put in a box, taken by coach to Marylebone, and there thrown into the pond. As it was too large for the box, she then suggested that it should be cut into pieces.

All three were confined in Newgate Prison and put on trial. Billings and Wood, found guilty of murder, were hanged, Billings’ corpse being later gibbeted. Catherine Hayes was charged with Petty, or Petit, Treason, and accordingly sentenced to be burned to death (High Treason was the crime of plotting or causing the death of the sovereign, the ‘leader’ of the nation; the penalty was to be hanged, drawn and quartered. Petty Treason was that of causing the death of the husband, the ‘leader’ of the household, and if committed by his wife she was sentenced to be burned).

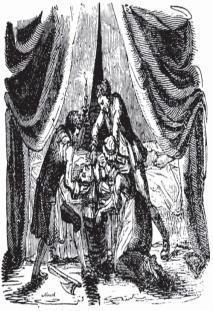

Catherine Hayes Decapitating Her Husband

Catherine Hayes was drawn on a sledge to Tyburn where she was chained to a stake, kindling and brushwood being piled around her. A rope around her neck was then passed through a hole in the stake, but it was reported that:

‘at the very moment that the fire was put to the wood that was set round, the flames reached the offender before she was quite strangled by the hangman, for, the fire taking quick hold of the dry wood, and the wind being brisk, blew the smoke and blaze so full in the faces of the executioners, who were pulling on the rope, that they were obliged to let go their hold; more faggots were then piled on the woman, and in about three or four hours she was reduced to ashes.’

Saint Laurence, a Christian martyr, was sentenced to death by the Romans in

AD

258. He was secured to a gridiron, a rectangular framework of narrow iron bars, and a fire was lighted beneath it. As the cruelly slow grilling took effect he, with defiant humour, called to the executioner, ‘This side is roastyd enough, oh tyrant great; decide whether roasted or raw thou thinkest the better meat!’

St Laurence Tortured On A Gridiron Over The Fire

Nicholas Ridley, Bishop of London

Man Burned At The Stake

Lady Jane Grey was proclaimed Queen in 1553, and Nicholas Ridley promptly denounced Princesses Mary and Elizabeth. When Jane was overthrown by Princess Mary, who then became Queen, he was committed to the Tower, deprived of his bishopric, declared a heretic and sentenced to be burned at the stake.

On 16 October 1555 he was taken to Oxford to suffer death by fire. A friend brought a bag of gunpowder and hung it round Ridley’s neck. ‘I will take it sent of God,’ the Bishop said, although in that position the fire would have had to be well alight before it reached the explosive.

Unfortunately the branches had been stacked too thickly over the kindling and so the latter could not burst into flame; instead it continued to smoulder, white-hot, around his legs, prolonging his agony. ‘I cannot burn!’ he exclaimed. ‘Lord have mercy on me, let the fire come to me, I cannot burn!’