Amazing True Stories of Execution Blunders (10 page)

The first relay of current, lasting for fifty seconds, entered the jars and surged through his body via his arms, but when it was switched off it was very evident that either the method, the amount of voltage or the duration was incorrect, for from McElvaine came a moan, saliva pouring from his mouth. At this, the official in charge urgently exclaimed, ‘Switch the current to the head and leg electrodes!’

As this was done, the condemned man stiffened in the chair, the now anticipated smell of acrid flesh and burnt hair filling the small chamber. Thirty-five seconds, seeming like minutes, passed before the current was eventually switched off and the doctor announced that the victim was dead – but the saltwater-filled jar method had proved disastrously ineffective, and was never used again.

Killer Michael Sclafoni was sentenced to death in 1930. Undaunted at the sight of the electric chair, he ran his fingers over one of the arms and shook his head. ‘Dust!’ he exclaimed and asked for a cloth. Given one, he proceeded to wipe the arms and the chair seat meticulously, then handed it back, commenting scornfully, ‘They could at least have given a man about to die a clean chair!’

Ethel Rosenberg

The law does not differentiate between male and female victims, nor does high voltage, so when Ethel Rosenberg and her husband Julius were found guilty of being Communist spies, both perished in the electric chair on 19 June 1953.

Following her husband’s execution – which apparently was accomplished without mishap – Ethel, wearing a green dress with polka dots, was escorted into Sing Sing’s death chamber by two of her guards and seated in the chair. Seemingly calm and composed, she didn’t flinch as the helmet fitted with the cathode element was placed over her head, its visor concealing her face from the observers present, and the other electrode was attached to the calf of her leg.

Executioner Joseph Francel delivered the first shock, followed by a further three. The sequel was reported in the

Sunday Dispatch

of 21 June:

‘After the fourth shock, guards removed one of the two straps and the two doctors applied their stethoscopes. But they were not satisfied that she was dead. The executioner came from his switchboard in a small room ten feet from the chair. ‘Want another?’ he asked. The doctors nodded. Guards replaced the straps and for the fifth time electricity was applied.’

There was no mention of any signs of life after the first surge of electricity, and one would like to hope that that at least rendered her unconscious.

While Thomas Tobin was serving a prison sentence in Sing Sing Prison for robbery, it was decided to build a block of single cells, and Tobin, his other profession being that of a skilled mason, agreed to assist in the construction. He contrived to incorporate a short tunnel leading to a sewer which drained into the Hudson River, and he later used it to escape. He was eventually recaptured and completed his original sentence, but on his release in 1904 he committed further felonies, resulting in the death sentence. Back in Sing Sing he found himself in a cell which he instantly recognised. ‘To think,’ he exclaimed bitterly, ‘that I should’ve built this place myself! I built my own tomb, that’s what I did!’

William G. Taylor

A veritable series of errors combined to create total catastrophe when Taylor, sentenced to die for murdering a fellow inmate, was secured in the electric chair and the process began. As the first surge of current hit him his whole body straightened so violently that although the leg straps didn’t break, the front of the chair itself did, coming apart from the rest of the structure. The power was switched off immediately, a guard procured a box and propped up the chair, and the doctor, assuming that the shock had proved fatal, routinely checked the victim’s heartbeat – discovering, much to his surprise, that the man was still alive.At that, the warden gave the signal to the executioner to apply another surge of current. In his adjoining room, the official did so only to find that nothing happened, and on hastening to the powerhouse he discovered that the generator, overloaded by the amount of current it had to supply, had burnt out. Moreover there was no back-up or reserve equipment!

Faced with a totally unexpected situation, the warden had no alternative but to order that Taylor, now unconscious as a result of the first shock, be released from the chair and placed on the hospital trolley which had been brought into the death chamber. Drugs were then administered to him to ensure that he didn’t regain consciousness.

Meanwhile the prison electricians were frantically connecting long lengths of cable extending from their electricity sub-station to reach beyond the prison walls in order to obtain further electricity from the city’s supply. Although they were not to know it, their haste wasn’t necessary, for Taylor had already died on the trolley. When, an hour later, electricity supplies to the prison had been restored, Taylor’s corpse was carried back to the chair, strapped in and subjected to a further thirty seconds of high voltage. For the law, of course, had to run its course in full.

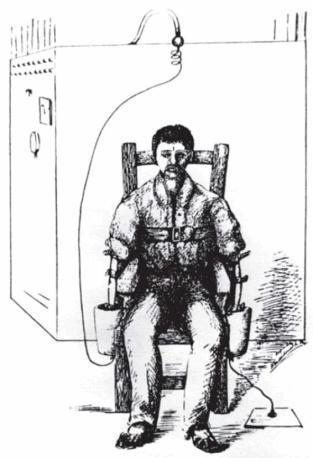

Early Electric Chair

The saying ‘the condemned man ate a hearty supper’ must have originated with one American prisoner in the 1930s, who ordered a Long Island duck, a can of peas and one pint of olives, all mixed into a brown stew with dumplings and boiled rice, together with tomato salad and four slices of bread. Then after finishing his sweet, which consisted of strawberry shortcake and a pint of vanilla ice-cream, he relaxed and smoked a few cigars. Following this feast he exclaimed, ‘Right – I’m ready now to ride that thunderbolt, boys!’

Fred Van Warmer

Sentenced to death for the murder of his uncle on Christmas Eve 1901, it was two years before all appeals failed and Fred Van Warmer finally occupied the electric chair. The executioner, Robert Elliott, had sent two shocks of 1,700 volts coursing through the man’s body for no less than two minutes, and was subsequently instructed to switch the power off. Having been pronounced dead by the doctor, Van Warmer’s body was then released from the chair and carried into an adjoining room to await the routine autopsy. However, a passing guard happened to walk through the room and to his horror saw the ‘corpse’ move one of its hands, and one eyelid flicker. Shocked, he ran out to locate the doctor, calling as he did so, ‘He moved! I saw him move! We’ve got to do something quickly!’

The warden and the other guards hastily reassembled and replaced the victim in the chair, where a further shock was administered; one so intense that when switched off, no doubt at all remained that Van Warmer had finally succumbed.

A later post-mortem revealed that Van Warmer’s heart was larger than that of any previous occupant of the chair, a possibility that had to be taken into account when planning future executions

A disabled felon sentenced to the electric chair had made a will in which he bequeathed his wooden leg to a newspaper reporter who had written some disparaging articles about him, adding in a codicil that he hoped the newsman would need it sometime

!

Frank White

Frank White was a farm worker who had brutally murdered his employer and then hidden the body in a bale of hay. A violent prisoner while in jail, he refused all spiritual solace and was expected to resist as much as possible on being taken into the death chamber. However, the reverse was very much the case, for when escorted in, he was on the point of utter collapse and had to be supported by two guards. On seeing the chair he struggled wildly, shouting, ‘Don’t kill me! Don’t do it! Don’t do it!’

Somehow the guards got him into the chair and overpowered him long enough to strap him down. Further force had to be used to keep his leg still while the electrode was attached to his calf and, the other contact having been positioned on his head, the executioner operated the switch. Shock after shock of high voltage was applied, and after the fourth one, Dr Ulysses B. Stein, the physician on duty, checked with his stethoscope and announced, incredulously, that the man’s heart was still beating.

The doctor then shakily resumed his seat in the front row of the gallery, but as the fifth shock was about to be administered, he fainted, collapsing onto the floor, and had to be carried to another room, where he soon recovered. During the subsequent two final shocks, many of the other onlookers were also understandably horrified by the gasps and gurgling noises coming from the victim, these sounds apparently being caused by the air escaping from his lungs.

During the uprising in the Vendée region of France, the revolutionary mayor wrote to his opposite number in Paris on 1 January 1794, saying, ‘Our Holy Mother Guillotine works. Within three days she has shaven eleven monks, one former nun, a general, and a superb Englishman, six feet high, whose head was de trop. It is in the sack today.’

Firing Squad

Samuel and Malcolm McPherson and Farquar Shaw

This, a tragic episode in the history of the British Army, occurred in 1743 when 800 Scotsmen of Lord Sempill’s Regiment (which later became the Black Watch) were inveigled south under the pretext of being reviewed by George II, only to suspect that they were actually to be sent to the then plague-ridden colonies of the West Indies and Africa. Encamped on Finchley Common, London, 110 of the men mutinied and set off to march in an orderly fashion back to Scotland. When the alarm was raised the Government sent three companies of dragoons (mounted soldiers) after them and offered a bounty of forty shillings to anyone who could capture a deserter. The pursuing soldiers caught up with the Scotsmen in Northamptonshire and escorted them back to London where they were imprisoned in the Tower. Court martials of three leaders followed, the two corporals, cousins Samuel and Malcolm McPherson, and Farquar Shaw, the piper (without such a musician, of course, no Scotsman would march anywhere!). In order to set an example, all three were sentenced ‘to face death by musketry’ (before a firing squad).

At 6 a.m. on 18 July 1743, the three condemned men knelt on planks positioned in front of a blank wall of the Royal Chapel of St Peter ad Vincula within the Tower. All their fellow deserters were drawn up in a wide arc in front of them, forced to watch the fate of their comrades, and encircling them to prevent any escapes, were 300 men of the regiment on duty in the Tower at the time, the 3

rd

Regiment of Foot which, ironically, later became the Scots Guards.

The three victims, wearing their shrouds under their uniforms, were ordered to pull their hats down over their faces; meanwhile the firing squad of eighteen men, six of whom were held in reserve, had been drawn up behind the Chapel. When the time came, as reported by General Williamson, Deputy Lieutenant of the Tower,

‘they now advanced round the corner of the Chapple and with the least noise possible, their Muskets already being cocked for fear of the Click disturbing the Prisoners, Sergeant Major Ellison – who deserves a greatest commendation for taking thisPrecaution – waved a handkerchief as a signal to ‘Present’, and after a very short Pause, as they aimed four to a man, waved it a second time as a Signal to ‘Fire’.’

All three men fell instantly backwards, apparently dead, but despite the squad having fired at more or less point-blank range, it demands a lot for soldiers to have to aim deliberately at fellow soldiers and pull the trigger, so it was hardly surprising that some bullets missed their targets. Shaw was seen to move his hand, so one of the six reserve members of the firing squad was ordered to advance and deliver the

coup de grâce

by shooting him through the head and Samuel McPherson had to be shot again through the ear.

The bodies were stripped to their shrouds and buried in an unmarked grave before the door of the Chapel, only yards from where Anne Boleyn and the other executed queens lie interred beneath the altar. The surviving deserters were duly dispatched to the colonies, few, if any, ever to return.

Admiral John Byng was court-martialled in 1757, charged with showing cowardice in the face of the enemy in that he failed to engage a French squadron near Minorca. His defence, that the French admiral had superior armament, was rejected and he was sentenced to death by firing squad. He was later visited by a friend who casually stood next to him and then wondered aloud as to whom did he think was the taller. ‘Why this ceremony?’ asked Byng. ‘I know what it means – let the man himself come and measure me for my coffin.’

When he faced the firing squad he requested that he should not be blindfolded, but was then told that it would only unnerve the soldiers and would distract their aim to see him looking at them. ‘Oh, let it be done, then,’ he conceded. ‘If it wouldn’t frighten them, it wouldn’t frighten me.’