Alphabetical (32 page)

Authors: Michael Rosen

The âquick', âquiet' and âquite' words give people a bit of alliterative play: we like the sound of being âquite quiet' and âquite quick' and ducks go âquack-quack'.

T

HOUGH

I

MEET

up with the alphabet every day, it doesn't come in alphabetical order. It is presented to me as

QWERTYUIOP

. Prior to the invention of the qwerty keyboard on the early typewriters, the word âalphabet' meant two things at the same time: the letters that we use and alphabetical order or âthe ABC'. Both physically and mentally, the alphabet was stored alphabetically. The peoples who used the alphabet didn't really have another way of conceptualizing it.

Now, though, I sit down and select letters from a store that is arranged completely differently. One peculiarity of this is that I can recite the alphabet in a few seconds, I can touch-type, but I can't recite qwerty. So I know these two methods of storing the letters in different ways. If you arranged a dictionary or register of people at a conference in qwerty order, most of us would be lost. Yet I can't help feeling that qwerty, in its own way, subverts the orthodoxy of the alphabet. Day after day, for millions of people worldwide, it demands that we go to it and to its own special way of ordering literacy. The ABC alphabet has bitten back, though: the keyboards on our phones are in

alphabetical order. As a qwerty-trained typist, I find it confusing to collect my pre-paid tickets from a machine on a railway station if the on-screen keyboard, looking exactly like a qwerty one, is arranged in alphabetical order. I can't find the letters to punch in my code!

Qwerty people have a hidden side: we have had relationships with different machines all through our lives, sometimes loving, sometimes resentful, sometimes dominant, sometimes being dominated. Part of our biography is in the play of our fingers over keys.

The story of the qwerty keyboard is intimately connected to a man called Charles Latham Sholes, who was one of the forces behind the abolition of capital punishment in Wisconsin. In 1851, John McCaffary, an Irish immigrant, had been sentenced to death and before a crowd of some 2,000â3,000 people he was hanged from a tree. McCaffary remained alive for some twenty minutes before eventually dying. This spectacle gave added strength to the campaign to abolish the death penalty, led by Sholes, first as a newspaper man for the

Kenosha Telegraph

and then as a senator in the Wisconsin Assembly. When the abolition bill was passed on 12 July 1853, John McCaffary became both the first and the last person to be executed in the state of Wisconsin.

It was Sholes and his friends who first created a typing machine that could be exploited commercially and it was Sholes in conjunction with a business associate, James Densmore, who first came up with the qwerty keyboard in 1873. By then, the patent was in the hands of Remington and the world's first qwerty typewriter â or QWERTY typewriter (it was upper case only) â appeared on 1 July 1874. It was the âRemington No. 1', also known to aficionados as the âSholes and Glidden' after its designers.

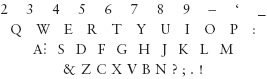

Clearly, âqwertyuiop' on a top row, âasdfghjkl' on a second, and âzxcvbnm' on a third, is a long way from âABCDEFGHIJ', âKLMNOPQRS' and âTUVWXYZ'. This layout came about because the model of typewriter Sholes, Soule and Densmore were playing with, using âABC', caused the âtypebars' (the thin metal arms on the end of which were the letters) to collide and jam. Densmore figured that the problem lay in letter frequency, the number of times a letter was used in English writing. He asked his son-in-law, a school superintendent in Pennsylvania, to tell him which letters and letter combinations appear most frequently. The trick to avoid the clashing was to place the most commonly occurring letters (on the end of their respective typebars) as far apart as possible. The easiest way to make this happen mechanically, was to arrange the keyboard like this:

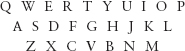

Remington adjusted this, so that by 1878 it was:

Mistakenly, some people have said the qwerty layout enabled people to type faster. In fact, it was designed to slow typists down, requiring them to use different fingers or different hands for letters which were likely to appear together. What's odd is that it's survived. An electronic keyboard won't jam. There are

no âtypebars'. Given that most people's quickest fingers are likely to be the index finger of each hand, one way to make typing faster would be to situate high-frequency letters within the orbit of those two fingers and the least frequent in the orbit of the third and fourth fingers.

If you can touch-type, you can expose yourself to a disconcerting experience by trying to touch-type on a keyboard with a slightly different arrangement. In France they use the âazerty' keyboard which is arranged like this:

as opposed to (to remind you):

No one knows exactly why France adopted âazerty' and any efforts to alter it have failed.

As Sholes sold the patent to Remington he made very little money out of his contribution to typewriting and keyboards. He is recorded as saying: âWhatever I may have felt in the early days of the value of the typewriter, it is obviously a blessing to mankind, and especially to womankind. I am glad I had something to do with it. I built it wiser than I knew, and the world has the benefit of it.' Densmore was more canny. He retained a royalty and died with half a million dollars to his name.

As with most technology, the typewriter and the keyboard can be seen as both emancipating and oppressing at the same

time. It enabled millions of women to earn money independently, and to see worlds other than their homes. On the other hand, it put those same women into what used to be called âthe typing pool', where, all day and every day, they pounded typewriters to âwrite' what wasn't their own writing on the machines that weren't theirs. I can now see the importance of my mother owning her own typewriter. It enabled her, in the 1940s and 50s, to write what she wanted to write and present it with the same quality as the best around.

The first typewriter I saw belonged to my mother. My mother was Mum, to my father she was âCon', to friends she was âConnie', to children and colleagues at her school she was âMrs Rosen', but in a disconcerting way, every so often she was a âtypist' and a âsecretary'. She became this because of a locked black box stored in our âfront room' along with a furry square mat. This was her Remington typewriter, which she could sit at for hours, threateningly ignoring the rest of us, typing away without looking at the keys, at a rate of clacketty-clacks matched only by the speed she clacketty-clacked with her knitting. We could see that there was an inaccessible, unreachable part of Mum working away in there that wasn't very Mum at all. It belonged to some earlier pre-Mum era when we didn't even exist.

I liked to sit next to her and watch how her long fingers hammered away, how the metal letters stuck on their thin arms flailed to and fro, how the ribbon jumped up and down, and the ribbon's wheels jigged round. I liked the way things got stuck every so often and she would hesitate for a moment, poke her finger into the jangled arms, release them and carry on.

And the page of type: how could it be so perfect, its titles underlined, the margins so neat, the lines of type spaced so

evenly? She explained how the âreturn' could be altered, how you could arrange it so that the margins were regular. She showed us how to change the ribbon and â best of all â she let us clean the metal letters with a toothbrush. The tiny metal flanges of the letters would get a build-up of ribbon fibre and ink, and the toothbrush would get them sharp and shiny again. I loved the keys themselves: each letter was printed on to the cream-coloured disc of the key, looking as if it was under glass, surrounded by its own circular ridge of metal. Then the noise would stop. She would put the machine back in its box and slot it back in the alcove.

We weren't allowed to use it on our own. This was a special and expensive machine. For letters to appear on a page as cleanly and beautifully as this, she couldn't risk my brother and me just playing about on it. It was too important. This way of producing letters on the page had its own black box. This kind of alphabet was under lock and key. This kind of alphabet was handled by someone extremely clever who had gone to a special college to learn how to do speed clacketty-clacking.

The mystique was dented when my parents found us an old typewriter. It had no case. There were one or two letters that didn't type. The right-hand margin clip was broken. So? It was a typewriter and my brother and I spent hours on it. First as one-finger typers and then as two-finger typers, then as two-finger-and-a-thumb-for-the-space-bar typers. Because it didn't have a case, it grew fluff. Fluff got in amongst the thin arms that held the letters and under the keys. Norman and Butt, the estate agents in the shop beneath our flat, threw their old typewriter ribbons into the dustbins in our yard. My brother and I went through the bins and found two-coloured ribbons â half black, half red â and we put these on our typewriter so that we could write in two colours. Our forefingers were learning qwerty. We

could make pages of print â of a kind â just like a professional, just like Mum. Or nearly. We knew that it wasn't as good as hers. But hers had to be better than good.

Once she wrote and typed a story about a girl she taught and sent it off to the BBC. The BBC said they liked it and she was on the Home Service reading it. I asked the head teacher if I could go to the Physics lab to listen to it. He said, âNo.' I was disappointed. He said, âNo, you can listen to it with me in my study and I'll get someone else to do assembly that morning.' So I sat with the headmaster, on a chair old enough for Shakespeare to have sat on, he said, and we listened to my mum reading the story that she had typed on her typewriter. âVery good,' he said. âShe was very good.'