A History of Britain, Volume 3 (38 page)

Read A History of Britain, Volume 3 Online

Authors: Simon Schama

Emily’s distress at the spectacle of famine was genuinely heartfelt, but relative. When her pet flying squirrel died after eating a cholera-infected pear in August 1839 Emily became really upset. But then, as she confessed, ‘my own belief is that as

people

in India are uncommonly dull, the surplus share of sense is “served out” to the beasts, who are therefore uncommonly clever.’ The Westernizers of the 1840s had a mixed reaction to the shocking spectacle of mass starvation in India. The gung-ho improvers like James Thomason in the Punjab, or the new Governor-General Lord Dalhousie, who succeeded Auckland in 1842 after the catastrophic Afghan war in which just one army surgeon from a force of 4000 survived a winter retreat over the Hindu Kush, were strengthened in their belief that the gifts of the West, like new roads, railways and irrigation canals, were the long-term answer. A great Ganges canal was built, expressly to avoid a repetition of the famine of 1837–8. But there were other voices for whom famines were the inevitable, if regrettable, pangs of a difficult transition to the modern world economy. In a country of too many mouths to feed, with plots of land that were too small to be viable producers for the cash market, there were bound to be some casualties of the process of rationalization. In due course their labour would be absorbed by a booming urban sector, just as had happened in industrial Britain. But nothing of this magnitude happened without suffering. What was more, the obstacles to modernization were as much social and cultural as structural. Peasants were accustomed to an easy-going, unambitious seasonal round in which long periods of sloth were punctuated by frantic activity. If they were to be profitable producers they had to be made self-reliant, persevering and, above all, regular in their labour. A cursory glance at an ant-hill would give them the idea.

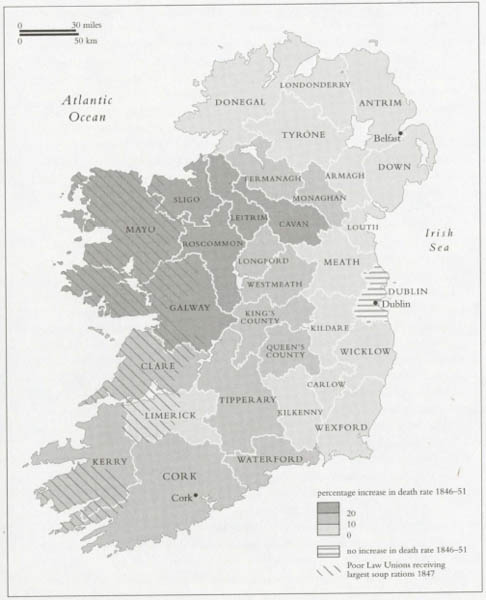

This, at any rate, was what Charles Trevelyan believed, not just about India but also about Ireland, where the most horrifying of all modern western European famines occurred between 1846 and 1850. During those years Ireland lost a quarter of its population: 1 million died of starvation or famine-related diseases, and another million turned to emigration as their only chance of survival. In the worst-hit regions of the west, like County Mayo, nearly 30 per cent of the population perished. It

was

Charles Trevelyan at the treasury who had been responsible for direction of relief operations, but who believed, without malice yet without sentimentality, that the ordeal had been inflicted by Providence to bring Ireland through pain to a better way of life. His bleak conclusion was that it had all been ‘the judgement of God on an indolent and unself-reliant people, and as God had sent the calamity to teach the Irish a lesson, that calamity must not be too much mitigated: the selfish and indolent must learn their lesson so that a new and improved state of affairs must arise’.

The Times

was even more brutal in its insistence that the famine had been a blessing in disguise. Where no human hand or wit had been capable of getting Ireland out of cycles of poverty and dependence, all knowing Providence had supplied a ‘check of nature’. ‘Society’, the newspaper announced like a Greek oracle, ‘is reconstructed in disaster.’

Although, on the face of it, the cases of India and Ireland seem separated by more than oceans, there is no doubt that they were closely connected in much of the most serious Victorian thinking and writing about the intractable problems of over-population and under-production. Thomas Malthus, of course, had taught at Haileybury, the East India Company college, and Charles Trevelyan had been his star pupil, steeled for life by Malthusian doctrine against the spectacle of famine in either India or Ireland. One of Malthus’s disciples, William Thomas Thornton, published his

Over-Population and its Remedies

in 1846, exactly at the moment when the enormity of the Irish disaster was becoming plain, and his proposals for thinning the density of cultivators, partly by voluntary birth control, partly by emigration, had a direct impact on contemporary debates. Anti- or non-Malthusian liberals who directed their fire at British governments for tolerating the practices of absentee landlords, determined to extract the last penny in rent from the maximum number of peasant plots, also made a habit of talking about India and Ireland in the same breath. The philosopher John Stuart Mill, in one of the series of articles he wrote on the Irish land problem between 1846 and 1848, insisted that ‘those Englishmen who know something of India are even now those who understand Ireland best’. George Campbell, a district commissioner for provinces in central India, wrote the book on Ireland that, more than any other single source, moved William Gladstone to grasp the nettle of land reform in the 1870s. Reports of poverty and insecurity in County Mayo or County Cork, Campbell wrote, ‘might be taken, word for word, as the report of an administrator of an Indian province’.

The difference, Mill thought (with the benefit of his own relative ignorance about the subcontinent), was that those who decreed benevolent reform for India did not have to worry about politics, nor were they

inheriting

iniquities from the conquests and land settlements of centuries before. A benign, educated administrator, he thought, could decree ‘Improvement’ for the cultivators of Bihar or Gujarat and it would happen. Indeed, under Dalhousie, Mill thought it was indeed happening, in the shape of the Ganges canal.

It was certainly true that those charged with managing the nightmare of the Irish potato famine – from the two prime ministers, Sir Robert Peel and Lord John Russell, to their presidents of the board of trade and chancellors of the exchequer, and treasury officials like Trevelyan – all had to think hard about the political implications of any move they made. But it was also true that most of the politicians and civil servants were in the grip of a set of moral convictions that allowed them to think that whatever they did would always somehow be over-ridden by the inscrutable will of the great Political Economist in the sky. God willed it, apparently, that, as

The Times

put it, the ‘Celts’ stop being ‘potatophagi’. God willed it that the feckless absentee landlords take responsibility for the evil system they had perpetuated. God willed it that there should be a great exodus and that vast tracts of western Ireland should become depopulated. Or was it heresy to think that these things had been made, or made worse, by the hand of man? One of those heretics was the Tory prime minister Sir Robert Peel, who had to deal with the first phase of the calamity. In February 1846, in a speech to the Commons, trying to persuade them to abandon the Corn Laws that prevented the free import of, among other grains, American corn, Peel concluded by advising the members:

When you are again exhorting a suffering people to fortitude under their privations, when you are telling them, ‘these are the chastenings of an all-wise and merciful Providence, sent for some inscrutable but just and beneficient purpose …’, when you are thus addressing your suffering fellow-subjects … may God grant that by your decision of this night, you have laid in store for yourselves the consolation of reflecting that such calamities are,

in truth

[my emphasis], the dispensations of Providence – that they have not been caused, they have not been aggravated by laws of man, restricting in the hour of scarcity the supply of food!

What, then, if anything, could have been done to make the misery less brutal? Could, for example, the scale of the disaster have been predicted? During the second half of the 19th century a whole school of writers published what they took to be famine predictors for another part of the

empire

that suffered famines – India: a combination of meteorological cycles (still imperfectly understood); price indices as early warnings of shortages; and assessments of depleted grain reserves. And with a great deal of experience behind them, they still got it wrong. So even though there had been failed potato crops in the 1820s and 1830s, nothing in those earlier crises could possibly have prepared governments, central or local, for what was about to happen in 1845. The fungus

Phytophthoera infestans

had attacked American crops, which gave it its grim nickname of ‘the American potato cholera’. The disease that appeared first on the underside of the leaves and ended by turning the potatoes to blackish-purplish slimy mush had indeed never been seen in Europe before. Even when it arrived (in Belgium and the Netherlands, as well as Ireland) it was thought – not least by many of the botanical experts called on to pronounce on the blight – to be the symptom, rather than the cause, of the rotted crop; the result of a spell of unusually cold, heavy rain. With only a quarter of the 1845 crop lost, officials in Dublin, anxious not to be alarmist, were calling the shortfall ‘a deficiency’. The optimistic assumption was that, with better weather (and there was a long, warm, dry period in the summer of 1846), there would be a return to relatively normal harvests. Misunderstanding of how the blight was transmitted was then compounded by poor advice. In the face of anxiety that there should be enough seed potatoes for the following year, peasant farmers were told (or at least not discouraged from doing so) merely to cut away rotten sections of the tubers and store what was left for planting the following spring. The microscopic spores over-wintered, and when the infected tubers were planted a second season of ruin was guaranteed.

The problem, of course, was that even in good years a very high proportion of the Irish population was living on a razor’s edge between survival and starvation. That population had trebled between the middle of the 18th century and 1845, rising from 2.6 million to 8.5 million. Two-thirds lived off the land, the vast majority on holdings too small to count as even modest ‘farms’. Ireland had traditionally been a grazing economy and the better-off regions in the north and east still produced and exported dairy goods to Britain. But rising demand from industrializing Britain had turned Ireland into an exporter of grain, especially oats and barley. Farmers who had the capital and the unencumbered land rose to the opportunity. But in the centre and west of the country, where the population rise had been steepest, landlords (often absentee) exploited the imbalance between population and available land to raise rents and lower wages. By the 1840s, the process of shrinking income and plot size had created a huge semi-pauperized population. There were 135,000 plots of less than an acre; 770,000 of less than 10 acres. The only sure thing was that the crop that promised the best yield from the wet, heavy ground, was potatoes: 10–12 pounds of them were being eaten every day by each Irish man and woman. But that was the beginning and the end of their diet, which if they were lucky was augmented by a little milk for protein, or by fish or kelp if they lived close to the shore.

The Great Famine in Ireland, 1845–9.

There were some in Peel’s government who, even at the end of 1845, thought they were seeing something like a plague of Egypt at hand. Sir James Graham, the first lord of the admiralty, wrote to the prime minister in October, ‘It is awful to observe how the Almighty humbles the pride of nations … the canker worm and the locust are his armies; he gives the word: a single crop is blighted; and we see a nation prostrate, stretching out its hands for bread.’ By December the price of potatoes and other foodstuffs had doubled and Peel, who had been returned to office in 1841 committed to retain the Corn Laws (but who had had a change of heart), now felt that he could not wait to use the Irish crisis to persuade parliament – and especially his own party – to repeal them. Secretly he bought £100,000 worth of American corn and had it ground and distributed at cost to special depots, run by local committees throughout Ireland. His hope was to use the reserve at best to stabilize prices, at worst for immediate relief. As a social by-product, perhaps the experience of cornmeal mush (initially greeted with horrified suspicion by much of the population as ‘Peel’s brimstone’) would also wean the Irish from their addiction to potatoes.

By August 1846, with a second blighted crop, it was glaringly obvious that Ireland was already in the grip of a famine. The Reverend Theobald Mathew, who wrote to Trevelyan imploring more direct free aid, saw the misery with his own eyes: ‘On the 27th of last month I passed from Cork to Dublin and this doomed plant bloomed in all the luxuriance of an abundant harvest. Returning on the 3rd instant I beheld with sorrow one wide waste of putrefying vegetation. In many places the wretched people were seated on the fences of their decaying gardens wringing their hands and wailing bitterly [at] the destruction which had left them foodless.’

Against the wishes of his party, but with strong Whig support, Peel had succeeded in pushing through the repeal of the Corn Laws in June 1846, resigning a few days later. Yet the new Whig government, led by Lord John Russell, looked at the multiplying misery dry-eyed. For some years Russell had, in fact, been one of the most severe critics of the ruthlessly exploitative habits of Irish landlords. But that was precisely why he was loath to use state aid from London to bail them out of responsibility for

the

consequences of their selfishness and greed. If the Almighty was laying a scourge across their back (for the assumption was that Irish property owners would not let their own people starve), who was he to stay His hand? This was the way in which not only Russell but also Sir Charles Wood, his chancellor of the exchequer, thought and spoke. And it was music to the ears of Charles Trevelyan, who all along had suspected Peel of being soft; and had objected, whenever and however he could, to any interference with the ‘natural’ and commercial operation of the grain market. It was not for the government, Trevelyan believed, to step in and buy up corn. If the price were right – and surely it was – private business would naturally send it to the markets where it was most needed. Manipulating those markets out of a misplaced sense of benevolence was a presumptuous meddling with God’s natural economic order. Stopping the

export

of oats, for example, was unthinkable. When the head of the relief commission, Randolph Routh, wrote to Trevelyan, ‘I know there is a great and serious objection to any interference with these exports, yet it is a most serious evil’, Trevelyan replied, ‘We beg of you not to countenance in any way the idea of prohibiting the exportation. The discouragement and feeling of insecurity to the trade from such a proceeding would prevent its doing even any immediate good. … indirect permanent advantages will accrue to Ireland from the scarcity … the greatest improvement of all which could take place in Ireland would be to teach the people to depend on themselves for developing the resources of their country.’