The Wild Queen

Authors: Carolyn Meyer

Â

Â

I. At the Center of Disastrous Events

II. As Though We Had Known Each Other All Our Lives

III. A French Girl, Through and Through

IV. A Deep Stirring I Had Never Experienced

V. It Would Not Be a Simple Matter

VI. I Could Not Afford a Foolish Mistake

VII. All That Could Have Been and All That Was Lost

VIII. A Woman Who Fights Is As Likely to Lose As She Is to Win

Copyright © 2012 by Carolyn Meyer

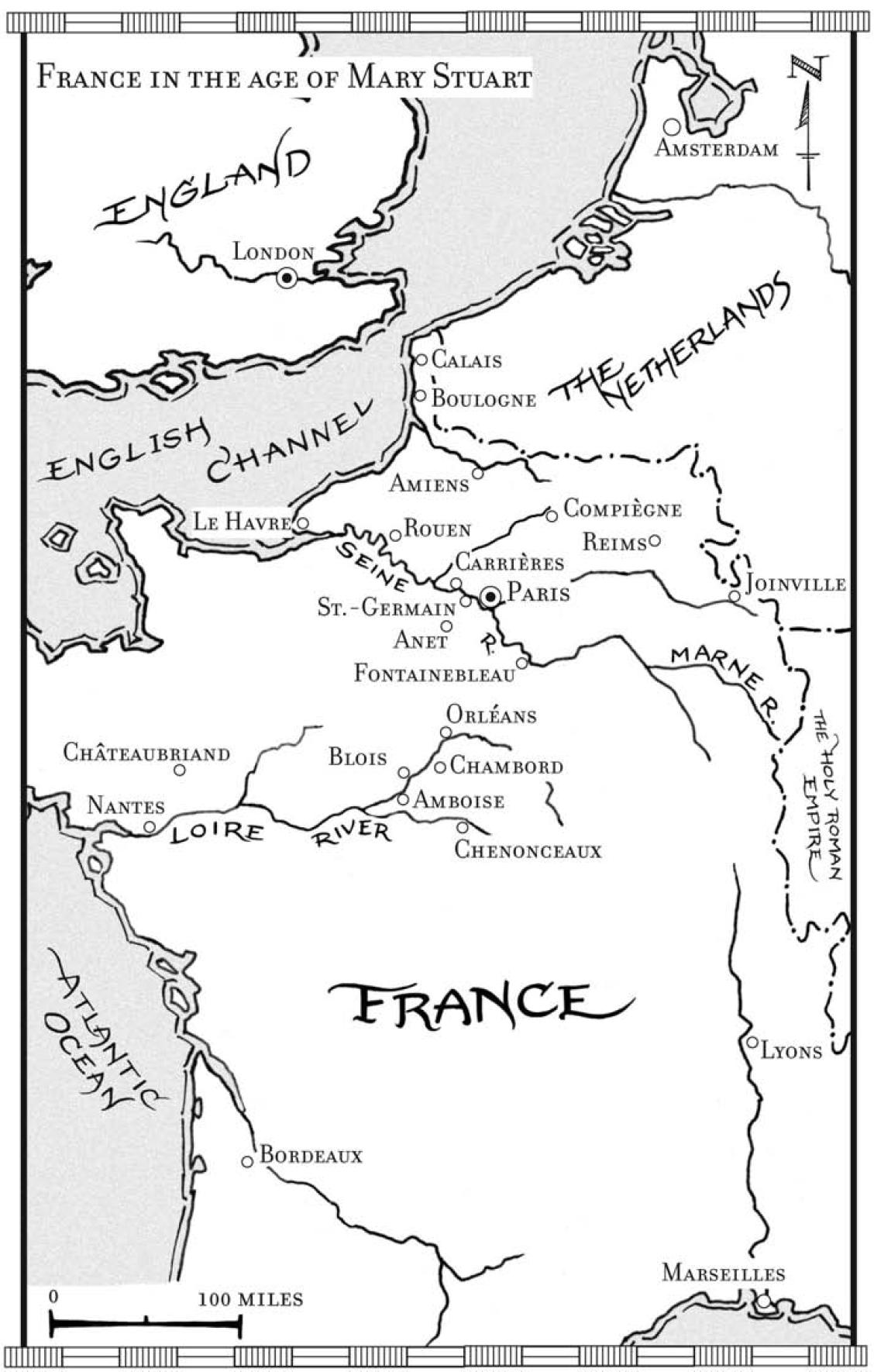

Map art © 2012 by Jeffery Mathison

All rights reserved. For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

Harcourt is an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

Text set in Requiem.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Meyer, Carolyn, 1935â

The wild queen / by Carolyn Meyer.

p. cm.

Summary: Convicted of plotting against her cousin Queen Elizabeth I of England and awaiting execution in 1587, Mary Stuart, queen of Scotland, recounts her life story including becoming a widow at age eighteen and her brutal campaign to regain her sovereignty after being stripped of her throne.

ISBN 978-0-15-206188-3

1. Mary Queen of Scots, 1542â1587âJuvenile fiction. [1. Mary Queen of Scots,

1542â1587âFiction. 2. Kings, queens, rulers, etc.âFiction. 3. ScotlandâHistoryâ

Mary Stuart, 1542â1567âFiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.M5685Whs 2012

[Fic]âdc23

2011027318

Manufactured in the United States of America

DOC 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

4500356198

For Susan Wien Groene

T

HE MIDNIGHT HOUR

being well past, the day is now Wednesday, the eighth of February, 1587. The sound of hammering in the great hall of Fotheringhay Castle has not ceased. In a few hours the most important day of my life will dawn. I have written letters to those I love. My red petticoats and my black gown lie ready. My women, dressed in black, sit with me, and I ask one of them to read aloud the story of the good thief crucified beside our Lord.

When she has finished, the women are weeping. “It is true that the thief was a great sinner,” I remind them, “but not so great as I have been.”

I lie down and close my eyes, though I have no wish to sleep. Outside the door of my dreary chambers, the guards tramp back and forth, back and forth, stationed there lest I try to escape. They need not worry My body remains here, but my thoughts have already flown away, back to my earliest beginnings and all that has followed.

Farewell, Scotland

I

WAS THE CAUSE OF MY FATHER'S DEATH

.

My father, King James V of Scotland, drew his last downhearted breath and died when I was just six days old. “He had not been ill,” my mother explained to me years later, “but was deeply saddened by his defeat at the hands of the terrible English.”

Henry VIII, king of “the terrible English,” was determined to take over Scotland. In the bloody battles between the two countries that shared a border, the outnumbered Scots always got the worst of it. After my father's humiliating loss at his last battle, he took to his bed.

My father had badly wanted a son who could be the next king. When he married my mother, a French duchess, he already had three illegitimate sons, but by law a bastard could not inherit the Scottish throne. My mother bore him two more sons; both infants died. I was my father's last hope, and when the news reached him of the birth of a lassâa girlâthat bitter disappointment was more than he could endure. Had I been a boy, he would still be alive. I have no doubt of that.

From my earliest days I have too often found myself at the center of disastrous events. That was the first. My birth killed my father, and I became queen of Scotland.

***

I was playing with my friends when the guard rushed in from the watchtower and announced to the queen, “My lady, the ships flying the colors of France are moving up the firth,” and my mother burst into tears.

“Mither?” I jumped up from my game and ran to her. I touched her cheek. “Maman?” I asked, changing to French, my mother's language.

She dabbed at her eyes and tried to smile. “Shall we go see the ships, Marie?” Her voice trembled. She took my hand, calling to my friends, “Come, dear little Maries!” All four of my friends were named Mary, as I was, but my mother called us by the French version of the nameâeven Mary Fleming, who was pure Scots. To everyone, they were the Four Maries. Trailed by governesses who always seemed to move too slowly, we dashed eagerly out of the castle and peered down over the stone parapet to see for ourselves these foreign ships far below us. A strong north wind, chilly even in July, whipped our skirts and petticoats and blew our long hair into our faces.

“Look,” my mother said, “the king of France has sent his own royal galley for you. This shows how much he honors you.”

“Me?

" I gazed up at my mother, puzzled. It was the summer of 1548, a few months before my sixth birthday, and there was much I did not yet understand.

Maman sighed deeply and pulled me close. “The time has come to explain it to you,

ma chère

Marie.”

***

At the age of nine months I was carried in a great procession to the royal chapel at Stirling Castle and crowned Mary Stuart, queen of Scotland, in a solemn ceremony. I remembered none of it, of course, but the event was described to me so oftenâhow I reached out and tried to grasp the scepter; how I did not stop wailing throughout the ceremonyâthat in a few years I came to believe I actually

could

remember it all.

I was barely a year old when the Scottish Parliament signed an agreement with England declaring that when I reached the age of ten I would marry Prince Edward, the son of King Henry VIII. I was pledged to marry the “auld enemy”! That promise was not enough to satisfy King Henry. He demanded that I come to live in England until my marriageâfor my safekeeping, he said. My mother refused to allow it. Fearing that King Henry would have me kidnapped, my mother moved me from Linlithgow Castle, where I was born, to Stirling Castle, far north of the border and better fortified against an English attack. But still my mother did not feel easy. We moved again, to an even more remote castle.

While we were there, news came from England that Henry VIII had died. Nine-year-old Edward was the new king. I was four.

“I am certain it is safe now,” said my mother. “We can go home to Stirling.”

But she was wrong. The English continued their attacks along the border. They mowed down ten thousand Scots in the Battle of Pinkie Cleugh and began the march to Stirling. In the dead of night my mother and I were bundled onto a litter and carried to an Augustinian priory on a quiet lake far from the smoke and noise of battle. Within a few days the Four Maries and their mothers joined us on the island of Inchmahome. I would have happily stayed on that pretty island, unaware of the bloody fighting that still raged, chasing butterflies, gathering eggs from the hens' nests, and devouring the rich buns the monks baked for us every morning.

My mother now made a decision that would determine the course of my life: Instead of marrying Edward, the new king of England, I would marry the future king of France. But the future had its beginning in the present. “Until you are old enough for marriage, you will live at the French court and learn their language and their ways,” said my mother. “Someday the king's son, the little dauphin, will become king, and you will be queen of France.”

“What is the laddie called?” I askedâmy first question.

“His name is François de Valois. He is four years old, a little younger than you.”

“You are coming too, are you not, Maman?” I asked.

“Non,

Marie,” she said. “I must stay here. But your nurse and your governess will go with you, and Lord Erskine and Lord Livingston as your guardians, and the Four Maries, and your three Stuart half brothers, and many others who know and love you. When you arrive in France you will have your grandparents and your uncles to look after you, and the king of France and his children will welcome you into their family. You will not be lonely, MarieâI promise.”

“Then you will come later,” I insisted stubbornly.

“Oui,

my darling child,” she said, smiling. “Later.”

Her smile was a lie. I sensed the tears behind it, ready to pour again at any moment. I knew without asking that once I left Scotland, my life would change. I could not possibly imagine how much.

***

To prepare for my departure for France, we moved again, this time to Dumbarton Castle, in the far west of Scotland. The ancient fortress was built high on a rocky mound where winds howled and rains lashed, and no English soldier would dare scale the steep rock face that jutted straight up from the water and overlooked the Firth of Clyde, where the river joined the sea. To avoid the English ships, the French fleet had taken a long and dangerous route to reach me, sailing around the northern end of Scotland before heading southward to Dumbarton.

I hated to see my mother weep, but on the day those French ships appeared in the firth, I was too filled with excitement to be overly concerned. The king of France had sent his ships to fetch me! I was going to marry the king's son, and one day I would be the queen of France! I loved the sound of that:

queen of France.

Even my mother did not have such a splendid title. While my father was alive, she had been titled the queen consort of Scots. Now she was known as the queen mother, meaning that her husband, the king, was dead and she was in charge of things in the kingdom until I, her child, was old enough to rule as queen of Scots.