A History of Britain, Volume 3 (42 page)

Read A History of Britain, Volume 3 Online

Authors: Simon Schama

By Dalhousie’s day Lucknow, once one of the most gregarious and socially mixed cities of India, was becoming more divided between its native and Western quarters. But it was still nothing like so sharply segregated as Calcutta, with its ‘black town’ and white riverside villas with gardens, or as Madras. At Lucknow, the packed, old city stretched south from the Gomti river with the

ganj

market bazaar at its centre; each of its districts marked, as it is to this day, by a specific community of artisans – silversmiths, millers and bakers, and tanners. The town houses of courtiers and nobles, the mosques and pleasure gardens were mostly situated at the southern and western rim of the conurbation. And at the northern edge, separated by a little clear ground and the beautiful Kaiserbagh garden, was the 34-acre compound of the Residency, raised on a small plateau. At its heart was the Residency itself, built in thick, dusty rose brick, with Doric columns, a verandah, a little flag tower and a cool underground swimming bath. Scattered about the gardens were a church, post office, treasury, the financial commissioner’s house and the Begum Kothi, which had once been the quarters of the nawab’s European wife. The cantonment proper, with its barracks and bungalows and racecourse, were some miles off, north of the Gomti and the Faizabad road. Further to the west was the prodigious neo-Baroque pile of a school known as La Martinière, designed and endowed by the French soldier of fortune and hot-air ballooning polymath Claude Martin, who had served the nawabs and then the East India Company. The school was now the epitome of the Macaulay educational mission, drilling its

pukka

schoolboys in Thucydides, Milton and musketry.

This division of zones, although clear, still put the centre of British life – the Residency – very much inside, rather than outside, the city itelf. Historically this was precisely because the Residents had always claimed an unusual degree of comfort, living amidst the native community. Under the current Resident, Sir William Sleeman, in the early 1850s, the familiar, rather easy-going cooperation by which the British expected to get

no

trouble from Awadh (and recruit a lot of sepoys) seemed to be working well enough still to make any drastic alteration unnecessary. With Whig governments taking flak from liberals like Richard Cobden for promoting expensive, ‘cruel’ and needless imperialist adventures, and with wars under way in southern Africa, China, Burma and the Crimea, the last thing that Britain needed was to provoke another in India.

But of course Dalhousie – who bequeathed the forthcoming disaster to his successor, Charles Canning – hardly saw the danger coming. As far as he was concerned, a pseudo-independent Awadh, barely governed at all (in his view) by a joke nawab, Wajid Ali Shah (whose proudest boast was his success at breeding a pigeon with one white and one black wing, and who was notorious for spending his days trying on jewellery, writing poetry and reposing with his courtesan of the week), was not just a luxury but a danger. Had not the foreign secretary to the Governors Council, H.M. Elliot, the posthumous author of

The History of India, As Told by Its Own Historians

(1867), pointed to the ‘evil’ of tolerating such iniquitous maladministration? ‘We behold’, Elliot had written, ‘kings, even of our own creation, sunk in sloth and debauchery.’ Time, then, to unmake them. ‘The British Government’, Dalhousie wrote, ‘would be guilty in the sight of God and Man, if it were any longer to aid in sustaining by its countenance an administration fraught with evil to millions.’ Besides, Dalhousie relished the contribution its revenues would make to cutting the £8 million deficit that his military adventurism in the Punjab had incurred. When he heard that the nawab and his ministers were being ‘bumptious’ he confessed in private that he hoped this was indeed the case, since ‘To swallow him before I go would give me satisfaction.’ In February 1856, despite a journey to Calcutta by Wajid Ali Shah and his chief ministers to plead personally with the Governor-General, Awadh was duly annexed. Dalhousie wrote, scarcely concealing his pleasure, that as a result of the annexation ‘Our gracious Queen has five million more subjects and one point three million pounds more revenue than she had yesterday.’

What might have seemed almost a bureaucratic decision in Bengal set up immediate shock waves in both the towns and countryside of Awadh. Overnight an entire population that had served the court and nobility of the kingdom was, in ways barely discernible to the sahibs, not just demoted but shamed. Spilling back into the countryside, they found another crucial class of influential Awadhis – the

taluqdars

, sometimes also known as rajahs, who were hereditary owners of land-tax jurisdictions, which, as elsewhere in northern India, carried with them a bundle of manorial rights and obligations – summarily dispossessed of many of their villages, lands and titles. The official British idea – already implemented in

Sind

and the Punjab – was that something as important as the land tax (which paid, of course, for the huge army) should be directly administered and not left to village notables, invariably (and inaccurately) described as ‘intermediaries’, to cream off profits and perks while bleeding the peasants dry. These ‘intermediaries’ were classified, in the bureaucratic mind of British officials, as somehow alien to the villages; whereas in fact their title, status and authority went back many generations into the Mughal past, when Rajput warriors had been assigned districts and villages for their support. In some cases the ‘rajahs’ were themselves not much more than village farmers and, through clan and caste connections, lived very close to the peasant communities.

The British assumption was that since, in many cases, the amount of revenue they were taking would be less than under the old

taluqdar

system, they would receive the devoted gratitude of the farmers. But the Awadh countryside turned out to be a poor experimental study for the utilitarian measurement of pain and relief. The

taluqdars

and rajahs had always been far more than tax collectors: they were manorial, godfatherly patrons, surrounded by personal militia whom it was still an honour to join. Established in their

kutcha

mud or

pakka

gravel-and-cement trench forts deep in the jungle, with rifles and light field guns, they were very definitely the power in the land. And that power was not, as the superficial British inquiries had it, a one-way exploitation. In return for the taxes they received in money and kind from the peasants, the

taluqdars

oversaw the life of their villages; helped the destitute in times of dearth; smoothed out marriage arrangements and disputes; and patronized local mosques and temples. Sometimes they helped with the harvest themselves. Their summary dispossession was not, then, the removal of an obvious anachronism; it was a culture shock that rippled down all the way to local markets, mosques and villages. It made the intruding company

bahadur

(governor) seem crass, brutal and demonstrably alien. When the smoke cleared from the 1857 rebellion, many British professed their amazement that, instead of remaining loyal or at least neutral, the peasantry in tens of thousands followed their rajahs and

taluqdars

into resistance. But for both sets of Awadhis, Muslim and Hindu, it was the most natural thing in the world.

Many of those

taluqdars

and peasant families, of course, had brothers and sons who were sepoys; and who with the disappearance of Awadh had now lost the status they had enjoyed as ‘seconded’ men, not to mention their double

batta

. Well before the cartridge-grease debacle, there had been many acts of tactlessness that had put a strain on the loyalty of the army rank and file. High-caste soldiers, for whom travel by sea was a taboo, had been threatened by the loss of their caste when ordered to ship

to

the Burma front to serve in one of Dalhousie’s endless wars. Informed of their objections, but also of the men’s willingness to march to Burma, the Governor’s response was, ‘Oh they are fond of walking, are they? They shall walk to Dacca, then, and die there like dogs.’ (And so they did.) Humiliating corporal punishments, especially flogging, stood in stark contrast to the care taken in earlier decades not to inflict acts of public shame on men for whom loss of respect was the most mortifying of all disgraces. In the charged atmosphere that Dalhousie had chosen to ignore – but that the more alert incoming Governor-General, Viscount Canning, thought heralded trouble – rumours flew that the

attah

, rations of flour, ground in the company’s new mill near Kanpur (Cawnpore), contained pulverized human bones from corpses collected on the banks of the Ganges and was yet another fiendish plot to defile the purity of both Muslims and Hindus. Not all these shocks were fantasies. In Jhansi, the elimination of the independent state was followed by the mass slaughtering of cattle, a direct cause of uprisings near the fortress city of Gwalior.

The issuing of the new Lee-Enfield rifles with greased cartridges that needed the ends to be smartly bitten off before being inserted into the breech was not, of course, a deliberate provocation. It was precisely the casually unintentional nature of the offence that was so typical of the modus operandi of the Dalhousie era. No one in fact seemed to know whether the offending grease was pork fat, beef tallow or a mixture of the two, thereby outraging both Muslims and Hindus. As soon as the blunder was acknowledged, it was corrected by having cartridges lubricated with vegetable oil. But the damage had already been done. (At Meerut on 9 May the cartridges were not in fact greased with animal fat, but since there was no way for the sepoys to be certain they were not prepared to risk defilement; it was a moment that defined the collapse of trust between officers and men.) To their cost, the British tended to discount the kind of information the telegraph was not equipped to pick up: rumours and prophecies. One of them, circulating in the bazaar at Lucknow and Delhi predicted that the Company’s rule would last no more than precisely the century from the date of the battle of Plassey – 23 June 1757. Cryptic messages to native regiments in the cantonments were relayed through torn chapattis and lotus flowers.

Within weeks of the outbreaks at Meerut and Delhi, British military power seemed to have collapsed in the Ganges valley. The news that the reign of the English was over carried the spark from the Bengal army to the towns and villages of the northwest provinces, Awadh and northern Rajasthan. At Lucknow the sepoys mutinied on 30 May. At Gonda military station, 80 miles north of the city, Katherine Bartrum, a Bath

silversmith’s

daughter of 23 who was living the bungalow life along with her husband Robert, assistant surgeon in the army, and their 15-month-old son Bobby, began to notice an ominous change in the attitude of their servants. Quite soon the punkah wallahs, gardeners, stewards, cooks,

chokidar

watchmen and ayahs started to disappear, and with them went the world Kate Bartrum had thought would last for the rest of her Indian life: ‘I think we have all become fearfully nervous,’ she wrote anxiously to her father. ‘Every unusual sound makes one start; for who can trust these natives now, when they seem to be thirsting for European blood?… For many nights we had scarcely dared to close our eyes. I kept a sword under my pillow, and dear R. had his pistol loaded ready to start up at the slightest sound, though small would have been our chance of escape had we been attacked …’

As the situation suddenly deteriorated, and news arrived of the mutiny at Lucknow and the carnage at Meerut and Delhi, as well as the unlikelihood of immediate British troop reinforcements, Robert knew that Kate’s best chance of survival was getting her and the baby to the relative safety of the defensible Residency compound. At Secrora, 65 miles from Lucknow, they were told there would be a small military detachment to take them and other women and children who were stranded in the country, to the Residency. But they had to get there first. Robert, Katherine and the baby set off together with a Mrs Clark and her husband and small child, all on the backs of elephants, but when they got to Secrora the military escort, worried about time, had already left. The men were needed at their regiments, so, after terrible agonizing, the two women, with a small group of loyal sepoys, made their own way, in temperatures of well over 100°F, through what had suddenly become the hostile country of the rajah of Gonda (as it turned out, one of the most militant rebels) to the domes and minarets of the ‘Golden City’.

They reached the safety of the Residency on 9 June, but even so it was clear that there would no easy salvation. By the end of the month, 8,000–10,000 sepoys, including 700–800 cavalry, had ringed the Residency defences. Two-pounder rebel batteries were soon in full action, along with 12 other field-gun emplacements, which kept up a steady barrage on the compound. Shallow trenches had been dug immediately behind the guns, in which the gunners could lie and still operate the cannon while being virtually invisible to defending counter-fire. Inside the walls were just 1700 male defenders – 800 British troops, 700 loyal sepoys, with the remainder drawn from the civilian and merchant colony including 50 schoolboy cadets from La Martinière. The chief commissioner of Awadh, the veteran military commander Brigadier-General Sir Henry Lawrence, was already seriously ill and quarrelling with the financial commissioner, Martin Gubbins, about whether to keep or send away (without arms) the sepoys inside the Residency. Gubbins, the pessimist, was for getting rid of them.

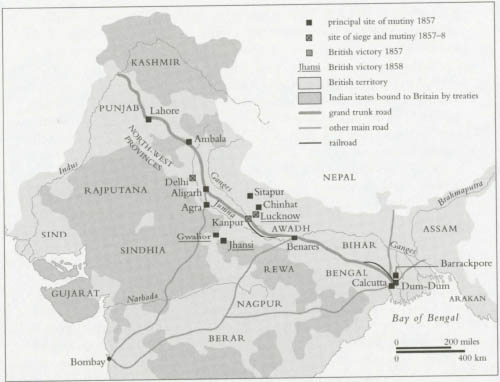

The Indian Mutiny, 1857–8.