50 Children: One Ordinary American Couple's Extraordinary Rescue Mission into the Heart of Nazi Germany (6 page)

Authors: Steven Pressman

Tags: #NF-WWII

Between March 1938 and March 1939, nearly half of the city’s Jewish population had departed. The vast majority had hoped to immigrate to the United States, especially since so many of them had relatives already living there. But America’s immigration laws created an insurmountable obstacle for most German and Austrian Jews seeking safe haven in the United States. First, fixed quotas capped the number of immigrants from every foreign country, resulting in a long waiting list for tens, if not hundreds, of thousands of Jews. Second, America would only admit refugees who were able to guarantee that they would not require any sort of public assistance once they arrived. Stymied by the United States’ closed-door policies, many of Vienna’s Jews instead dispersed to other far-flung corners of the earth—Shanghai, Havana, Buenos Aires, and elsewhere. A few even managed to sneak into Palestine despite the strenuous efforts of the British authorities to prevent more than a trickle of Jews from legally entering the Holy Land and disrupting the fragile Arab-Jewish balance that His Majesty’s government was vigorously attempting to maintain.

From the earliest moments of the Anschluss, newspapers and magazines throughout the United States and the rest of the world were filled with detailed accounts of Hitler’s takeover of Austria and what it meant for the country’s Jews. “Their fate is even worse than that of the Jews in Germany, where the persecutions were spread over a period of several years,” the

New Republic

magazine informed its readers in April 1938, only weeks after the Anschluss. “In Austria, the full force of the sadistic Nazi attack has come overnight.” Hitler’s Nuremberg laws, which had gradually stripped German Jews of their civil rights over a period of five years, were instantly put into effect. Hermann Göring, Hitler’s field marshal, had wasted no time in issuing a blunt warning that Jews were no longer welcome anywhere in Austria. Vienna, he announced, would become purely German again. “The Jew must know we do not care to live with him. He must go,” Göring told foreign journalists. Throughout Vienna, groups of Jewish men, pious rabbis among them, were forced to scrub clean the few anti-Anschluss symbols that had been painted on streets and sidewalks prior to Hitler’s arrival. Newly emboldened members of the Hitler Youth organization set out across the city, taunting and terrorizing Jewish shopkeepers and whitewashing swastikas, skull and crossbones, and

Jude

across their storefront windows.

Within days of the Anschluss, in an early morning raid that was carefully planned well in advance, the Gestapo shut down the Israelitische Kultusgemeinde—Vienna’s official Jewish community office—and arrested the organization’s president, two vice presidents, and executive director. Six weeks later—on May 3, 1938—Adolf Eichmann, a thirty-two-year-old SS lieutenant who had been dispatched to Vienna to plan and enforce the

Judenrein

policy, officially permitted the Kultusgemeinde to reopen and released some of the arrested leaders. But Eichmann had only one purpose in mind for Vienna’s Jewish leaders: to help him carry out the removal of every Jew—man, woman, and child—in the city. By the summer of 1938, more than twenty thousand people had made their way to the Kultusgemeinde’s headquarters at No. 2 Seitenstettengasse, where they often had to wait for hours to officially register for emigration papers. Long rows of wooden filing cabinets on the second floor of the building, located only a few blocks from the Gestapo’s headquarters at the Hotel Metropole, spilled over with thousands of cardboard index cards that meticulously listed Jewish families desperate to leave Austria as soon as possible. Eichmann and other Nazi officials were determined to fulfill Hitler’s dream of a

Juden

-free Germany and Austria. Only one question remained: Where would all those Jews go?

The visa section at the American consulate office in Vienna was overrun with applicants hoping to gain admission into the United States. Long lines of people would form early each morning, anxiously waiting for the consulate to open its doors at 9:00

A.M.

The overworked staff would often remain at their desks until 10:00

P.M.

, seeing as many as six thousand people and conducting up to five hundred interviews each day. Given the limited number of spaces allotted to Germany and Austria, the consulate officers knew that most of the individuals and families who were pleading for visas would have to wait as long as five years before their turn would come up.

To help expedite the forced Jewish exodus, Eichmann had set up the Zentralstelle für Jüdische Auswanderung—the Central Bureau for Jewish Emigration—which established, in a highly bureaucratic and assembly-line manner, a brutally efficient process for ridding Austria of Jews. Eichmann also found—or rather, annexed—what he considered to be an ideal location for his Zentralstelle. The ornate palace that occupied a full city block at No. 22 Prinz Eugenstrasse had, until recently, been the home of Albert Rothschild, a member of the Vienna branch of the famous European Jewish banking family. Designed in the French neo-Renaissance style, the imposing nineteenth-century building—one of five palaces belonging to various Rothschilds who lived in Vienna—was set back from the street, with a courtyard and a U-shaped layout. The entrance hall led to an enormous marble staircase, and throughout the building were crystal chandeliers, gold leaf, and polished parquet floors.

On August 20, 1938, Josef Bürkel, who had been installed as the Nazi gauleiter in Vienna after the Anschluss, spelled out the new function of the Rothschild palace in a memo sent to all Nazi state and party offices throughout Austria. “Undesirable interruptions and delays have occurred in the emigration of Jews. In addition, the question of Jewish emigration has been dealt with inefficiently by certain offices,” wrote Bürkel. “To assist and expedite arrangements for the emigration of Jews from Austria, a Central Office for Jewish Emigration has therefore been set up in Vienna, at Prinz Eugenstrasse 22.”

Eichmann and other Nazi officials took enormous satisfaction in converting the Rothschild mansion into a one-stop facility for hastening the fulfillment of

Judenrein

. “This is like an automatic factory, let us say a flour mill connected to some bakery. You put in at the one end a Jew who still has capital and has . . . a factory or a shop or an account in a bank,” Wilhelm Höttl, an SS officer who served under Eichmann, later recounted. “He passes through the entire building, from counter to counter, from office to office. He comes out the other end. He has no money, he has no rights, only a passport in which it is written: you must leave this country within two weeks. If you fail to do so, you will go to a concentration camp.”

I

N THE WAKE

of the Anschluss, even the youngest Jews felt the sense of peril that had descended over the city. Elizabeth Zinger was five years old and had recently started kindergarten. Sitting quietly in her classroom one morning, the little girl raised her hand, trying to get her teacher’s attention so that she could request permission to go to the bathroom. The teacher, however, continued to ignore her, even as it became obvious why she wished to be excused. Finally, Elizabeth could not wait any longer, and she wet herself. Her teacher shot her a scolding look and grabbed the frightened girl by the collar of her blouse, pulling her out of her chair and in front of the rest of the class. “You see. This is what the

Juden

do. They make in their pants,” the teacher announced to the other students, after which she shoved the sobbing girl back into her seat. “After that horrendous experience, my mother didn’t send me back to school,” Elizabeth remembered, “which was just as well, because very shortly thereafter it was announced that I could not come back. Nor could my sister—and all because we had committed that terrible crime of being Jewish.”

Jewish children all throughout Vienna quickly learned to live in fear of the Nazis and their sympathizers. Kurt Herman’s path literally intersected with Hitler’s celebrated arrival in Vienna. At the age of seven, he was walking with his mother across a bridge that spanned the Danube Canal, not far from their home in the city’s Second District. Suddenly a long motorcade of black cars, each adorned with a small red swastika flag that flapped in the breeze, rumbled through the streets, passing directly in front of Kurt and his mother. Standing in the backseat of one of the cars was the German chancellor, who would repeatedly thrust out his right arm in a gesture that, even at his young age, Kurt recognized as the Nazis’ salute. The young boy stood there, motionless. Everyone around them was cheering loudly and waving their arms in enthusiastic salutes. The young boy and his mother, worried about standing out in the crowd, timidly held out their arms as well.

A few weeks after the Anschluss, Robert Braun walked into his fourth-grade classroom at the Schubert Schule and took his usual seat at a desk in the middle of the room. All of the other boys began filing in as well and then waited for their teacher to quiet them down—not an easy task for a classroom filled with rambunctious ten-year-old boys. Robert noticed that a yellow line had been painted in front of the last row of seats in the room. After all of the boys had arrived, the teacher stood up in front of the class and began speaking in a somber tone. “The authorities have ordered that we rearrange the seating in the room,” the teacher announced. He pointed to the yellow line on the floor and proceeded to call out the names of all of the Jewish boys in the class. From now on, he said, they were to sit in the row of seats behind the yellow line. In the weeks that followed, some of the boys in the class began showing up at school in outfits that Robert had come to recognize as the Hitler Youth uniform—dark-colored short pants, khaki-colored cotton shirts, knee-high white stockings, and red armbands emblazoned with black swastikas. He quickly learned to steer clear of those boys as best he could, although sometimes they would chase him, taunt him, or try to throw punches at him. One of them hurled a small rock. It left a scar across his scalp that would still be visible seventy-five years later.

On March 13, 1939—precisely one year after the Anschluss—the Vienna correspondent for the Jewish Telegraphic Agency filed a story that cited a depressing litany of statistics about the rapid disintegration of Vienna’s once-vibrant Jewish community. During the previous twelve months, 7,856 businesses had been “Aryanized”—that is, Jewish owners had been forced to hand their business over to new Aryan owners for little, if any, compensation. Another 5,122 Jewish-owned businesses had simply gone bankrupt. More than 12,000 Jewish families had been summarily evicted from their apartments, and almost all of the city’s Jews had been herded into the already congested Leopoldstadt district, essentially creating a Jewish ghetto. Thousands of Jewish men had been arrested and sent to concentration camps located in unfamiliar places with names such as Buchenwald and Dachau. While these places had not yet given way to the death camps of the Final Solution, there had already been reports of the ashen remains of some of the men—husbands, fathers, uncles, grandfathers—being returned to relatives in Vienna following their unexplained deaths while incarcerated.

Our apartment was visited by the Brown Shirts, who were the bully boys of the Nazi Party. They looked in every room and in every closet for an adult. My father never came home from work that night

.

—E

RWIN

T

EPPER

V

IENNA

N

OVEMBER

1938

O

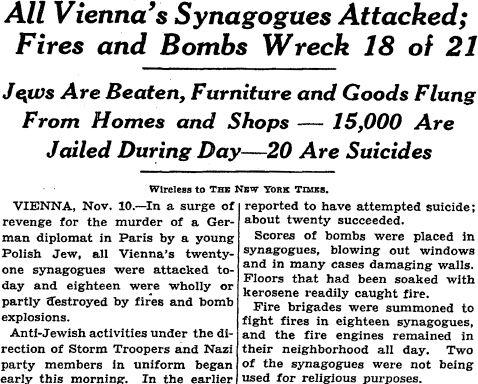

n the morning of Monday, November 7, 1938, seventeen-year-old Herschel Grynszpan carefully loaded a handful of bullets into the chamber of a revolver that he had purchased the day before and then walked from his uncle’s apartment, where he had been staying, to the German embassy in Paris. Ten days earlier, Herschel’s parents—along with thousands of other Polish Jews who had been living for years in Germany—had been arrested, their homes and property taken away from them, and packed into trains that left them stranded near the Polish border town of Zbaszyn. Grynszpan’s father had managed to mail a postcard to his son, pleading with Herschel to do whatever he could to help the family. Upon arriving at the German embassy, Grynszpan asked to see an official, explaining that he had an important document to deliver. Moments later, he pulled out his revolver and unloaded the bullets into the abdomen of Ernst vom Rath, a twenty-nine-year-old low-level embassy officer. The mortally injured German was rushed to a nearby hospital while the Jewish teenager quickly surrendered himself to the French police. In his pocket was a postcard that he had written to his parents, lamenting what had happened to them and the other Jews trapped in Zbaszyn. “May God forgive me,” he wrote. “The heart bleeds when I hear of your tragedy and that of the 12,000 Jews. I must protest so that the whole world hears my protest, and that I will do.”

Nazi leaders in Berlin wasted no time in reacting to Grynszpan’s desperate act. One day after the shooting, the authorities banned all Jewish children from attending public schools and suspended the publication of all Jewish newspapers throughout Germany and Austria. Within hours of vom Rath’s death from his injuries on November 9, Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s propaganda minister, set in motion a violent retaliatory pogrom—he described them as “spontaneous demonstrations”—aimed against all Jews throughout the Reich. Shortly after midnight that evening, Reinhard Heydrich, the deputy head of the Gestapo and the SS, sent a top secret telegram to police officials throughout Nazi Germany that laid out the guidelines for the riots that had already broken out against the Jews. Heydrich made it clear that the police were not to interfere with rioters. He also ordered the immediate arrest and detention of “healthy male Jews who are not too old,” who would later be transferred to concentration camps.