50 Children: One Ordinary American Couple's Extraordinary Rescue Mission into the Heart of Nazi Germany (9 page)

Authors: Steven Pressman

Tags: #NF-WWII

On Friday, February 3, shortly after their meeting in Washington, Gil typed out a two-page letter to Messersmith that described the general outline of the Brith Sholom plan to bring fifty Jewish children from Germany to the United States. Gil again assured Messersmith that there would be no attempt to circumvent the immigration laws or the existing German quota. “We will supply satisfactory affidavits and guarantees from individuals of good standing and character to fulfill the public charge requirements. Each child shall have his own affidavit,” wrote Gil. He also reminded Messersmith that there were “ample private funds to provide transportation of the children from Germany to Philadelphia and for their support, maintenance and education.” Gil’s letter further explained his own role—and that of Eleanor’s—in the unfolding rescue plan. “To accomplish our purposes as promptly as possible, Mrs. Kraus and I are prepared to go to Germany to arrange with the proper governmental authorities for the selection of eligible children, the filing of the affidavits, and the transportation of the children.” He closed the letter with a request that Messersmith offer some word in reply “concerning the feasibility of our plan and news from Germany.”

On the same day that Gil wrote his letter to Messersmith, the State Department official sent a two-page cable to Geist in Berlin. The cable began with a reminder that “all sorts of steps are being proposed to bring children into this country in various ways.” Messersmith mentioned that several bills were expected to be introduced in Congress that would allow for children living in Nazi Germany—Jewish and otherwise—to be admitted into the United States above and beyond the quota limits. “My own view is that all these bills will probably die if they are introduced,” Messersmith candidly told Geist. “Although I am generally sympathetic to the idea of the admission of children under 15 years of age in a certain number . . . I believe the administrative difficulties in carrying through such a mission are tremendous and perhaps insuperable.” Besides, he added, debating any kind of immigration legislation “is going to raise discussion which we want to avoid.” Messersmith, above all else, was a political pragmatist who was well aware that anti-immigrant members of Congress would seize on any excuse to restrict immigration even further.

Without mentioning Brith Sholom by name, Messersmith’s cable referred to “a responsible group” that was hoping to bring in children “under the quota whose parents for some reason or other may not be able to emigrate.” In order to determine whether the plan might work, “a man and a woman of this organization intend to go to Germany and talk over certain matters with you and to go into certain aspects of the problem.” Gil and Eleanor were both Jewish, he explained to Geist, but “I told them that I did not see any reason why an American Jew or Jewess should not go to Germany on such legitimate business and I did not believe that they were running any special risk in so doing. As to whether a Jew or Jewess could find a proper hotel to stay in, I was uncertain and that I would write you.” Messersmith ended his cable with a request that Geist reply with either a “voyage feasible” or “voyage not feasible” response.

Three days later, on February 6, Messersmith sent a letter to Gil saying that he thought Brith Sholom “thoroughly understands our immigration laws and practice” and that Gil’s proposed plan “is, I believe, the only sound and feasible way to approach this problem.” But, as he had emphasized during the meeting, Messersmith stressed that “there is nothing which this Government or this Department can do which involves sponsoring any such procedure.”

Messersmith was willing, however, to take quieter steps aimed at giving at least an unofficial nod of approval to the rescue effort. Not long after his meeting with Gil, Messersmith sent a memo to A. M. Warren and Eliot Coulter, the senior State Department officials in charge of the visa division. “I believe that this group is a responsible one and they do seem to be a sensible one,” Messersmith wrote. “They have made a very favorable impression on me and their one thought is to carry through this project, which involves the initial bringing in of some 50 children, completely within the framework of our present immigration laws and practice.” He sent a similar message to Geist in a second cable to Berlin that described the Brith Sholom plan in more detail. “They have approached this whole problem in a much more sensible and understanding way than most people. I think you may give any representatives of this organization, whose names I would eventually send you, full cooperation within the framework of our existing immigrations laws and procedure.”

Two weeks later, on Monday, February 20, Messersmith received a telegram from Geist. It simply said: “Voyage entirely feasible.”

What is American citizenship worth if it allows American children to go hungry, unschooled and without proper medical attention while we import children from a foreign country? Let the sympathies of the American people be with American children first

.

—S

ENATOR

R

OBERT

R

EYNOLDS OF

N

ORTH

C

AROLINA

W

ASHINGTON

, D.C

.

F

EBRUARY

–M

ARCH

1939

O

n the morning of Thursday, February 9, 1939, Senator Robert Wagner, a Democrat from New York, rose to his feet next to his polished mahogany desk in the chamber of the United States Senate. After being recognized, Wagner announced the introduction of a bill he had authored that, if enacted, would dwarf the plan that Gil had been discussing with George Messersmith at the State Department.

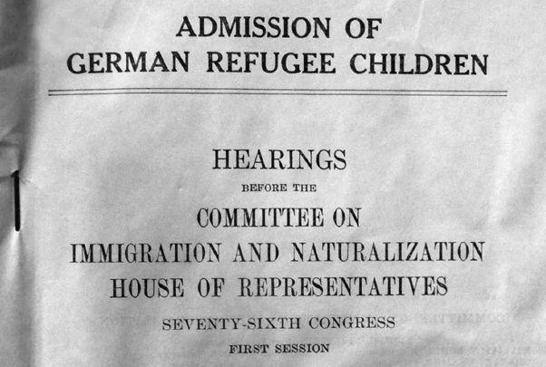

Wagner, who had been elected to the Senate in 1926 after spending several years as a New York state legislator and judge, knew firsthand what it meant to be an immigrant looking to America for safe haven. As a young boy, he and his parents had come to the United States from Prussia (which later became part of Germany) and settled in New York City’s Yorkville neighborhood. After attending the city’s public schools, Wagner enrolled in the College of the City of New York (which later became City College) and later earned a law degree from New York Law School. While serving in the New York State Senate, he led a committee that investigated the tragic Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, the 1911 disaster that claimed the lives of 146 garment workers, most of whom were young Jewish or Italian immigrant women. Throughout his political career Wagner remained a steadfast supporter of immigrant rights. By early 1939 he had been working on his children’s rescue measure for weeks, aided by refugee relief groups and influential individuals. Wagner’s bill—formally known as Senate Joint Resolution 64—would allow twenty thousand children from Germany to enter the United States over the next two years, above and beyond the existing German immigration quota. “Millions of innocent and defenseless men, women and children in Germany today, of every race and creed, are suffering from conditions which compel them to seek refuge in other lands,” Wagner said as he introduced his bill. “Our hearts go out especially to the children of tender years, who are the most pitiful and helpless sufferers.” Passage of his bill, he added, would provide them with much needed relief “from the prospect of a life without hope and without recourse, and [would] enable them to grow up in an environment where the human spirit may survive and prosper.”

Five days later, Edith Rogers, a Republican congresswoman from Lowell, Massachusetts, proposed identical legislation in the House of Representatives. “In Germany you have the situation where families . . . are willing to have their children come to a place where they feel they are safe,” said Rogers, who had been one of the first members of Congress to take up the cause of Jewish victims of Nazism. “I have also had the hope that many of the children would go back to their parents later. I do not feel that Hitler will always be in power in Germany.”

The Wagner-Rogers bill at least in part was inspired by the British government’s decision in late 1938 to ease its immigration rules and allow thousands of Jewish children into England. Jewish leaders in Britain delivered an urgent personal appeal to Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain five days after Kristallnacht, which resulted in Parliament’s swift approval of a bill that waived immigration requirements for children under the age of seventeen, who would be permitted to live, at least temporarily, with British foster families. The first group of nearly two hundred children left Berlin on December 1, 1938, and arrived in England the next day. Over the next nine months, some ten thousand children—most of them from Germany and Austria—were evacuated to safety in England, sent away on trains and crossing the English Channel in boats that, collectively, came to be known as the

Kindertransport

.

Within weeks of the introduction of the Wagner-Rogers bill, scores of newspapers around the country published high-minded editorials in favor of allowing the twenty thousand children into the country. “It is difficult to see how anyone with humanitarian impulses can oppose” the bill, declared Virginia’s

Richmond Times-Dispatch

. “Those of us who have enjoyed a normal and happy childhood should try to place ourselves in the position of these unfortunate boys and girls in the Germany of today, where they are treated as outcasts, scoffed at in public, and in many cases thrown out of orphan asylums and left on the verge of starvation. How can we, who profess to believe in democracy and human rights, sit idly by and allow such atrocities to be committed without raising a finger?”

But many of these same editorials, while lauding the humanitarian impulse to help Jewish children, also lobbied in defense of America’s existing immigration quotas. These editorials made it clear that a special gesture to aid the children should not be viewed as an endorsement of a broader effort to liberalize the nation’s overall immigration laws. “It is impossible to offer sanctuary in this country to all refugees, however urgent their need,” maintained the

Galveston News

in an editorial published on February 20. “It would dishonor our traditions of humanity and freedom, however, to refuse the small measure of help” offered by the legislation.

These sentiments were broadly echoed in public opinion polls, which reflected overwhelming opposition to any relaxing of the immigration laws, even in light of the events unfolding in Europe. A 1938 survey conducted by the Roper polling company found that fewer than 5 percent of Americans favored more liberal immigration quotas. The same survey revealed that more than 67 percent of Americans were willing to stop all further immigration into the United States. The United States still bore the scars of the Great Depression, and restricting immigration was seen as a way to protect jobs for Americans, who for years had been plagued with staggering unemployment rates. But challenging economic considerations were not the only factors at play in the immigration debate. The American public simply was not moved by the dire situation in Europe.

Even 20 percent of American Jews said they favored a strict immigration policy. Many feared that efforts to allow more than a small trickle of Jewish refugees into the country would only add further fuel to the rising flames of anti-Semitism in the United States. Jewish leaders worried that any effort to liberalize the immigration quotas would quickly be interpreted as un-American, resulting in even more negative attitudes toward the country’s Jewish population. These fears were not unfounded. A series of public opinion polls conducted in the late 1930s found that 60 percent of Americans held a low opinion of Jews, regarding them as “greedy,” “dishonest,” and “pushy.” More than 40 percent believed that Jews held too much power in the United States—a figure that would rise to 58 percent by 1945. A Roper poll conducted in 1939 revealed that only 39 percent of Americans felt that Jews should receive the same treatment as all other citizens, while 53 percent believed that “Jews are different and should be restricted.” One out of every ten Americans felt that all Jews should be deported outright.

The anti-Semitic rants of national figures such as Father Charles Coughlin—the so-called radio priest of the 1930s—further inflamed public attitudes against Jews during this period. Throughout the Great Depression, Coughlin frequently railed against “international bankers”—a long-recognized code phrase for powerful Jewish interests in the United States and Europe. In a national radio broadcast ten days after Kristallnacht, Coughlin offered a twisted explanation of the Nazis’ rise to power in Germany as a logical reaction to Soviet communism, which he and many others felt had been heavily influenced by Jewish leaders: “It is my opinion that Nazism . . . cannot be liquidated until the religious Jews in high places—in synagogues, in finance, in radio and in the press—attack the cause, attack forthright the errors and the spread of communism, together with their co-nationals who support it.” In the same speech, Coughlin insisted that any potential danger to 600,000 Jews in Nazi Germany “whom no government official has yet sentenced to death” paled in comparison to millions of Christians “whose lives have been snuffed out, whose property has been confiscated and whose altars have been desecrated” since the 1917 Communist revolution in Russia.