50 Children: One Ordinary American Couple's Extraordinary Rescue Mission into the Heart of Nazi Germany (2 page)

Authors: Steven Pressman

Tags: #NF-WWII

Other groups, including several leading Jewish organizations, had been trying since 1934—within a year of Hitler becoming Germany’s chancellor—to bring Jewish children to safety in the United States. Such efforts had yielded very little success, resulting in the rescue of only a small handful of children before bumping up against America’s stringent immigration regulations. No one could figure out a way to bring in larger numbers of children. By the time that Louis Levine left Gil’s office on that January afternoon, Gil knew that he could not possibly turn down the challenge that others had been unable to meet.

Eleanor listened patiently while Gil recounted the conversation with Levine. Drying his face with a small cotton towel she handed him, he told her that Levine was confident that Brith Sholom’s members would readily agree to raise all the money necessary for bringing children over to the United States. Gil glanced at the mirror and then turned toward Eleanor. Levine had asked if he would be willing to take on the project, he said. It would be a very complicated undertaking, of course, but he had promised his friend that he would certainly think it over. For the moment at least, Gil decided not to tell his wife that he had made up his mind on the spot.

Finally, it was Eleanor’s turn to talk. “Gil, this is really crazy!” she exclaimed. “No one in his right mind would go into Nazi Germany right now. It’s not safe, especially for Jews. I’m not sure you could stand it for even twenty-four hours. I’d be too scared to put a foot into that country, assuming the storm troopers would even let us in.” Gil was quiet as he stepped into the bedroom, where he began to dress for dinner. He certainly was not surprised by her reaction. He was fully aware of the risks involved in moving ahead with the rescue plan. Traveling to Nazi Germany held little appeal for a Jew—even one traveling with the protection of an American passport. Gil also knew that the project would almost certainly require him to spend several weeks or even months in Europe. And even then, there was no way of knowing if the plan had any chance of succeeding.

I

N THE WEEKS

and months leading up to Gil and Eleanor’s conversation, the newspapers had been filled with articles that described in grim detail the progressively brutal measures directed against hundreds of thousands of Jews living in Germany and Austria. On January 2, an Associated Press dispatch, which appeared in newspapers throughout the United States and Canada, reported on a New Year’s message from Joseph Goebbels that demanded an international solution to the world’s “Jew problem.” “Germany’s Jews . . . started the new year in dire circumstances,” wrote the AP’s Berlin correspondent. “Emigration, in the face of the Nazi aim to drive all but elderly Hebrews from the Reich, has bogged down in a jam of applications at consulates and in the problem of financing the exodus.” A week later, on January 9, newspapers published a United Press report, also from Berlin, disclosing that hundreds of Jews had recently been brought into Gestapo headquarters, where they were forced to sign pledges to leave Germany or face imprisonment. “Similar pledges were exacted from Jews released from Nazi concentration camps in recent weeks,” the wire service reported, “even though it was impossible for many to obtain foreign visas or enough money to get out of the country.”

Ten months earlier, Hitler’s storm troopers had streamed into neighboring Austria to carry out the Anschluss—Austria’s annexation into the Third Reich. With only token opposition to Hitler’s plan to fold the country into a Greater Germany, the German troops had been warmly embraced—in fact, eagerly welcomed. More than a million cheering citizens of Vienna lined the streets to greet Hitler with flowers, outstretched arm salutes, and thundering shouts of “

Sieg Heil!

” when he triumphantly motorcaded into the city in the late afternoon of Monday, March 14. The following morning, Hitler appeared on a balcony overlooking the vast Heldenplatz, where tens of thousands had gathered to hear him speak. He did not disappoint them. “In this hour I can report to the German people the greatest accomplishment of my life,” Hitler proclaimed. “As Führer and chancellor of the German nation and the Reich, I can announce before history the entry of my homeland into the German Reich.”

The Nazis wasted no time in subjecting Vienna’s 185,000 Jews to the harsh measures that had been directed much more gradually against the 600,000 Jews who lived in Germany. There was nothing secret about these actions, all of which were widely reported in American newspapers. “Adolf Hitler has left behind him in Austria an anti-Semitism that is blossoming far more rapidly than ever it did in Germany,” the

New York Times

reported on March 16, two days after Hitler’s celebrated arrival. “All Jewish executives at Vienna’s largest department store were arrested immediately after Hitler’s arrival, the business being ‘taken over’ by Nazis. Shops, cafés and restaurants were raided and large numbers of Jews were arrested.” Two weeks later, on April 3, a lengthy article in the

Times

described the terrifying new landscape for the Jews of Vienna. “In Austria, overnight, Vienna’s Jews were made free game for mobs, despoiled of their property, deprived of police protection, ejected from employment and barred from sources of relief,” the newspaper informed its readers. “The frontiers were hermetically sealed against their escape.” Within six weeks of the Anschluss, Austria’s new Nazi leaders announced their intention to rid Vienna of all of its Jews within four years. “‘By 1942, Jewish elements must be eradicated from Vienna and must disappear,’ ” the

Times

reported on April 27 in an article that quoted from an editorial published in Hitler’s official newspaper. “‘By that time no business, no factory should be allowed to remain in Jewish hands. No Jews should have an opportunity to earn a living . . . Jews! Abandon all hope. There is only one possibility for you: Emigrate—if someone will accept you.’ ”

The situation for Jews trapped inside Germany and Austria became even more desperate in the weeks that led up to Louis Levine’s meeting with Gil. The November pogrom known as Kristallnacht had completely erased what slim doubts still remained about the Nazis’ aims. Anyone reading the newspapers in America knew exactly what was going on in Europe.

As she pored over these chilling stories, Eleanor had also sensed the dangers that might greet anyone who hoped to do something in response to these tragic events, and she said as much to her husband as they walked downstairs to await their guests. Gil offered little to calm his wife’s anxieties. Instead he frankly explained to Eleanor just how difficult it would be to bring Jewish refugees—even children—into the United States. Labor Department regulations made it impossible for any organization to bring children, unaccompanied by parents, into the country. This meant that Brith Sholom officially could neither sponsor the children’s rescue nor legally act on its own to bring them to America. Although the group might be allowed to house and care for the children once they were here, there was still the challenge of complying with the nation’s strict labor and immigration laws. Gil knew he would have to find another way to bring in children without running afoul of these laws.

Gil spoke with a growing resolve in his voice, which Eleanor recognized. It signaled her husband’s steadfast determination to proceed, regardless of any obstacles that might stand in his way. She shot a wary glance at him, but he cut her off before she could say anything further. She was not surprised when Gil added that he and Levine had already made plans to travel to Washington early the following week in order to meet with officials at the State and Labor departments.

Carlotta Greenfield and her fiancé were due to arrive any moment. Eleanor could hardly imagine how she would make it through the evening with her head spinning with all this talk about Nazi Germany and rescuing Jewish children. Gil, meanwhile, had one more startling piece of information for his wife. If the rescue plan had any shot at succeeding, he would need to round up fifty individual sponsors—one for each child that he hoped to bring back to the United States. Each sponsor would have to fill out an extensive affidavit required by the government to ensure that they would provide sufficient financial support for any immigrant entering the United States. “How would you like to work on this with me?” he asked Eleanor in a voice that was at once both calm and insistent. “It will mean asking our friends and others we know for help. Are you game for that?” Gil figured that it would take several weeks both to find enough people in Philadelphia who would be willing to sponsor the children and to submit the detailed affidavits required by the government. Although he was anxious to begin at once, he told his wife they should wait until he was able to talk to officials at the State Department. “It might all come to nothing,” said Gil. “It may all be impossible.”

B

Y THE MORNING

after the dinner party, Gil seemed even more determined to move ahead. “He said there must be some legal way to bring children into the United States,” Eleanor jotted down in a diary that, years later, she would turn into a private written account about the rescue project. Eleanor knew how much confidence Gil had in his own abilities as a lawyer and also how resourceful he could be when it came to tackling tough problems. Still she tried to avoid becoming too enthusiastic about her own potential role in the mission. “I told myself this going-to-Germany idea was out,” she wrote. “No one, not even Gil, could consider this a practical idea.”

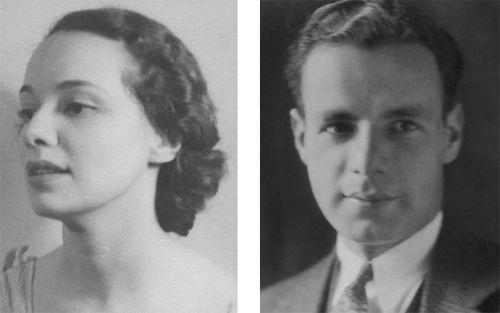

Other considerations stood in the way of Eleanor’s enthusiasm. Only a few weeks earlier, she had talked a friend into offering her a part-time job in the advertising office at the Blum department store on Chestnut Street, not far from the equally fashionable Bonwit Teller and Lord & Taylor stores. Eleanor did not have to work. Gil’s law practice was thriving, and he was more than capable of providing for his wife and two children while keeping the family in upper-middle-class comfort. Eleanor, for her part, embraced the lifestyle that came with the couple’s elevated social standing in Jewish Philadelphia. She was a beautiful woman who rarely hesitated to remind others of her great looks. Having married into the socially prominent Kraus family, she was also mindful of the societal obligations that went along with being Gil’s wife. She was in charge of the couple’s social engagements, while also making sure that the family household ran smoothly. Her dinner parties were always elegant affairs, and she filled their busy schedule with evenings at the symphony, trips to art museums, and leisurely summer weekends at their oceanfront house on New Jersey’s Long Beach Island. Her children attended Friends Select, Philadelphia’s prestigious Quaker school that traced its beginnings back to 1689. Above all else, Eleanor was truly happy being a woman of her time.

Yet as a devotee of fine clothes, jewelry, and fashion, Eleanor was excited about working at the department store and hated the thought of having to give up her brand-new job before it had even started. After Gil’s initial conversation about the plan, she knew, however, that she would almost certainly play a part. She explained to the friend who had offered the job that she might have to leave on short notice in order to help her husband with his work. Although she did not offer details, Eleanor casually mentioned that it might involve travel to Washington and, possibly, to Germany. In the end, the department store job fell by the wayside.

The more Eleanor thought about the project, the more she had to admit that it sounded like something she and her husband should do together. But she also kept reminding herself what an unlikely adventure it would be. “To think of being able to help even a handful of children is a beautiful thought. It is a luxurious dream but most impractical,” she wrote. “After all, we are living a most serene existence in our pretty house on Cypress Street. My own two children seem most secure. Gil is very busy, and his work is going well.”

Over dinner a few nights later, Gil showed Eleanor a couple of affidavit forms he had brought home from his office. The idea of having to ask anyone—let alone her closest friends—to fill out a document with such an exhaustive list of detailed financial questions made her deeply uncomfortable. The affidavits required the applicant to reveal intensely personal information about their income, bank accounts, stock holdings, life insurance policies. Eleanor preferred not to talk about money, and in fact considered the topic virtually off-limits. She rarely even spoke to Gil about the couple’s own finances. How on earth could she even think of asking friends and casual acquaintances to reveal intimate financial details that would almost certainly embarrass them all?

Realizing how awkward this would be for his wife, Gil suggested that she begin by working on his own affidavit. Louis Levine would provide the second one. Once Eleanor grew more comfortable with the process, Gil would give her the names of four or five of his close friends from the Locust Club, the private establishment that served as a social gathering spot for Philadelphia’s most prominent Jewish business, civic, and political leaders. “I don’t think we’re going to have too much trouble finding fifty sponsors,” Gil assured Eleanor. “Everybody wants to help.”

Even as he spoke, Eleanor realized that it was simply a matter of convincing herself—and her circle of friends—that saving children’s lives was more important than concerns about violating social proprieties. Above all else, Eleanor knew that she had to help. It was simply the right thing to do.