50 Children: One Ordinary American Couple's Extraordinary Rescue Mission into the Heart of Nazi Germany (24 page)

Authors: Steven Pressman

Tags: #NF-WWII

After receiving their room keys, Eleanor and Bob threaded their way across the congested lobby, which was humming with the animated conversations of German and Italian military officers. The two Americans stepped into the metal-cage elevator, eager to retreat to their hotel rooms. The elevator operator did not follow them into the cage, however, but hovered just outside, an anxious look on his face. A few moments later, two uniformed men—deep in conversation—entered the cage without so much as a glance at Eleanor or Bob. They continued their conversation while the elevator operator tugged the metal gate shut with a resounding

clang

and swung the lever that set in motion the elevator’s ascent. Eleanor had directed her gaze at the floor when the two men had walked into the elevator car. Now, as the car climbed upward, she looked up. She instantly recognized the two officers—Ciano and von Ribbentrop. Within moments the operator brought the elevator to a stop, pulled open the gate, and waited as the two foreign ministers exited and walked across a hallway onto a hotel balcony, where they stood waving to the crowds gathered on the streets below. It felt to Eleanor like an eternity before the operator pulled the gate shut and set the elevator back in motion.

Gil had a standoff of his own earlier that morning. Having settled the children into the dormitory, he found himself in a heated shouting match with an SS officer who had been sent to keep an eye on the group. “A few of the older boys, including myself, were peeking around and saw Mr. Kraus sitting in some sort of anteroom next to this big room where we were all staying,” recalled Robert Braun. Gil, who was yelling in English at the SS officer, apparently needed the officer’s signature on a document, and the officer appeared to be in no immediate hurry to cooperate. Gil’s tolerance for bureaucratic paper shuffling had long since been exhausted. Robert and the other boys who caught sight of the altercation had never seen anything like it before. “Anytime we saw an SS officer on the street in Vienna, we’d make sure to get out of the way and try to pretend to be invisible,” said Robert. “But here Mr. Kraus was yelling at the SS officer, who was yelling back at him in German. I was frightened because I thought that the officer was going to shoot him right there.” After a few tense moments, the officer finally picked up the pen and signed the paper.

Once she had settled into her room at the Hotel Adlon, Eleanor picked up the telephone and ordered a large pot of coffee to be sent up to the room. A stiff drink might have done more to calm her nerves, but it was a little too early in the day for that; the coffee would have to suffice. After freshening up, Eleanor went back downstairs to meet Bob and walk with him to the American embassy. By this time, Ciano and von Ribbentrop had left the hotel for the signing ceremony, and the crowds that had gathered earlier in front of the Adlon had begun to disperse. The surrounding streets remained crowded, but Eleanor and Bob were able to reach the embassy without incident.

Many of the children were already there by the time they arrived. “They looked very tired,” she said. “As soon as the children saw us, some of them became very tearful. We did our best to comfort them and cheer them up.” The younger children were especially upset by the strange surroundings and were suffering from homesickness. “They all looked so weary, and most of the little ones kept crying. The more I tried to stop them, the more they seemed to cry.” Eleanor was told that Gil had already taken the first group of children upstairs to be examined by embassy officials. She grew anxious while she waited for him to appear. Finally he came downstairs and sat next to her in the hallway.

“What about the visas? What about the visas?” she asked in a trembling voice. Gil leaned close and whispered, “There are fifty visas waiting for us. All our worries are over.” Raymond Geist had lived up to his word: he had set aside all of the unused visas that they needed. None of the children would have to return to Vienna. Eleanor looked up at her husband and, for the first time in weeks, allowed herself the luxury of pure relief.

There were still bureaucratic procedures to complete. Each child needed to be interviewed and to undergo a physical examination. Many of the interviews were conducted by Cyrus Follmer, one of the American vice consuls who had been handling the visa requests that had been flooding the embassy. One child at a time was ushered into Follmer’s office and seated on a chair in front of his desk. The vice consul, aided by his German-speaking secretary, asked his questions in a gentle and patient manner. However, some of the children, exhausted and disoriented by the constant change in their surroundings, found the process distressing. The questions themselves were perfunctory—name, address, and other identifying information that, according to procedure, had to be asked directly of each child, no matter how young they were. When eight-year-old Charlotte Berg was brought in, she nervously settled herself into the chair across from Follmer, looking “like an Alice in Wonderland figure, sitting there with her long blond hair and her bright blue eyes,” wrote Eleanor.

“Can you write?” Follmer asked the quiet little girl. He smiled at her and waited for his secretary to translate his question.

“

Ja

,” she replied timidly, in German.

“Write your name here,” said Follmer as he handed her a pen and pointed to the place on the form where he wanted her to sign.

Charlotte took the pen but suddenly began to sob. Eleanor leaned in close and heard the girl mumble something but was unable to make out the words.

“What’s the matter?” Follmer asked Charlotte. “Don’t cry. Raise your head. We can’t hear you.” But the little girl, her chin down, continued to cry into her lap.

Finally, she lifted her head and managed to speak clearly enough that everyone in the office could hear. “

Muss ich Sara schreiben?

” she asked as the tears continued to stream down her face. At first, Eleanor did not understand what the girl was saying.

The name on her German passport was listed as Charlotte Sara Berg. But Sara was not her middle name. In an effort to easily identify Jews, one of Hitler’s edicts required Jewish females to list Sara as a middle name if their first names were not recognizably Jewish. Males were required to use Israel as their middle name.

Once everyone understood what the young girl was asking—“Must I write Sara?”—Follmer buried his face in his hands for a few seconds. He then looked back up at the pretty little blond-haired, blue-eyed girl sitting across from him with tears streaming down her cheeks. She was still clutching the pen in her hand.

“

Schreibe Charlotte

,” he told her, speaking as soothingly as he could. Write Charlotte. “You will always keep your name where you are going,” he said. “You will never have to write Sara again.”

It was an awesome sight to see this large ship that was going to take us to America, with the American flag flying

.

—K

URT

H

ERMAN

B

ERLIN

–H

AMBURG

–S

OUTHAMPTON

M

AY

23–25, 1939

A

fter the children completed the interviews, they returned to their dormitory, where they continued to be looked after by Hedy Neufeld and Marianne Weiss. Someone from the Hilfsverein had invited a Jewish musician to entertain the children. He arrived with a banjo and spent about an hour singing songs in Yiddish and Hebrew, which he tried to teach to the children. “It’s the only place where I ever heard a Yiddish song because I had never before heard anyone even speak Yiddish,” said Robert Braun. “In Vienna, we always spoke German, and my parents didn’t have any acquaintances who spoke Yiddish. As we were listening to these songs in Berlin, I realized that Yiddish sounded a lot like German, but not quite.”

Gil and Eleanor went back to their hotel to get some rest and then returned to check on the children early that evening, just as supper was being served. “There’s room for you here at our table. Why don’t you come and sit with us?” Henny Wenkart asked Eleanor. “Oh, that’s so nice of you, dear,” replied Eleanor. “But we already ate at our hotel.” Eleanor’s response did not sit well with the sharp-tongued Henny. “We are all traveling together, and you’re staying in a hotel while we’re staying here?” she chided Eleanor. “I guess I hadn’t become aware yet that I was now a refugee,” she recalled years later. “I was not the lawyer’s daughter from Vienna anymore.”

Early the next morning, Bob Schless took a couple of the children to a dentist after they complained about toothaches. He and Gil were determined to avoid having to leave anyone behind because of health concerns. Fortunately, the toothaches proved to be minor.

Gil and Eleanor made their way back to the American embassy, where a few remaining children still had to be interviewed. By midmorning, the last of the paperwork had been completed. They walked back to the Adlon across the Pariser Platz with the fifty visas in Gil’s briefcase. No amount of gold or diamonds could have been as valuable. Bob was waiting for them at the hotel. They quickly collected their luggage and took a taxi to the train station, where the children were already assembled. The train to Hamburg left the station right on time—a few minutes before noon. Eleanor, recalling the emotional departure from Vienna, was relieved to be leaving Berlin without another wrenching set of farewells.

“The weather was beautiful—sunny and mild,” she wrote. “The children had a very good night’s sleep. More than a dozen men and women had attended to them and had arranged our departure in a most orderly fashion.” The children had been provided with lunches to eat during the three-hour train ride to Hamburg. Gil and Eleanor walked through the train throughout the journey, changing seats often so that they could sit with different groups of children along the way.

“The attitudes of the children were interesting to us,” wrote Eleanor. “For Gil, they had lost all feeling of awe. He had become the father of them all. The little ones climbed on him and showered him with affection. The older ones clung to him and talked to him, sometimes even putting an arm about his shoulders.” As for Bob Schless, some had begun calling him Uncle Bob while others continued to address him formally as Herr Doktor. “They were witty with him, but always conscious of his revered title,” said Eleanor. “A doctor was a man to be respected, and they never forgot that.”

And Eleanor herself? “I had become the fairy godmother. If I touched one child, the others were noticeably jealous. I had to be very careful not to show special attention or affection. I was not a replacement for their own mothers.”

A pair of buses operated by the United States Lines ship company was waiting at the Hamburg train station to bring the children and adults directly to the company’s offices. To Eleanor’s chagrin, the German employees who worked for the United States Lines in Hamburg were a surly bunch. They acted put out to be helping Jewish children. “No one there was pleasant,” said Eleanor. “The red tape was endless. We missed the friendliness and help we had gotten at the embassy. There was none of that attitude here. We were kept at the office for two hours until it was time to leave to make the steamer.”

Finally, the buses brought the children and adults to the dock. Once all of the baggage had arrived from the Hamburg train station, there was yet another hurdle. Everything had to be inspected again, this time by the German customs authorities. “All of the children were lined up with their suitcases, and each one was opened for inspection,” said Eleanor. “There was a complete search of every piece of luggage. Several boys and girls were selected and chosen for a search for money.”

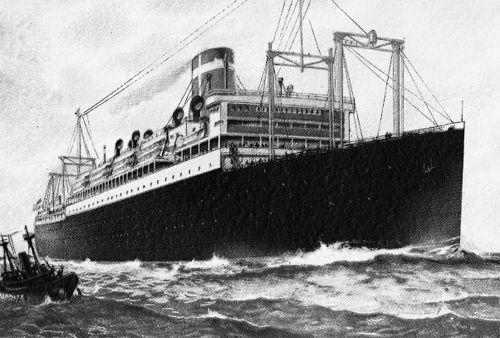

Few, if any, of the children had ever seen an ocean liner. As they waited to board, several kept staring, wide-eyed, up at the

Harding

, with its immense oil-belching smokestack and rows of lifeboats hanging off the side of the ship. “It was an awesome sight to see—this large ship that was going to take us to America, with the American flag flying,” said Kurt Herman, who had never seen a boat larger than the small barges that would occasionally float down the Danube in Vienna. “This ship was something to be remembered.”

As she waited on the dock with the children, Eleanor wanted nothing more than to board the ship. “I stared up at the gangplank,” she wrote. “I thought to myself that any minute now we would be back on American soil.”

Eleanor’s joyful anticipation was marred only by the sorrow of saying good-bye to Hedy Neufeld. She had been allowed to travel this far with the children, but Hedy was not permitted to walk along the platform that led onto the ship; the Nazi authorities were not going to risk letting someone slip away that easily. Hedy and Marianne had no choice but to stand alone behind a wire fence and watch as the children boarded the ship with the Americans. “I felt so mean pulling away from them,” said Eleanor. “We had all grown particularly close. It was a dreadful moment to see them both standing there, forlorn and dejected. It was sickening to leave her behind. I could see Hedy crying, and I could feel my own tears running down my face.”