50 Children: One Ordinary American Couple's Extraordinary Rescue Mission into the Heart of Nazi Germany (20 page)

Authors: Steven Pressman

Tags: #NF-WWII

On Friday, May 12, Gil and Eleanor woke up early and ate a hurried breakfast at the Hotel Bristol before setting out on the short walk to the Rothschild Palace on Prinz Eugenstrasse. Richard Friedmann, a thirty-year-old Jewish man Gil had met earlier at the Kultusgemeinde, was waiting for them outside the building. He had grown up in Vienna and had once worked as a journalist. Since the Anschluss, Friedmann had devoted all of his time and effort to helping Jews leave the city. By the time of Gil and Eleanor’s visit, he had already obtained passports and other exit documents for thousands of Jews. “He was delightful and charming,” wrote Eleanor. “His English was very good. All of us liked him tremendously.” Friedmann, perhaps better than any other Jew in Vienna, knew his way around the bureaucratic maze that Adolf Eichmann had set up inside the gilded Rothschild mansion.

Gil and Eleanor arrived in front of the building on Prinz Eugenstrasse at 8:45

A.M

., as Friedmann had instructed. They had a 9:00

A.M.

appointment with a Gestapo officer, and Friedmann wanted to take a few minutes to explain precisely what would happen inside. “I will take you to see the officer in charge,” he told them. “He will question you. It is better if you do not speak or appear to understand German. I will translate all of his questions and all of your answers.”

Eleanor was dazzled by the building’s immense entry hall, with its marble floors, shimmering crystal chandeliers, and a grand staircase that led to rooms upstairs that had been converted into a warren of small offices. She also noticed that some of the walls were draped in swaths of cloth that looked like bedsheets. Friedmann explained that the cloth covered valuable paintings that had belonged to the Rothschild family but had now been confiscated by the Germans, who had yet to remove them from the premises.

*

As Gil and Eleanor followed Friedmann up the marble steps, Eleanor glanced nervously at the storm troopers standing rigidly at attention at every doorway.

Upstairs Friedmann led Gil and Eleanor down a long corridor before stopping and knocking softly on a large wooden door and waiting a few moments. When they were told to enter, Eleanor stepped into the office behind Friedmann, with Gil bringing up the rear. Gil did not think to close the door behind him, which prompted an angry tirade from one of the rifle-toting guards. Gil understood just enough German to recognize the gist of the guard’s ire. “I suppose people like you have butlers in their houses who close the doors after them!” the guard shrieked at Gil before slamming the door shut and briskly striding away.

The three remained on their feet as they stood in front of the Gestapo officer, who did not get up from behind his desk. Friedmann took a step closer to the desk and waited for the officer to speak. After asking the identity of the visitors and being told they were Americans from Philadelphia, the officer shifted forward toward the edge of his chair, looking as if he was about to rise from his seat. Instead he eyed Gil and Eleanor coldly for several seconds before turning his attention back to Friedmann.

“Who are these two?” the officer demanded to know, speaking brusquely in German. As he spoke, the officer cast a dismissive glance at Gil and Eleanor.

“These are two Americans—Mr. and Mrs. Kraus from Philadelphia, in the United States,” Friedmann calmly replied. Eleanor froze at the mention of their names. Gil fought the urge to clench his fist.

The officer tilted slightly toward the edge of his chair again, as if he were preparing to stand up and finally greet his visitors. Instead he remained seated and, looking back at Friedmann, asked, “Are they Jews?”

“Yes,” Friedmann replied. “They are

American

Jews.”

Gil glanced away. He felt the muscles in his neck and back tensing up. Eleanor’s hand brushed against his ever so slightly, and he responded with a gentle and reassuring squeeze.

“Do they speak German?” the officer demanded to know.

“No, they do not,” said Friedmann.

Gil and Eleanor likely did not realize that their meeting with the Gestapo officer was essentially a scripted one. The officer, of course, knew in advance why two Jews from Philadelphia were there to see him. Richard Friedmann, who had spent countless hours in this building playing his necessary part in a cruel charade that Adolf Eichmann had engineered, equally understood that the Gestapo officer was merely playing out his own role. Rules had to be followed. Questions had to be asked. Paperwork had to be signed. And so it was that the officer turned his flinty gaze once again from Gil and Eleanor back to Friedmann, now demanding that he ask the two American Jews their purpose for coming to see him.

Friedmann turned toward Gil and Eleanor. “Why have you come to Vienna?” he asked in English. Gil looked at the young man standing next to him, and then turned toward the Gestapo officer. He answered in English, with a determined edge to his voice.

“We have come to take fifty Jewish children with us to America,” said Gil.

The officer stared closely at Gil and then looked down at a sheaf of papers that he had spread across his desk. He shuffled through the documents for a few moments, and then looked back up at his visitors. “There is no objection,” he said in a monotone, continuing to speak in German. “This couple may take these children with them. The passports will be issued.”

Friedmann motioned for Gil and Eleanor to follow him out of the office. Instinctively, Gil started to extend his arm in order to shake the officer’s hand, then quickly withdrew it. He was in Nazi Germany, not a business meeting in Philadelphia. The three visitors silently made their way back down the marble staircase, passing yet another contingent of storm troopers that had formed at the foot of the stairs in the palace’s grand foyer.

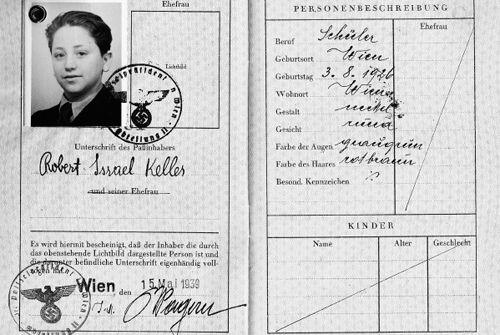

Eleanor, who could barely breathe during the meeting, wanted only to flee the building at this point. But there was still plenty of business to conduct inside the Rothschild Palace. The families had gathered in a large room on the main floor. They had been told to appear in anticipation of the decision to grant the passports, which would entail completing reams of paperwork that were required by Eichmann’s highly bureaucratic emigration process. Gil had to prove that he was authorized to take the children with him to America. In one office, he produced the documents that the parents had signed granting him guardianship of their children. In another office, he paid what amounted to a head tax for each departing child. Before leaving the building, Gil also had to provide proof that each child had a ticket for the ocean passage to America. Throughout this painstaking process, the parents and children stood still and silent as statues. There were no seats provided for them. Gil was seething inside, but he remained outwardly calm throughout the long day, determined to keep focused on the task at hand without letting his anger get the best of him. It took nearly two hours to complete all the paperwork.

Finally it was time for the parents to be questioned by the Nazi authorities, a process that would involve the approval of yet another set of documents. There was no need for the Krauses to stay at the palace, Friedmann assured them. He would remain with the families until every last bit of paperwork was completed. Gil and Eleanor made their way out of the building and walked, weary but triumphant, back to their hotel.

It would be illegal for the American consul general at Vienna to grant non-preference visas under the German quota

.

—R. C. A

LEXANDER

, U.S. S

TATE

D

EPARTMENT

B

UDAPEST

–V

IENNA

M

AY

13–17, 1939

G

il had been working nonstop, almost around the clock, from the moment he arrived in Vienna. “Gil was so overworked, so taut, so used up that we both agreed that we needed a couple of days of relaxation away from Germany,” wrote Eleanor. Bob Schless, who had visited Budapest a few weeks earlier, urged them to spend a weekend in the Hungarian capital. Budapest was the “gayest, most dazzling city in the world—far more entertaining than Paris,” he told them. That was all the encouragement they needed. Eleanor in particular was eager for a respite from Vienna’s storm troopers and Nazi banners, however brief.

As they would be gone for the entire weekend, Gil thought it would be prudent to check out of the Hotel Bristol in order to save some money. After telephoning the front desk several times, however, the bill never arrived. Gil had booked an evening train to Budapest and was running out of patience with the hotel staff, which by late afternoon still had not presented him with a bill. Finally he paid a visit to the front desk and, in no uncertain terms, demanded that the clerk hand over the bill. The clerk apologized for the delay, explaining that it had been a very busy afternoon and that the bill would soon be ready. Gil had been in Vienna long enough to realize what was happening. “The clerk had been trying to get orders from somebody as to whether or not it was all right to let us go out of the country,” wrote Eleanor. Clearly, the orders had not yet come through. Eleanor kept glancing at the large clock above the front desk. The seconds were ticking away, and she and Gil had no intention of missing their train to Budapest. “Is that clock fast?” Eleanor asked the somewhat sheepish desk clerk.

Bob came downstairs to say good-bye and could not resist having a little bit of fun. “I see there are two kinds of time in Austria,” he told the clerk, as a sly smile crossed his face. “Fast and half-assed.” Gil and Eleanor broke out in laughter. The clerk looked blankly at the three Americans; despite his command of English, he clearly did not catch the meaning of Bob’s pun. Finally, the clerk received permission to produce the hotel bill. Gil and Eleanor arrived at the train station with only minutes to spare.

They awoke the next morning in their hotel in Budapest feeling refreshed. “We felt as if we had been let out of jail,” said Eleanor. “Our room was beautiful and sunny. When the waiter brought our breakfast, he did not say ‘

Heil Hitler

.’” As she dressed for the day, Eleanor thought appreciatively of her sister Fannie, who had helped select her wardrobe during the hasty preparations for Eleanor’s journey to Europe. Uncharacteristically, Eleanor had originally thought to restrict herself to relatively plain outfits in light of the somber purpose of her journey. But Fannie convinced Eleanor that, her mission notwithstanding, she still had no good reason to dress down. Eleanor crossed the ocean with an assortment of evening dresses, along with a fox cape, strands of her favorite pearls, and a variety of other jewelry and accessories.

Walking through the city on a bright Saturday morning, Eleanor felt her spirits lifting as she and Gil drank in the colorful Hungarian sights and sounds. “It was wonderful to look into a shop window without seeing a picture of Hitler,” she wrote. “No banners, no soldiers, no parades. Just busy people going about their own affairs.” Hungary, of course, was hardly isolated from the menacing shadow that Hitler had cast across Europe in the late 1930s. By the time of Gil and Eleanor’s visit to Budapest, the country’s 450,000 Jews had already been subjected to a variety of anti-Semitic laws put into place the previous year. Similar to Germany’s anti-Jewish Nuremberg Laws, the Hungarian edicts stripped away all rights of equal citizenship that had been granted to Jews in 1867. But it would be another year before Hungary would formally align with Nazi Germany. While Gil and Eleanor were hardly naïve about Jewish persecution in Hungary and the rise of Nazi sympathies throughout the country, on this particular sunny weekend, Budapest appeared to Eleanor like a world apart from Vienna.

They dawdled over a delicious lunch at Gundel, the famed Budapest restaurant that opened in 1910 and had long been one of the city’s foremost gathering spots for artists, writers, politicians, and business leaders. Coincidentally the restaurant’s owner, Karoly Gundel, had just set up a temporary branch of his celebrated establishment on the grounds of the World’s Fair, which had opened less than two weeks earlier in New York. Following lunch, Gil and Eleanor spent the rest of the afternoon taking in the sights, strolling along the Danube, marveling at the majestic Parliament Building with its Gothic spires and soaring dome, and—for the moment at least—feeling like carefree tourists. That evening brought them to dinner at Kis Royale, yet another of Budapest’s fanciest restaurants. “I had never seen so many beautiful women in any one place in my life,” wrote Eleanor, grateful once again that she had packed appropriately for the trip. The restaurant was known for both its Hungarian paprika chicken and its lively Gypsy music, along with small statuettes of the Duke of Windsor that were placed atop each and every table. Attached to each figurine was a note reminding diners that the recently abdicated king of England had frequented the restaurant during his younger days as the Prince of Wales.