1491 (9 page)

Tisquantum’s childhood

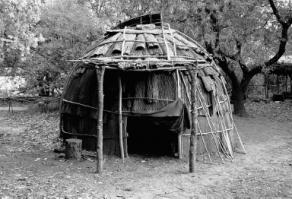

wetu

(home) was formed from arched poles lashed together into a dome that was covered in winter by tightly woven rush mats and in summer by thin sheets of chestnut bark. A fire burned constantly in the center, the smoke venting through a hole in the center of the roof. English visitors did not find this arrangement peculiar; chimneys were just coming into use in Britain, and most homes there, including those of the wealthy, were still heated by fires beneath central roof holes. Nor did the English regard the Dawnland

wetu

as primitive; its multiple layers of mats, which trapped insulating layers of air, were “warmer than our English houses,” sighed the colonist William Wood. The

wetu

was less leaky than the typical English wattle-and-daub house, too. Wood did not conceal his admiration for the way Indian mats “deny entrance to any drop of rain, though it come both fierce and long.”

Around the edge of the house were low beds, sometimes wide enough for a whole family to sprawl on them together; usually raised about a foot from the floor, platform-style; and always piled with mats and furs. Going to sleep in the firelight, young Tisquantum would have stared up at the diddering shadows of the hemp bags and bark boxes hanging from the rafters. Voices would skirl up in the darkness: one person singing a lullaby, then another person, until everyone was asleep. In the morning, when he woke, big, egg-shaped pots of corn-and-bean mash would be on the fire, simmering with meat, vegetables, or dried fish to make a slow-cooked dinner stew. Outside the

wetu

he would hear the cheerful thuds of the large mortars and pestles in which women crushed dried maize into

nokake,

a flour-like powder “so sweet, toothsome, and hearty,” colonist Gookin wrote, “that an Indian will travel many days with no other but this meal.” Although Europeans bemoaned the lack of salt in Indian cuisine, they thought it nourishing. According to one modern reconstruction, Dawnland diets at the time averaged about 2,500 calories a day, better than those usual in famine-racked Europe.

In the

wetu,

wide strips of bark are clamped between arched inner and outer poles. Because the poles are flexible, bark layers can be sandwiched in or removed at will, depending on whether the householder wants to increase insulation during the winter or let in more air during the summer. In its elegant simplicity, the

wetu’s

design would have pleased the most demanding modernist architect.

Pilgrim writers universally reported that Wampanoag families were close and loving—more so than English families, some thought. Europeans in those days tended to view children as moving straight from infancy to adulthood around the age of seven, and often thereupon sent them out to work. Indian parents, by contrast, regarded the years before puberty as a time of playful development, and kept their offspring close by until marriage. (Jarringly, to the contemporary eye, some Pilgrims interpreted this as sparing the rod.) Boys like Tisquantum explored the countryside, swam in the ponds at the south end of the harbor, and played a kind of soccer with a small leather ball; in the summer and fall they camped out in huts in the fields, weeding the maize and chasing away birds. Archery practice began at age two. By adolescence boys would make a game of shooting at each other and dodging the arrows.

The primary goal of Dawnland education was molding character. Men and women were expected to be brave, hardy, honest, and uncomplaining. Chatterboxes and gossips were frowned upon. “He that speaks seldom and opportunely, being as good as his word, is the only man they love,” Wood explained. Character formation began early, with family games of tossing naked children into the snow. (They were pulled out quickly and placed next to the fire, in a practice reminiscent of Scandinavian saunas.) When Indian boys came of age, they spent an entire winter alone in the forest, equipped only with a bow, a hatchet, and a knife. These methods worked, the awed Wood reported. “Beat them, whip them, pinch them, punch them, if [the Indians] resolve not to flinch for it, they will not.”

Tisquantum’s regimen was probably tougher than that of his friends, according to Salisbury, the Smith College historian, for it seems that he was selected to become a

pniese,

a kind of counselor-bodyguard to the sachem. To master the art of ignoring pain, future

pniese

had to subject themselves to such miserable experiences as running barelegged through brambles. And they fasted often, to learn self-discipline. After spending their winter in the woods,

pniese

candidates came back to an additional test: drinking bitter gentian juice until they vomited, repeating this bulimic process over and over until, near fainting, they threw up blood.

Patuxet, like its neighboring settlements, was governed by a sachem, who upheld the law, negotiated treaties, controlled foreign contacts, collected tribute, declared war, provided for widows and orphans, and allocated farmland when there were disputes over it. (Dawnlanders lived in a loose scatter, but they knew which family could use which land—“very exact and punctuall,” Roger Williams, founder of Rhode Island colony, called Indian care for property lines.) Most of the time, the Patuxet sachem owed fealty to the great sachem in the Wampanoag village to the southwest, and through him to the sachems of the allied confederations of the Nauset in Cape Cod and the Massachusett around Boston. Meanwhile, the Wampanoag were rivals and enemies of the Narragansett and Pequots to the west and the many groups of Abenaki to the north. As a practical matter, sachems had to gain the consent of their people, who could easily move away and join another sachemship. Analogously, the great sachems had to please or bully the lesser, lest by the defection of small communities they lose stature.

Sixteenth-century New England housed 100,000 people or more, a figure that was slowly increasing. Most of those people lived in shoreline communities, where rising numbers were beginning to change agriculture from an option to a necessity. These bigger settlements required more centralized administration; natural resources like good land and spawning streams, though not scarce, now needed to be managed. In consequence, boundaries between groups were becoming more formal. Sachems, given more power and more to defend, pushed against each other harder. Political tensions were constant. Coastal and riverine New England, according to the archaeologist and ethnohistorian Peter Thomas, was “an ever-changing collage of personalities, alliances, plots, raids and encounters which involved every Indian [settlement].”

Armed conflict was frequent but brief and mild by European standards. The

casus belli

was usually the desire to avenge an insult or gain status, not the wish for conquest. Most battles consisted of lightning guerrilla raids by ad hoc companies in the forest: flash of black-and-yellow-striped bows behind trees, hiss and whip of stone-tipped arrows through the air, eruption of angry cries. Attackers slipped away as soon as retribution had been exacted. Losers quickly conceded their loss of status. Doing otherwise would have been like failing to resign after losing a major piece in a chess tournament—a social irritant, a waste of time and resources. Women and children were rarely killed, though they were sometimes abducted and forced to join the winning group. Captured men were often tortured (they were admired, though not necessarily spared, if they endured the pain stoically). Now and then, as a sign of victory, slain foes were scalped, much as British skirmishes with the Irish sometimes finished with a parade of Irish heads on pikes. In especially large clashes, adversaries might meet in the open, as in European battlefields, though the results, Roger Williams noted, were “farre less bloudy, and devouring then the cruell Warres of Europe.” Nevertheless, by Tisquantum’s time defensive palisades were increasingly common, especially in the river valleys.

Inside the settlement was a world of warmth, family, and familiar custom. But the world outside, as Thomas put it, was “a maze of confusing actions and individuals fighting to maintain an existence in the shadow of change.”

And that was before the Europeans showed up.

TOURISM AND TREACHERY

British fishing vessels may have reached Newfoundland as early as the 1480s and areas to the south soon after. In 1501, just nine years after Columbus’s first voyage, the Portuguese adventurer Gaspar Corte-Real abducted fifty-odd Indians from Maine. Examining the captives, Corte-Real found to his astonishment that two were wearing items from Venice: a broken sword and two silver rings. As James Axtell has noted, Corte-Real probably was able to kidnap such a large number of people only because the Indians were already so comfortable dealing with Europeans that big groups willingly came aboard his ship.

*4

The earliest written description of the People of the First Light was by Giovanni da Verrazzano, an Italian mariner-for-hire commissioned by the king of France in 1523 to discover whether one could reach Asia by rounding the Americas to the north. Sailing north from the Carolinas, he observed that the coastline everywhere was “densely populated,” smoky with Indian bonfires; he could sometimes smell the burning hundreds of miles away. The ship anchored in wide Narragansett Bay, near what is now Providence, Rhode Island. Verrazzano was one of the first Europeans the natives had seen, perhaps even the first, but the Narragansett were not intimidated. Almost instantly, twenty long canoes surrounded the visitors. Cocksure and graceful, the Narragansett sachem leapt aboard: a tall, longhaired man of about forty with multicolored jewelry dangling about his neck and ears, “as beautiful of stature and build as I can possibly describe,” Verrazzano wrote.

His reaction was common. Time and time again Europeans described the People of the First Light as strikingly healthy specimens. Eating an incredibly nutritious diet, working hard but not broken by toil, the people of New England were taller and more robust than those who wanted to move in—“as proper men and women for feature and limbes as can be founde,” in the words of the rebellious Pilgrim Thomas Morton. Because famine and epidemic disease had been rare in the Dawnland, its inhabitants had none of the pox scars or rickety limbs common on the other side of the Atlantic. Native New Englanders, in William Wood’s view, were “more amiable to behold (though [dressed] only in Adam’s finery) than many a compounded fantastic [English dandy] in the newest fashion.”

The Pilgrims were less sanguine about Indians’ multicolored, multitextured mode of self-presentation. To be sure, the newcomers accepted the practicality of deerskin robes as opposed to, say, fitted British suits. And the colonists understood why natives’ skin and hair shone with bear or eagle fat (it warded off sun, wind, and insects). And they could overlook the Indians’ practice of letting prepubescent children run about without a stitch on. But the Pilgrims, who regarded personal adornment as a species of idolatry, were dismayed by what they saw as the indigenous penchant for foppery. The robes were adorned with animal-head mantles, snakeskin belts, and bird-wing headdresses. Worse, many Dawnlanders tattooed their faces, arms, and legs with elaborate geometric patterns and totemic animal symbols. They wore jewelry made of shell and swans’-down earrings and chignons spiked with eagle feathers. If that weren’t enough, both sexes painted their faces red, white, and black—ending up, Gookin sniffed, with “one part of their face of one color; and another, of another, very deformedly.”

In 1585–86 the artist John White spent fifteen months in what is now North Carolina, returning with more than seventy watercolors of American people, plants, and animals. White’s work, later distributed in a series of romanticized engravings (two of which are shown here), was not of documentary quality by today’s standards—his Indians are posed like Greek statues. But at the same time his intent was clear. To his eye, the people of the Carolinas, cultural cousins to the Wampanoag, were in superb health, especially compared to poorly nourished, smallpox-scarred Europeans. And they lived in what White viewed as well-ordered settlements, with big, flourishing fields of maize.