1491 (10 page)

And the

hair!

As a rule, young men wore it long on one side, in an equine mane, but cropped the other side short, which prevented it from getting tangled in their bow strings. But sometimes they cut their hair into such wild patterns that attempting to imitate them, Wood sniffed, “would torture the wits of a curious barber.” Tonsures, pigtails, head completely shaved but for a single forelock, long sides drawn into a queue with a raffish short-cut roach in the middle—all of it was prideful and abhorrent to the Pilgrims. (Not everyone in England saw it that way. Inspired by asymmetrical Indian coiffures, seventeenth-century London blades wore long, loose hanks of hair known as “lovelocks.”)

As for the Indians, evidence suggests that they tended to view Europeans with disdain as soon as they got to know them. The Wendat (Huron) in Ontario, a chagrined missionary reported, thought the French possessed “little intelligence in comparison to themselves.” Europeans, Indians told other Indians, were physically weak, sexually untrustworthy, atrociously ugly, and just plain smelly. (The British and French, many of whom had not taken a bath in their entire lives, were amazed by the Indian interest in personal cleanliness.) A Jesuit reported that the “savages” were disgusted by handkerchiefs: “They say, we place what is unclean in a fine white piece of linen, and put it away in our pockets as something very precious, while they throw it upon the ground.” The Mi’kmaq in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia scoffed at the notion of European superiority. If Christian civilization was so wonderful, why were its inhabitants all trying to settle somewhere else?

For fifteen days Verrazzano and his crew were the Narragansett’s honored guests—though the Indians, Verrazzano admitted, kept their women out of sight after hearing the sailors’ “irksome clamor” when females came into view. Much of the time was spent in friendly barter. To the Europeans’ confusion, their steel and cloth did not interest the Narragansett, who wanted to swap only for “little bells, blue crystals, and other trinkets to put in the ear or around the neck.” On Verrazzano’s next stop, the Maine coast, the Abenaki

did

want steel and cloth—demanded them, in fact. But up north the friendly welcome had vanished. The Indians denied the visitors permission to land; refusing even to touch the Europeans, they passed goods back and forth on a rope over the water. As soon as the crew members sent over the last items, the locals began “showing their buttocks and laughing.” Mooned by the Indians! Verrazzano was baffled by this “barbarous” behavior, but the reason for it seems clear: unlike the Narragansett, the Abenaki had long experience with Europeans.

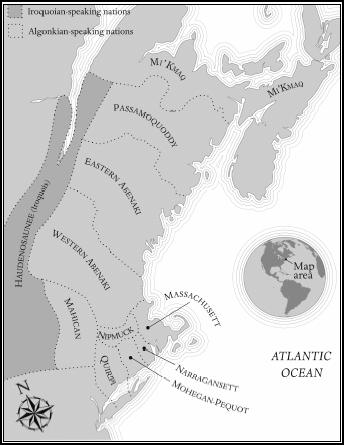

PEOPLES OF THE DAWNLAND, 1600 A.D.

During the century after Verrazzano Europeans were regular visitors to the Dawnland, usually fishing, sometimes trading, occasionally kidnapping natives as souvenirs. (Verrazzano had grabbed one himself, a boy of about eight.) By 1610 Britain alone had about two hundred vessels operating off Newfoundland and New England; hundreds more came from France, Spain, Portugal, and Italy. With striking uniformity, these travelers reported that New England was thickly settled and well defended. In 1605 and 1606 Samuel de Champlain, the famous explorer, visited Cape Cod, hoping to establish a French base. He abandoned the idea. Too many people already lived there. A year later Sir Ferdinando Gorges—British, despite the name—tried to found a community in Maine. It began with more people than the Pilgrims’ later venture in Plymouth and was better organized and supplied. Nonetheless, the local Indians, numerous and well armed, killed eleven colonists and drove the rest back home within months.

Many ships anchored off Patuxet. Martin Pring, a British trader, camped there with a crew of forty-four for seven weeks in the summer of 1603, gathering sassafras—the species was common in the cleared, burned-over areas at the edge of Indian settlements. To ingratiate themselves with their hosts, Pring’s crew regularly played the guitar for them (the Indians had drums, flutes, and rattles, but no string instruments). Despite the entertainment, the Patuxet eventually got tired of the foreigners camping out on their land. Giving their guests a subtle hint that they should be moving on, 140 armed locals surrounded their encampment. Next day the Patuxet burned down the woodlands where Pring and his men were working. The foreigners left within hours. Some two hundred Indians watched them from the shore, politely inviting them to come back for another short visit. Later Champlain, too, stopped at Patuxet, but left before wearing out his welcome.

Tisquantum probably saw Pring, Champlain, and other European visitors, but the first time Europeans are known to have affected his life was in the summer of 1614. A small ship hove to, sails a-flap. Out to meet the crew came the Patuxet. Almost certainly the sachem would have been of the party; he would have been accompanied by his

pniese,

including Tisquantum. The strangers’ leader was a sight beyond belief: a stocky man, even shorter than most foreigners, with a voluminous red beard that covered so much of his face that he looked to Indian eyes more beast than human. This was Captain John Smith of Pocahontas fame. According to Smith, he had lived an adventurous and glamorous life. As a youth, he claimed, he had served as a privateer, after which he was captured and enslaved by the Turks. He escaped and awarded himself the rank of captain in the army of Smith.

*5

Later he actually became captain of a ship and traveled to North America several times. On this occasion he had sailed to Maine with two ships, intending to hunt whales. The party spent two months chasing the beasts but failed to catch a single one. Plan B, Smith wrote later, was “Fish and Furs.” He assigned most of the crew to catch and dry fish in one ship while he puttered up and down the coast with the other, bartering for furs. In the middle of this perambulating he showed up in Patuxet.

Despite Smith’s peculiar appearance, Tisquantum and his fellows treated him well. They apparently gave him a tour, during which he admired the gardens, orchards, and maize fields, and the “great troupes of well-proportioned people” tending them. At some point a quarrel occurred and bows were drawn, Smith said, “fortie or fiftie” Patuxet surrounding him. His account is vague, but one imagines that the Indians were hinting at a limit to his stay. In any case, the visit ended cordially enough, and Smith returned to Maine and then England. He had a map drawn of what he had seen, persuaded Prince Charles to look at it, and curried favor with him by asking him to award British names to all the Indian settlements. Then he put the maps in the books he wrote to extol his adventures. In this way Patuxet acquired its English name, Plymouth, after the city in England (it was then spelled “Plimoth”).

Smith left his lieutenant, Thomas Hunt, behind in Maine to finish loading the other ship with dried fish. Without consulting Smith, Hunt decided to visit Patuxet. Taking advantage of the Indians’ recent good experience with English visitors, he invited people to come aboard. The thought of a summer day on the foreigners’ vessel must have been tempting. Several dozen villagers, Tisquantum among them, canoed to the ship. Without warning or pretext the sailors tried to shove them into the hold. The Indians fought back. Hunt’s men swept the deck with small-arms fire, creating “a great slaughter.” At gunpoint, Hunt forced the survivors belowdecks. With Tisquantum and at least nineteen others, he sailed to Europe, stopping only once, at Cape Cod, where he kidnapped seven Nauset.

In Hunt’s wake the Patuxet community raged, as did the rest of the Wampanoag confederacy and the Nauset. The sachems vowed not to let foreigners rest on their shores again. Because of the “worthlesse” Hunt, lamented Gorges, the would-be colonizer of Maine, “a warre [was] now new begunne between the inhabitants of those parts, and us.” Despite European guns, the Indians’ greater numbers, entrenched positions, knowledge of the terrain, and superb archery made them formidable adversaries. About two years after Hunt’s offenses, a French ship wrecked at the tip of Cape Cod. Its crew built a rude shelter with a defensive wall made from poles. The Nauset, hidden outside, picked off the sailors one by one until only five were left. They captured the five and sent them to groups victimized by European kidnappers. Another French vessel anchored in Boston Harbor at about the same time. The Massachusett killed everyone aboard and set the ship afire.

Tisquantum was away five years. When he returned, everything had changed—calamitously. Patuxet had vanished. The Pilgrims had literally built their village on top of it.

THE PLACE OF THE SKULL

According to family lore, my great-grandmother’s great-grandmother’s great-grandfather was the first white person hanged in North America. His name was John Billington. He emigrated aboard the

Mayflower,

which anchored off the coast of Massachusetts on November 9, 1620. Billington was not among the company of saints, to put it mildly; within six months of arrival he became the first white person in America to be tried for sassing the police. His two sons were no better. Even before landing, one nearly blew up the

Mayflower

by shooting a gun at a keg of gunpowder while inside the ship. After the Pilgrims landed the other son ran off to live with some nearby Indians, leading to great consternation and an expedition to fetch him back. Meanwhile Billington père made merry with other non-Puritan lowlifes and haphazardly plotted against authority. The family was “one of the profanest” in Plymouth colony, complained William Bradford, its long-serving governor. Billington, in his opinion, was “a knave, and so shall live and die.” What one historian called Billington’s “troublesome career” ended in 1630 when he was hanged for shooting somebody in a quarrel. My family has always claimed that he was framed—but we

would

say that, wouldn’t we?

Growing up, I was always tickled by this raffish personal connection to history: part of the Puritans, but not actually puritanical. As an adult, I decided to learn more about Billington. A few hours at the library sufficed to convince me that some aspects of our agreeable family legend were untrue. Although Billington was in fact hanged, at least two other Europeans were executed in North America before him. And one of them was convicted for the much more interesting offense of killing his pregnant wife and eating her. My ancestor was probably only No. 3, and there is a whisper of scholarly doubt about whether he deserves to be even that high on the list.

I had learned about Plymouth in school. But it was not until I was poking through the scattered references to Billington that it occurred to me that my ancestor, like everyone else in the colony, had voluntarily enlisted in a venture that had him arriving in New England without food or shelter six weeks before winter. Not only that, he joined a group that, so far as is known, set off with little idea of where it was heading. In Europe, the Pilgrims had refused to hire the experienced John Smith as a guide, on the theory that they could use the maps in his book. In consequence, as Smith later crowed, the hapless

Mayflower

spent several frigid weeks scouting around Cape Cod for a good place to land, during which time many colonists became sick and died. Landfall at Patuxet did not end their problems. The colonists had intended to produce their own food, but inexplicably neglected to bring any cows, sheep, mules, or horses. To be sure, the Pilgrims had intended to make most of their livelihood not by farming but by catching fish for export to Britain. But the only fishing gear the Pilgrims brought was useless in New England. Half of the 102 people on the

Mayflower

made it through the first winter, which to me seemed amazing. How did they survive?

In his history of Plymouth colony, Governor Bradford himself provides one answer: robbing Indian houses and graves. The

Mayflower

hove to first at Cape Cod. An armed company of Pilgrims staggered out. Eventually they found a deserted Indian habitation. The newcomers—hungry, cold, sick—dug open burial sites and ransacked homes, looking for underground stashes of food. After two days of nervous work the company hauled ten bushels of maize back to the

Mayflower,

carrying much of the booty in a big metal kettle the men had also stolen. “And sure it was God’s good providence that we found this corn,” Winslow wrote, “for else we know not how we should have done.”

The Pilgrims were typical in their lack of preparation. Expeditions from France and Spain were usually backed by the state, and generally staffed by soldiers accustomed to hard living. English voyages, by contrast, were almost always funded by venture capitalists who hoped for a quick cash-out. Like Silicon Valley in the heyday of the Internet bubble, London was the center of a speculative mania about the Americas. As with the dot-com boom, a great deal of profoundly fractured cerebration occurred. Decades after first touching the Americas, London’s venture capitalists still hadn’t figured out that New England is colder than Britain despite being farther south. Even when they focused on a warmer place like Virginia, they persistently selected as colonists people ignorant of farming; multiplying the difficulties, the would-be colonizers were arriving in the middle of a severe, multiyear drought. As a result, Jamestown and the other Virginia forays survived on Indian charity—they were “utterly dependent and therefore controllable,” in the phrase of Karen Ordahl Kuppermann, a New York University historian. The same held true for my ancestor’s crew in Plymouth.