13 Bankers: The Wall Street Takeover and the Next Financial Meltdown (12 page)

Read 13 Bankers: The Wall Street Takeover and the Next Financial Meltdown Online

Authors: Simon Johnson

At the time, nonfinancial corporations had relatively simple financial needs, at least compared to the plethora of products and services available today: they raised short-term money by taking out bank loans, they raised long-term money by issuing bonds, and they raised capital by issuing stock. The loans were extended and held by commercial banks; the bonds and stocks were placed by investment banks with investors for a small slice of the proceeds. Since investment banks were not making loans directly, holding large chunks of corporate debt or equity, or trading large volumes of securities on their own account, there was little need for massive investment banks; from 1946 through 1981, total financial assets of all securities broker-dealers remained under 2 percent of U.S. GDP.

26

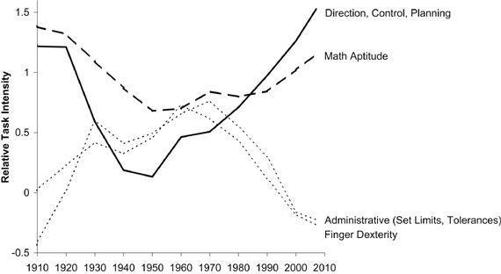

“Boring banking” was reflected in the nature of the work done in the financial industry, which would be largely unrecognizable to people accustomed to today’s era of quantitative sophistication and perpetual innovation. Thomas Philippon and Ariell Reshef have analyzed the task complexity of the jobs done by employees in financial services firms over the last century (

Figure 3-2

) and found that math aptitude and decision-making were less important between 1940 and 1970 than either earlier or later in the century. By contrast, finger dexterity and routine administrative tasks were relatively more important during this period than in the earlier or later periods.

27

This does not mean that bankers somehow became noncompetitive and lost the urge to make money after the Depression. There were plenty of attempts to skirt existing banking regulations. Large bank holding companies evaded restrictions on interstate banking by buying separate subsidiary banks in multiple states; thrifts—savings banks and savings and loan associations founded to serve households—competed for deposits by offering interest rates above what commercial banks could pay. But during this period, the federal government took active steps to close regulatory loopholes and maintain the basic framework created in the 1930s. The Bank Holding Company Act of 1956 increased regulation of bank holding companies and limited their ability to buy banks in multiple states. In 1966, Congress gave the Federal Reserve authority to regulate deposit rates paid by thrifts. Congress even expanded the regulatory framework to include stronger consumer protection measures, such as the Truth in Lending Act of 1968 and the Fair Credit Reporting Act of 1970. Not only was the government making sure that banks were safe and sound, it was trying to make sure that banks did not abuse their customers.

28

Figure 3-2: Realtive Job Complexity in the Financial Sector

Source: Thomas Philippon and Ariell Reshef, “Wages and Human Capital in the U.S. Financial Industry: 1909–2006,” Figure 3.

During most of this period, the American economy flourished. From 1947 to 1973, real GDP (adjusted for inflation) grew at an average annual growth rate of 4.0 percent,

29

and American corporations grew, prospered, and expanded throughout the world. This was a period of major technological innovation in multiple capital-intensive industries, as the middle class bought cars and household appliances, the government spent heavily on an increasingly sophisticated defense industry, and the revolution in computer technology began with the development of mainframes and minicomputers. It also saw the emergence of the modern venture capital industry, which has played a crucial role in the funding of technological innovation. There were many reasons for the success of the postwar economy, but it is clear that “boring banking” did not constrain financing of innovation and development. Instead, it facilitated a phase of tremendous growth in economic output and prosperity.

CHANGING BANKING

Beginning in the 1970s and accelerating through the 1980s, the financial services industry broke free from the constraints of the Depression-era bargain. While there were banking executives who hoped for wholesale deregulation, there was no concerted plan by the financial sector to overthrow its regulatory constraints. Instead, like many historical phenomena, this development emerged from a confluence of factors: exogenous events, such as the high inflation of the 1970s; the emergence of academic finance; and the broader deregulatory trend begun in the administration of Jimmy Carter but transformed into a crusade by Ronald Reagan. The eventual result was an out-of-balance financial system that still enjoyed the backing of the federal government—what president would allow the financial system to collapse on his watch?—without the regulatory oversight necessary to prevent excessive risk-taking.

Like many major trends, this one was not entirely visible to its participants at the outset. Throughout American history, regulatory change has been more about settling disputes between segments of the business community than about sweeping social transformations, and the beginnings of financial deregulation were no different.

Fixed commissions for stock trading were one of the first dominoes to fall. As David Komansky, later CEO of Merrill Lynch, recalled, “There was no discounting, no negotiating. Fixed prices meant fixed prices for the entire Street; we couldn’t give you a discount even if we wanted to. It was the greatest thing in the world.”

30

Most Wall Street brokerage firms were happy to profit from this cartel. But not everyone saw things this way. Large institutional investors such as mutual funds and pension funds, which had grown in importance as increasingly affluent Americans amassed savings and large corporations set up pension plans for their employees, wanted lower prices for their large orders. Donald Regan, CEO of Merrill Lynch in the early 1970s, also wanted an end to fixed commissions. Merrill, as the largest broker on Wall Street, stood to gain the most from competition, and Regan already had a vision of his company as a large, diversified financial services firm.

31

William Salomon, then head of Salomon Brothers, also supported an end to fixed commissions.

32

Called upon to adjudicate this dispute in the early 1970s, the Securities and Exchange Commission obliged, ordering the elimination of fixed commissions in the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE).

33

The NYSE complied on May 1, 1975, which had ripple effects through-out the securities industry. Competition over brokerage commissions meant that institutional investors could make large trades much more cheaply, leading to an increase in trading volume. After enjoying comfortable, cartel-like profits for decades, securities brokers were now given a much larger market, but also a much more competitive one. One source of competition was brokers such as Charles Schwab who focused on providing discounted services to individuals. As a result, the small partnerships that had populated Wall Street for decades began to fade away, replaced by larger, more heavily capitalized firms that expanded into higher-margin businesses, searching for new sources of profits.

34

The world of traditional commercial and savings banks was also undergoing changes that would have far-reaching implications. One precipitating factor was the high inflation of the 1970s. High inflation meant higher interest rates, since no one will lend money at 3 percent if inflation is 6 percent. Because the interest paid on traditional savings accounts was capped by Regulation Q, money flowed out of those accounts toward higher-yielding Treasury bills and other forms of short-term debt issued by corporations and governments.

*

Money market funds,

†

invented in 1971, grew from only $3 billion in assets in 1976 to $230 billion by 1982.

35

At the same time as banks were losing their easy source of cheap funds, rising interest rates meant that they were losing money on the mortgages they had made, mostly at fixed rates. Many mortgages made in the early 1970s

36

were still paying only 7 percent even as inflation spiked into double digits at the end of the decade, meaning banks were not even receiving enough interest to make up for inflation. (Homeowners, on the other hand, profited as their debts were inflated away—helping to convince a generation of Americans that houses were the best investment they could possibly make.)

These economic shifts primarily affected savings and loan associations (S&Ls), which were more exposed to mortgages than commercial banks. But at the time, the S&Ls—not the Wall Street investment banks—and their lobbying organization, the United States League of Savings Institutions, were a powerful political force with influence on both sides of the political aisle. Although individually small, they had a favorable public image (in a country that professes to live by small-town values), they were located in virtually every congressional district, and they benefited from the disproportionate representation of rural states in the Senate. “When it came to thrift matters in Congress, the U.S. League and many of its affiliates were the de facto government,” said former Federal Home Loan Bank head Edwin J. Gray in 1989.

37

In response to S&L pressure, Congress passed the Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980, which phased out Regulation Q, enabling banks to compete for deposits by paying higher interest rates—in the process eliminating one pillar of the “boring banking” business model. No longer able to rely on an artificially low cost of money, banks would have to seek new sources of revenue in new businesses. The bill eased this shift by allowing S&Ls to expand from home mortgages into a range of riskier loans and investments, making it easier for them to make the mistakes that produced the S&L crisis later in the decade. The bill also overrode any state laws restricting the interest that could be charged on first mortgages—meaning that banks could charge whatever interest rates the market would bear.

38

By 1980, the traditional business models of both investment and commercial banking were eroding in the face of macroeconomic changes and the first waves of deregulation. As historian Charles Geisst wrote of Wall Street, “A turning point had been reached on the Street.… The more placid days of the past were gone forever.”

39

There was still no coherent program or ideology that laid out what the financial services industry should look like and what its relationship to the government should be. But that was changing.

At the time, a movement was growing in the halls of America’s leading universities that would help transform the financial sector. This movement was the discipline of academic finance, pioneered by economists such as Paul Samuelson, Franco Modigliani, Merton Miller, Harry Markowitz, William Sharpe, Eugene Fama, Fischer Black, Robert Merton, and Myron Scholes, most of whom went on to win the Nobel Prize. These scholars brought sophisticated mathematics to bear on such problems as determining the optimal capital structure of a firm (the ratio between debt and equity), pricing financial assets, and separating and hedging risks.

40

Academic finance had a tremendous impact on the way business is done around the globe. For example, research on capital structure contributed to a significant increase in indebtedness by corporations.

41

(Debt provides leverage, and therefore increases expected returns along with risk.) It also expanded the market for advising corporations on their funding strategies—a lucrative opportunity investment bankers quickly seized. Similarly, the quantitative study of financial markets helped bankers identify a new universe of ways to make money. New methods for calculating the relative value of financial assets made possible arbitrage trading, where traders sought out small pricing discrepancies that, in theory, should not exist; by betting that the market would make these discrepancies disappear, they could make almost certain money. The Black-Scholes Model (developed by Black, Scholes, and Merton) provided a handy formula for calculating the price of a financial derivative, and in the process gave rise to the derivatives revolution.

Thus academic finance produced important tools that would create new markets and vast new sources of revenues for Wall Street. But it was perhaps even more important for the ideology it created. A central assertion of the academic finance movement in the 1960s and 1970s became known as the Efficient Market Hypothesis: precisely because traders are looking for and exploiting inefficiencies in asset prices, those inefficiencies cannot last for more than a brief period of time; as a result, prices are always “right.” As outlined by Eugene Fama in 1970, the Efficient Market Hypothesis comes in a weak form, a semi-strong form, and a strong form. The weak form holds that future prices cannot be predicted from past prices; the semi-strong form holds that prices adjust quickly to all publicly available information (meaning that by the time you read the news in the newspaper, it is too late to make money on the news); and the strong form holds that

no one

has any information that can be used to predict future prices, so market prices are always right. At the time, Fama argued, with empirical evidence, that the weak and semi-strong forms were correct. He acknowledged that there are exceptions to the strong form—exchange floor traders and corporate insiders do have information they can profit from—but found no evidence that anyone else (mutual fund managers, for example) is able to “beat the market” through better information or analysis.

42