13 Bankers: The Wall Street Takeover and the Next Financial Meltdown (11 page)

Read 13 Bankers: The Wall Street Takeover and the Next Financial Meltdown Online

Authors: Simon Johnson

What had happened?

*

Standard & Poor’s and other credit rating agencies rate bonds issued by governments and companies. The ratings are supposed to reflect the likelihood that the issuer will pay off its debts. A rating downgrade indicates that the agency is losing confidence in the issuer.

*

There was one huge difference, which was that money did not leave the country; instead, it left the private sector for the safety of U.S. Treasury obligations. But the effect on the private sector financial system was the same.

3

WALL STREET RISING

1980–

In this present crisis, government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.

—Ronald Reagan, inaugural address, January 20, 1981

1

On December 9, 1985, the cover of

Business Week

featured John Gutfreund, the CEO of Salomon Brothers and “The King of Wall Street.” “Merrill Lynch remains the best-known Wall Street house and Goldman Sachs the best-managed, but Salomon Bros. is the firm most feared by its competitors,” wrote Anthony Bianco. “It is the prototype of the thoroughly modern investment bank—the not-so-benevolent King of the Street.”

2

Salomon was the epitome of the new breed of Wall Street investment bank, built around a swashbuckling, risk-taking bond trading operation powered by “quants” recruited from academic research institutions and filled with “financial engineers” designing new products. Its strategy was to take large risks on its own account rather than simply taking fees for providing advice or executing trades. As Bianco put it, “What sets Salomon apart is the sheer scale on which it oper-ates in the markets, reflecting an appetite for risk unrivaled among financial middlemen.” Four years later,

Liar’s Poker,

Michael Lewis’s memoir of his years at Salomon, would cement its status as the paradigmatic bank of the 1980s, the same decade that produced the original Oliver Stone

Wall Street

movie, with Gordon Gekko’s famous “Greed is good” speech.

Looking back, however, Salomon seems so … small. When the

Business Week

story was written, it had $68 billion in assets and $2.8 billion in shareholders’ equity. It expected to earn $1.1 billion in operating profits for all of 1985. The next year, Gutfreund earned $3.2 million.

3

At the time, those numbers seemed extravagant. Today? Not so much.

If the financial crisis of 2007–2009 produced a king of Wall Street, it would most likely be Jamie Dimon, CEO of JPMorgan Chase and the “Last Man Standing,” according to the title of a recent book.

4

(Lloyd Blankfein of Goldman Sachs would be the other contender.) Compared to other megabanks, JPMorgan was less exposed to toxic securities and came through the credit crisis in better shape. In addition, it capitalized on the problems of other banks to snap up Bear Stearns and Washington Mutual, gaining strength in both investment banking and retail banking. And it took advantage of its weakened competitors to grab market share across the board, taking the top spot in investment banking revenues in the first half of 2009.

5

At his company’s annual meeting in May 2009, Dimon could justifiably claim, “This might have been our finest year ever.”

6

In addition, his status as a longtime Democratic donor with strong political connections, as well as the Obama administration’s need to work with someone on Wall Street, gave him increased influence in Washington. Dimon,

The New York Times

wrote in July 2009, “has emerged as President Obama’s favorite banker, and in turn, the envy of his Wall Street rivals.”

7

At the time, JPMorgan Chase had over $2 trillion in assets,

8

not counting positions not recorded on its balance sheet, such as derivatives exposures; it had $155 billion in balance sheet equity; and it earned $4.1 billion in operating profits in the second quarter alone. By comparison, the 1985 Salomon Brothers, even after converting to 2009 dollars to account for inflation, only had $122 billion in assets, $5 billion in equity, and $2 billion in operating profits for an entire year.

9

(Goldman Sachs, as a pure investment bank, offered perhaps a more accurate comparison to Salomon; in the second quarter of 2009, it had $890 billion in assets, $63 billion in equity, and $5 billion in operating profits.)

10

Although Dimon voluntarily took no cash bonus for 2008, his total compensation including stock awards was still $19.7 million, more than three times Gutfreund’s inflation-adjusted earnings of $5.8 million.

11

And this was in a bad year for Wall Street CEOs; in 2007, Dimon earned $34 million, Blankfein $54 million, John Thain of Merrill Lynch $84 million, and John Mack of Morgan Stanley $41 million.

12

Something changed during the last quarter-century. One factor was a wave of mergers that created fewer and fewer, but larger and larger, financial institutions. JPMorgan Chase was the product of the mergers of Chemical Bank, Manufacturers Hanover, Chase Manhattan, J.P. Morgan, Bank One, and First Chicago—all since 1991—even before the bargain-basement acquisitions of Bear Stearns and Washington Mutual in 2008. (Salomon itself was acquired by Travelers, which then merged with Citicorp into Citigroup.)

In addition, the financial sector itself simply got bigger and bigger. When John Gutfreund became CEO of Salomon in 1978, all commercial banks together held $1.2 trillion of assets, equivalent to 53 percent of U.S. GDP. By the end of 2007, the commercial banking sector had grown to $11.8 trillion in assets, or 84 percent of U.S. GDP. But that was only a small part of the story. Securities broker-dealers (investment banks), including Salomon, grew from $33 billion in assets, or 1.4 percent of GDP, to $3.1 trillion in assets, or 22 percent of GDP. Asset-backed securities such as collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), which hardly existed in 1978, accounted for another $4.5 trillion in assets in 2007, or 32 percent of GDP.

*

All told, the debt held by the financial sector grew from $2.9 trillion, or 125 percent of GDP, in 1978 to over $36 trillion, or 259 percent of GDP, in 2007.

13

Some of this growth was due to an increase in borrowing by the nonfinancial sector—the “real economy.” However, the expansion of the financial sector vastly outpaced growth in households and nonfinancial companies. Instead, most of the growth in the financial sector was due to the increasing “financialization” of the economy—the transformation of one dollar of lending to the real economy into many dollars of financial transactions. In 1978, the financial sector borrowed $13 in the credit markets for every $100 borrowed by the real economy; by 2007, that had grown to $51.

14

In other words, for the same amount of borrowing by households and nonfinancial companies, the amount of borrowing by financial institutions quadrupled.

Even these numbers do not include the derivatives positions that financial institutions were building up at the same time, because derivatives—bets on the value of other assets, such as stocks or currencies—are not conventionally accounted for on bank balance sheets. Worldwide, over-the-counter derivatives, which essentially did not exist in 1978, grew to over $33 trillion in market value—over twice U.S. GDP—by the end of 2008.

15

A large portion of these derivatives was held by U.S. financial institutions, which were among the world leaders in the business. No matter how you measure it, the size and economic influence of America’s financial sector grew enormously over the past thirty years; the Salomon Brothers of 1985 would be trivial today.

As the financial sector amassed more and more assets, it became a bigger part of the national economy. Between 1978 and 2007, the financial sector grew from 3.5 percent to 5.9 percent of the economy (measured by contribution to GDP).

16

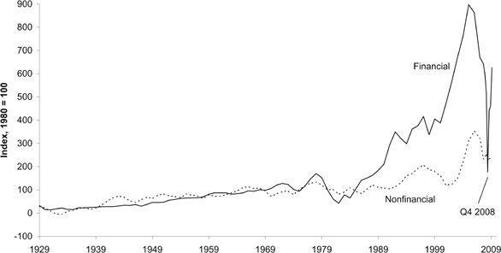

Its share of corporate profits climbed even faster, as shown in

Figure 3-1

. From the 1930s until around 1980, financial sector profits grew at roughly the same rate as profits in the nonfinancial sector. But from 1980 until 2005, financial sector profits grew by 800 percent, adjusted for inflation, while nonfinancial sector profits grew by only 250 percent. Financial sector profits plummeted at the peak of the financial crisis, but quickly rebounded; by the third quarter of 2009, financial sector profits were over six times their 1980 level, while nonfinancial sector profits were little more than double those of 1980.

17

Not surprisingly, bankers’ salaries and bonuses also shot upward. In 1978, average per-person compensation in the banking sector was $13,163 (in 1978 dollars)—essentially the same as in the private sector overall, which averaged $13,142. From 1955 through 1982, the average banker’s compensation fluctuated between 100 percent and 110 percent of average private sector pay. Richard Fisher, chairman of Morgan Stanley in the 1990s, recalled that when he left Harvard Business School in the early 1960s, “investment banking was about the worst-paying job available to us. I started at Morgan Stanley at $5,800 a year. It was the lowest offer I had … I’m sure my classmates who went to Procter & Gamble started at $9,000 a year.”

18

Then banking pay took off, until by 2007, the average banker was making over twice as much as the average private sector employee.

19

Figure 3-1: Real Corporate Profits, Financial vs. Nonfinancial Sectors

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis,

National Income and Product Accounts

, Tables 1.1.4, 6.16; calculation by the authors. Financial sector excludes Federal Reserve banks. Annual through 2007, quarterly Q1 2008–Q3 2009.

This trend was driven by stupendous growth at the top end of the income distribution. In

Liar’s Poker,

$800,000 counted as a big bonus for an experienced trader.

20

In 1990, Salomon Brothers paid its top traders then shocking cash bonuses of more than $10 million.

21

In 2009, it emerged that a single executive at Citigroup—head of a commodities trading group that was loosely descended from Salomon—was due a $100 million bonus.

22

And the real money was in hedge funds; in 2007, five fund managers earned at least $1 billion each for themselves, led by John Paulson, who made $3.7 billion successfully betting against the housing market and the mortgage-backed securities built on top of it.

23

Bigger, more profitable, and richer—the financial sector grew in every way imaginable during the last three decades. Most important, it became more powerful.

BORING BANKING

This is not what a casual observer would have expected in the 1970s, a time when the financial sector composed just over 3 percent of U.S. GDP and paid its workers little more than the private sector overall. For the entire postwar period, finance had generally been what the authors of the Depression-era banking regulations intended it to be—safe and boring. As described in

chapter 1

, the regulatory framework created in the 1930s prescribed a strict separation between commercial and investment banks. Commercial banks had an explicit government guarantee in the form of federal deposit insurance, but paid for it with tight federal regulation. Boxed in by rules limiting the businesses they could engage in, the states they could enter, and the interest rates they could pay (but also protected from competition by those same rules), commercial banking became the stereotype of a conservative, low-risk profession.

Investment banking, though riskier, was a far cry from the trading floor of

Liar’s Poker,

where traders routinely risked hundreds of millions of dollars and ate guacamole out of five-gallon drums.

24

Like commercial banking, investment banking had taken on the features of a cozy cartel. For example, commissions on stock trading had been fixed (since 1792) by the New York Stock Exchange, preventing price competition. Securities firms earned most of their revenues from the traditional businesses of underwriting stocks and bonds (finding buyers for new securities being issued by corporations), providing brokerage services for institutional clients and an increasingly affluent public, and advising companies on mergers and acquisitions. These businesses were built around long-term client relationships, where reputation mattered. Leading banks such as Morgan Stanley cultivated an image as genteel, “white shoe” firms that emphasized client service rather than making a buck. As Nicholas Brady, treasury secretary in the administration of George H. W. Bush and a former investment banker, said in 2009, “When I came to Wall Street in 1954, it was a profession, one that financed the building of this country’s industrial capacity and infrastructure.”

25