13 Bankers: The Wall Street Takeover and the Next Financial Meltdown (7 page)

Read 13 Bankers: The Wall Street Takeover and the Next Financial Meltdown Online

Authors: Simon Johnson

Clearly, something had gone badly wrong. The problem was not that a single bank threatened to usurp political power, like the Second Bank of Jackson’s day; it was that there was no effective check on the private banks as a group, whose appetite for risk had created a massive boom and a monumental bust.

94

The Federal Reserve alone lacked either the power or the will to rein in the excesses of the financial sector. The cheap money it supplied had only encouraged excessive risk-taking. When the crisis finally arrived, the government was left with the choice between bailing out banks around the country and encouraging a further speculative cycle or letting the system collapse and inviting widespread economic misery.

The only force available to constrain the banking industry was the federal government, setting up another showdown between political reformers and the financial establishment. This time, however, the magnitude and severity of the Great Depression created the opportunity for a sweeping overhaul of the relationship between government and banks. And the Pecora Commission, an investigation initiated by the Senate Banking Committee, uncovered extensive evidence of abusive practices by the banks—from pumping up questionable bonds they were selling to giving insiders stocks at below-market prices

95

—providing the political ammunition necessary to overcome the objections of the financial sector. The result was the most comprehensive attempt in American history to break up concentrated financial power and constrain banks’ activities.

96

Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s favorite president was Andrew Jackson.

97

This affinity was not without its ironies. Roosevelt was a man of the Eastern establishment; while Jackson is sometimes referred to as “frontier aristocracy” and had New York allies, he had no affection for the East Coast elite. Still, both men shared an appreciation for the workings of democracy and a fear that unconstrained private interests could undermine both the economy and the political system. In a sense, they were both descendants of Jefferson, and both sought to shift the balance of power between the financial system and society at large. In January 1936, Roosevelt said, “Our enemies of today are the forces of privilege and greed within our own borders.… Jackson sought social justice; Jackson fought for human rights in his many battles to protect the people against autocratic or oligarchic aggression.” Roosevelt also stressed that he was opposed to a “small minority of business men and financiers.”

98

Although Roosevelt faced a far more complex economic situation than did Jackson, his goals were similar: to protect society at large from the economic and political power of big banks. And he was not afraid to confront the bankers head-on; as historian Arthur Schlesinger wrote of the Roosevelt administration’s first months in power, “No business group was more proud and powerful than the bankers; none was more persuaded of its own rectitude; none more accustomed to respectful consultation by government officials. To be attacked as antisocial was bewildering; to be excluded from the formation of public policy was beyond endurance.”

99

The new legislation of the 1930s—primarily the Banking Act of 1933, better known as the Glass-Steagall Act—reduced the riskiness of the financial system, with a particular emphasis on protecting ordinary citizens. The regulatory framework, however, was relatively simple. Commercial banks, which handled deposits made by ordinary households and businesses, needed to be protected from failure; investment banks and brokerages, which traded securities and raised money for companies, did not. The Glass-Steagall Act separated commercial banking from investment banking to prevent commercial banks from being “infected” by the risky activities of investment banks. (One theory at the time—since largely discredited—was that this infection had weakened commercial banks and helped cause the Depression.)

100

As a result, J.P. Morgan was forced to spin off its investment banking operations, which became Morgan Stanley. Commercial banks were protected from panic-induced bank runs by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), but had to accept tight federal regulation in return. The governance of the Federal Reserve was also reformed in the 1930s, strengthening the hand of presidential appointees and weakening the relative power of banks.

The system that took form after 1933, in which banks gained government protection in exchange for accepting strict regulation, was the basis for half a century of financial stability—the longest in American history. Investment banks were also subject to new regulation and oversight by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), but this regulatory regime focused primarily on disclosure and fraud prevention—making sure that banks did not abuse their customers, rather than ensuring their health and stability.

Postwar commercial banking became similar to a regulated utility, enjoying moderate profits with little risk and low competition. For example, Regulation Q, a provision of the Banking Act of 1933, allowed the Federal Reserve to set ceilings on savings account interest rates. Since savings accounts were a major source of funds for banks, the effect was to limit competition for customers’ deposits while guaranteeing banks a cheap source of funds. Limits on opening branches and on expanding across state lines inhibited competition, as did the prohibition against investment banks taking deposits. As a result, banks offered a narrow range of financial products and made their money from the spread between the low (and capped) interest rate they paid depositors and the higher rate they charged borrowers. This business model was emblematized by the “3–6–3 rule”: pay 3 percent, lend at 6 percent, and make it to the golf course by 3

P.M.

According to one leading banking textbook, “some banks frowned on employees working in their offices after hours lest outsiders perceive lighted windows as a sign of trouble.”

101

The result was the safest banking system that America has known in its history, despite a substantial increase in leverage. The average equity-asset ratio—the share of lending financed by owners’ or shareholders’ capital rather than borrowed money—had already fallen from 50 percent in the 1840s to around 20 percent early in the twentieth century as informal cooperation mechanisms developed among banks. But due to the double liability principle (which made bank shareholders potentially liable for up to

twice

the money they had invested), this meant that over 20 percent of bank assets were backed by shareholders’ capital—a stunningly high cushion against loss for creditors by modern standards. After the creation of the FDIC backstop in 1933, the equity-asset ratio fell below 10 percent for the first time in history.

102

In other words, banks took on significantly more debt and, in the process, generated higher returns for their shareholders.

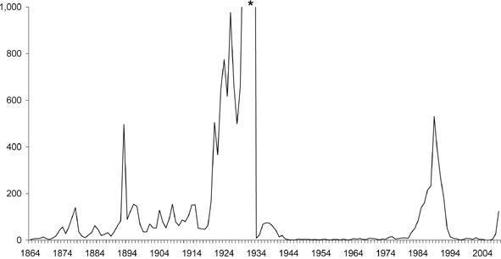

Ordinarily, low equity levels (high debt levels) should increase a bank’s riskiness by increasing the likelihood that it will not be able to pay off its debts in a crisis. Yet despite the increase in leverage, tighter regulation prevented any serious banking crises. As

Figure 1-1

demonstrates, the half-century following the Glass-Steagall Act saw by far the fewest bank failures in American history.

103

But once financial deregulation began in the 1970s, these low equity levels became increasingly dangerous.

104

Figure 1-1: Bank Suspensions and Failures Per Year, 1864—Present

* Actual values for 1930-33 are 1,352, 2,294, 1,456, and 4,004.

Source: David Moss, “An Ounce of Prevention: Financial Regulation, Moral Hazard, and the End of ‘Too Big to Fail,’”

Harvard Magazine

, September–October 2009. Used with the permission of Mr. Moss. Updated with data from FDIC, “Failures and Assistance Transactions.”

Some of the regulations in place during this period may have been excessive. For example, it’s not clear that limiting banks to a single state—a long-standing rule in the United States that was reaffirmed in the 1930s—makes them safer (other than by restricting competition, which increases their profits). Even the need for the Glass-Steagall division between investment banks and commercial banks has been questioned,

105

and recent history has shown that pure investment banks could become systemically important (and therefore qualify for government bailouts) on their own. Still, the regulations of the 1930s were consistent with several decades of sustained growth without major financial crises. No one can conclusively prove that these reforms were essential to postwar economic development. But constraints on banking activities helped prevent the development of massive debt-fueled booms ending in spectacular crashes. The extreme boom-bust cycles of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries faded into memory, while the financial system funneled capital effectively into productive investments.

106

Of course, the story does not end there. The society and economy of the United States remain highly dynamic. New businesses and companies appear and old memories fade away. Political settlements hammered out in previous eras start to seem useless or quaint. Eventually the American tendency toward innovation, risk-taking, and profit-making takes over, and new economic elites arise to challenge the political order.

The laws of the 1930s were intended to protect the economy from a concentrated, powerful, lightly regulated financial sector. In the 1970s, they were beginning to look out of step with the modern world. Bright young minds were inventing new types of financial transactions; banks, particularly investment banks, were making more and more money; and the federal government, charmed by the promised miracles of the financial sector, began relaxing the rules. By the 1990s, Jefferson and Jackson, always awkward topics at any discussion of finance and economics, seemed more irrelevant than ever, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal was under widespread attack. The financial sector was bigger, more profitable, and more complicated than it had been in decades. Productivity was rising steadily, economic growth was strong, and inflation was stable and low. Just as some political commentators thought the end of the Cold War signaled the end of history, some economic pundits believed that this “Great Moderation” heralded a turning point in economic history. Sophisticated macroeconomic theories and wise policymakers, they suggested, had learned to tame the cycle of booms and busts that had plagued capitalism for centuries.

In fact, the 1990s were a decade of financial and economic crises, but they were taking place far away, on the periphery of the developed world, in what were fashionably known as emerging markets. From Latin America to Southeast Asia to Russia, fast-growing economies were periodically imploding in financial crises that imposed widespread misery on their populations. For the economic gurus in Washington, this was an opportunity to teach the rest of the world why they should become more like the United States. We did not realize they were already more like us than we cared to admit.

*

The Tenth Amendment, part of the Bill of Rights, was technically not yet in force, but by the end of 1790 it had been ratified by nine states out of the ten necessary.

*

A trust was a form of legal organization used to combine multiple companies into a single business entity.

*

Lowering short-term interest rates can also help banks by “steepening the yield curve.” Since banks typically borrow for short periods of time and lend for long periods of time, if short-term rates fall while long-term rates remain unchanged, their profit margin—the spread between long- and short-term rates—increases.

*

An alternative explanation, advanced by Barry Eichengreen and Peter Temin, is that the Federal Reserve was constrained by its adherence to the international gold standard; expanding the money supply would have caused a severe devaluation of the dollar.

93

2

OTHER PEOPLE’S OLIGARCHS

Financial institutions have priced risks poorly and have been willing to finance an excessively large portion of investment plans of the corporate sector, resulting in high leveraging.