Read Your Brain and Business: The Neuroscience of Great Leaders Online

Authors: Srinivasan S. Pillay

Your Brain and Business: The Neuroscience of Great Leaders (8 page)

In one experiment, researchers looked at people receiving placebo treatment for pain to see how optimism and anxiety correlated with placebo response.

31

They found that having a less anxious nature and high measures of optimism correlated with greater relief from the placebo. Now, some may say that optimism “fooled” people and it did in a sense. But it also served as an analgesic in the presence of expected relief without relief actually being present. That is, highly optimistic people who have low anxiety have an additional mechanism to treat their own pain.

As a leader or manager, then, if you are experiencing high anxiety and pessimism, you will likely be distracted by the pain—or the pain-related amygdala activation, as described earlier in the book. If, however, you have low anxiety and high optimism, the brain’s attentional centers are shifted away from the pain onto the expectation of reward—which you can even feel. Positive expectations create positive feelings. Positive feelings help you focus away from pain. You have less attention captured by pain and more available to process the tasks you want to.

Concept 2

In the first experiment, we inferred that because optimism decreases pain, it does so through circuits related to the amygdala. Is this actually what happens in the brain? The answer is yes. A study looking at optimism in the brain showed that it caused increased amygdala and ACC activation and that optimism correlated with ACC activation.

32

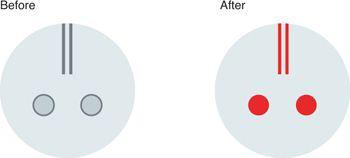

Figure 2.2

represents amygdala and ACC activation with and without optimistic attitudes.

Figure 2.2. Schematic representation of the impact of optimism on the amygdala and ACC

The theory is that the ACC—specifically, the rostral ACC—has a bias toward future positive events over future negative events or any past events. As a result, it activates, and because of its connections with the amygdala, causes the amygdala to activate to this salience as well. Fear becomes less important and is displaced from the front of the line.

Is it better to be optimistic or pessimistic? In this study, the authors provide data to substantiate the following: “Although extreme optimism can be harmful as it can promote an underestimation of risk and poor planning...a pessimistic view is correlated with severity of depression symptoms....” Furthermore, “a moderate optimistic illusion...can motivate adaptive behaviour in the present towards a future goal, and has been related to mental and physical health....”

These authors conclude, “expecting positive events, and generating compelling mental images of such events, may serve an adaptive function by motivating behaviour in the present towards a future goal. [...] Simulating negative events may interfere with daily activities by promoting negative effects such as anxiety and depression....”

The application:

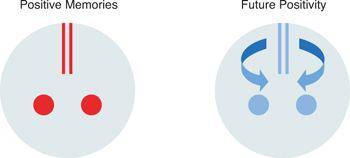

It is important for leaders to understand that having a moderate optimistic bias for future events can help the brain prepare to focus on its goals by capturing its attention more than fear. Future positive events are more impactful than past positive events on the ACC and on the amygdala. (They are actually experienced as being closer in time.) That is, they replace fear that holds the amygdala captive. Optimism in the brain is permission to focus on a goal. It is simply the beginning of imagination and helps imagination connect with action.

For leaders and coaches, focusing on future positive events has the most powerful effects on the brain’s ability to focus on its goals (more even than past positive effects or any negative effects).

Figure 2.3

illustrates the different impacts of reflection on past positive events and positivity about the future.

Figure 2.3. Schematic representation of the impact of positive memories versus future positivity on the amygdala and ACC

This imagining appears to be more accessible, and the brain somehow makes future positive events seems closer. When you’re developing imagination exercises then, focusing on potential positive events is helpful in allowing for a more goal-directed process. Here are some specific examples of optimistic questions that leaders, managers, or coaches can ask to enhance goal-directedness (and increase ACC and amygdala activation away from fear):

• Where do we want to end up?

• What will we all get if we achieve what we want?

• What gains will we make?

• If, for a moment, we believe that we are going to reach our goals, what would that mean for all of us?

• Where can we picture ourselves if this works out?

So how does this brain-based knowledge optimism affect what leaders do? Here are some key points to keep in mind:

• Leaders can start by examining the past, but the brain should be left with imagining positive future events. In other words, never end a talk with uncertainty if your aim is to increase goal-directedness. There are different kinds of imagery in sports coaching: Cognitive General, Motivational Specific, Motivation General-Mastery, and Motivation General-Arousal,

33

all of which have been used to improve performance with positive images. (See

Chapter 5

, “The Challenge Prior to Change: How Brain Science Can Bring Managers and Leaders from Idea to Action Orientation,” for more detail.)

• Revisit the expected positive outcomes over and over again. Encourage employees to sketch out a timeline and their progress toward their goals.

• If employees are stuck, tell them to forget

how

they will get to where they want. “Stuckness” induces negativity and pessimism. Trying to get people who are stuck to force themselves to figure out

how

to get where they want will only increase amygdala activation in a way that will not increase goal-directedness. The first step is to abandon this stuckness and pessimism. For example, you can say the following: “Okay, let’s accept that you’re stuck. Now, let go of that. I want you to imagine that you have reached your goal. What would that mean?” (You will often realize that the real stuckness is in imagination.)

• When people are in conflict, do not merely examine pros and cons. A more productive approach when conflict is too high is to ask each party how things would look if they both got their way in a manner that served the company goals. Then, work backward from this optimistic point of having solved the problem.

Hope and optimism are critical tools that leaders can use to rewire their brains and the brains of their followers. It is important to remember that optimism in this context is not just “wild” speculation or cheerleading. Instead, it is a gentle reframing and emphasis on goals and a non-anxiety-provoking vision of the future. There are those leaders who will argue that it is not realistic to be optimistic,

and they may be correct. However, the argument here is that optimism builds the brain’s connections differently than realism and provides relief from a burning, red-hot amygdala.

When you have hope and optimism, you have an automatic way of replacing fear in the line of emotions asking for attention from the amygdala. That is, hope and optimism decrease the emotional distractions that affect thinking. As a result, leaders can think more effectively. We now know that optimism actually “opens up” the brain for less anxiety-driven processing. As a result, it is not a “soft” attitude; it actually impacts how your brain searches for solutions. It is a particular brain environment that replaces fear as the number-one emotion in line for amygdala processing.

Why Positive Emotions Matter

The concept:

Happiness itself affects what you remember. Although people who are sadder believe in the “objective” reality of their memories, research shows that the way we feel determines what we focus on in remembering past events.

34

Furthermore, research also shows that happier people achieve greater success when people are making decisions about them.

35

When going to an interview, for example, this bias may come into play. Emotional expressions may also influence perceptions of social dominance. People tend to view happier, neutral, or angrier men as more dominant than sadder men. Sadder women are also viewed as less dominant. Thus, when leaders are concerned about social perceptions, knowing these facts may be helpful to them.

36

Studies have also shown that people solve insight or creative problems better when in a positive mood (assessed or induced). A recent study has shown that when a person’s mood is positive, this affects brain activity prior to solving a problem in a manner that leads to better insight and analysis.

37

Specifically, positive mood alters activity in the ACC during the preparation phase and results in an improvement in attention, insight, and problem-solving ability. Note that this study specifically looked at insight-based solutions versus analytical solutions. Thus, when justifying the need for mood changes, we may support this by reminding leaders that the brain’s ability to produce insight solutions improves when people are happier. The thought behind this is that feeling good increases the chances of flexibility in thinking and promotes a more “global scope of attention.”

38

Note that insight and analytic problem solving work through different brain mechanisms. Some of the differences between these types of problem solving are the following (you do not need to remember the brain regions—just that there are differences between insight and analytical solutions): (1) Insight solutions activate the right hemisphere more; (2) insight solutions activate the right temporal lobe more; (3) verbal insight solutions activate a distributed neural network that includes bilateral activation in the insula, the right prefrontal cortex, and the anterior cingulate.

39

Furthermore, the rostral portion of the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex showed a sustained increase in neural activity during the preparatory interval before participants actually see problems, and stronger ACC activity occurs prior to trials solved with insight than those solved more analytically.

40

The fact that happiness increases this suggests that this specific component of insight production is enhanced.

The application:

Coaches can tell leaders who are stuck in finding solutions that their solutions may need to emanate from insights rather than analytic processes. To enhance the possibility of this, focusing on the positive and improving one’s mood state have been shown to increase flexibility of thinking and, through this, vital insight regions including the ACC in the human brain. They may further explain that although analytical solutions may not be prone to improvements with feeling better and focusing on the positive, insight solutions are.

For many businesses I have worked with, analytic problem solving is a way of not standing still. It creates the impression that a problem is being solved when it is not really being solved. It is just being broken down into different shapes and sizes and put back together in

a different way. Insight gives birth to a whole new way of thinking. Positive thoughts give your brain permission to travel where it has not travelled before. It is more nerve-wracking because the unknowns are greater, but you are much more likely to find insight solutions that way—and the brain science supports this.

The Psychology of Mindfulness

The concept:

Mindfulness

is our capacity for awareness (or self-knowing), and a recent paper outlined why this may be so important in the business environment as well.

41

In this paper, called “The Practice of Mindfulness for Managers in the Marketplace,” the author states the following: “Partly because of the brilliance of our scientific and techno-logical triumphs, we have dissociated ourselves from the spiritual world, sought outside for answers that can only be found within, denied the subjective and the sacred, and over-looked the latent capacities of mind. However, there exists within us, unexplored creative capacities, depths of psyche, and states of consciousness, undreamed of by most people” (Walsh and Frances, 1993). To capture the importance of mindfulness in our volatile economy, the author points out a quote: “You cannot stop the waves, but you can learn to surf.”