Your Brain and Business: The Neuroscience of Great Leaders (3 page)

Read Your Brain and Business: The Neuroscience of Great Leaders Online

Authors: Srinivasan S. Pillay

Table 1.1. Debunking Organizational Myths with Brain Science

•

Providing further insights and evidence—

At times, the usual interventions may not work when trying to help a leader change behavior. The leader may be resistant to change and may say, “I’ve always done this a certain way, and I can’t do it any differently.” Here, we can use the language of neuroplasticity in the dialogue. For example, rather than saying, “Of course you can change and you have to,” a coach may say, “Brain science teaches us that the brain can change even in adulthood; in fact, the brain can form new connections and pathways and by trying out something new, your brain can rewire itself in time.” Here, the coach circumvents the resistance to change by overtly describing a biological reality: that the brain can change. Another example would relate to visualization. Many people know that visualizing goals is helpful, but this often sounds too “New Age” or unsubstantiated. In this book, we will examine the biology of visualization and a new language of brain science to understand this phenomenon entirely differently.

•

Providing a system for targeted interventions—

When we use brain biology to explain phenomena, we may also extend this to use biological principles to construct interventions or strategies. For example, in the example of unconscious fear given earlier, it is often difficult to just ask a leader to stop his or her unconscious fear. If the leader is not conscious of it, how will he or she stop this? By understanding that the amygdala (the brain’s emotional center) connects to the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), we can target the functions of the ACC (the brain’s conflict detector) to reach the amygdala. Details of these interventions will be provided later in the book. Another example would be, how do coaches increase the commitment of a client to a new plan of action in the face of old habits? Or how do managers increase the commitment of people who report to them? By understanding the brain science behind commitment (which requires activation of the left frontal cortex), coaches and managers can then develop interventions that target the left frontal cortex (explained in detail later). Thus, brain science can help us construct active interventions as well.

•

Developing coaching protocols and tools—

The aforementioned piecemeal interventions can be incorporated into a coaching protocol so that a significant part of the coaching may

include the biological basis and related interventions. For example, I was hired by a company to work with senior leaders to help them increase their power and influence during difficult conversations. These leaders had found that the people they were reporting to were often closed, autocratic, and frustrating. By understanding the brain basis of difficult conversations, we can construct checklists as part of coaching protocols to help leaders have an organized approach to developing a new skill. Understanding brain functions allows us to develop a coaching protocol with different targets than one that looks solely at behaviors.

More Examples of How Brain Science Concepts Enhance Coaching When Dealing with Problems and Traps That Leaders Face

Problems

are overt issues that leaders, managers, coaches, and clients can understand.

Traps

relate to unforeseen consequences that executives or coaches may face. In both of these situations, brain science can be very helpful to executives or coaches looking for alternate explanations and strategies.

The following examples illustrate the business problem, the brain science concept that relates to the problem, and the specific application of this concept to improving productivity in the business environment.

1. The leader is working too much in isolation

When leaders make unilateral decisions, this can impact the company in very negative ways. It erodes coherence, trust, and productivity. When coaches work with leaders whose social intelligence is challenged in this manner, they are often faced with the difficulty of communicating the importance of involving as many levels of the company as possible in decisions. Leaders see this as too labor intensive and often think that they are muddying the waters when they take too many opinions into consideration. As a result, they steer away from involving other people. How can you, as a coach or manager, use the language of neuroscience to communicate why this does not always work well in the company?

The concept:

The neuroscientific concept that can be used here is the following: Much like the way in which a company works, brains also have a hierarchical structure that involves a “top-down” communication of information. In a company, a CEO may communicate information to a senior manager; in the brain, that executive function is served by the frontal lobe. That is, the final decision to act makes its way to the frontal lobe before action occurs. However, prior to this decision being made, there are multiple networks in the brain that have to have their say. Much like a successful company, the brain relies on the input of its various parts prior to making a decision. That is, the brain acts as a set of collaborating brain regions that operate as a large-scale network.

The application:

Coaches can use this information to remind leaders that the company operates due to the brains of all the people who are employed. All of these brains together form “the company brain.” The leader is that part of the company brain that has to make the final decision: He or she is the frontal lobe of the company brain. Let’s reflect on how the frontal lobe functions: We know from extensive research that if there are insufficient inputs to the frontal lobe, it cannot make the correct decisions. Just as the frontal lobe of any individual brain needs inputs from the emotional center in the brain—the risk register, the reward center, and many other regions—before it can make a decision, the company’s frontal lobe also needs this information. In the case of the company, these other “inputs” are other people. Coaches and managers can introduce leaders to the importance of working together by using this metaphor.

Furthermore, CEOs who form these networks prior to becoming leaders are more likely to be successful.

4

In the rise to greater responsibility, it is important for leaders to conceive of themselves much like the frontal lobe of the brain in “reaching out” to other “brain regions” within the company during the rise to leadership rather than after they have been nominated to that position. These frontal lobe functions in

the business environment may involve bridging, framing, and capacitating

5

—all ideas that are about relating and making the business environment relatable.

2. The leader believes that emotions have nothing to do with the final decision

The concept:

There are two types of reasoning: hot and cold reasoning. An example of cold reasoning is a straightforward arithmetic operation—although even this is not as cold as we think! Cold reasoning usually activates short-term memory centers only, without activating regions involved in “hot” reasoning. Very few thinking process are actually cold. Even reasoning that appears cold is motivated when people have an emotional stake in it. This is almost always the case in business. Hot reasoning, on the other hand, activates the brain’s accountant (the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, or vmPFC), the conflict detector (the anterior cingulate cortex, or ACC) and the “gut interpreter” (the insula).

6

Activation of these brain regions is critical to making effective decisions.

Consider, for example, the case of companies who were fearless about lending money to people for mortgages. Without this fear, they lacked the information that was necessary to judiciously distribute money. Fear is an emotion, and it needed to be part of the equation before money was lent. On the other hand, if fear dominated the thought of people who invented the airplane, we might never have been able to fly. In each case, the emotion of fear is necessary to ensure adequate precautions. In the former case, it discourages lending, whereas in the latter case, it encourages innovation with safety.

Scientifically, we know that hot reasoning matters because in an experiment using deductive reasoning, a group that received logico-emotional training moved from error to logic, whereas the group that did not receive the emotional component of this training still made many errors.

7

This training involved teaching people to be in touch with their emotions and activated the brain’s accountant (vmPFC).

The application

: It is not easy to tell most leaders who are opposed to emotions being part of decision-making that they need to be “in touch with their emotions.” Neuroscience can help to provide more acceptable language. As a coach, you may tell leaders that their brains’ accountant relies on emotional data to make the correct decisions and that experiments have shown that when the accountant corrects for errors in the brain, it is largely because it makes contact with emotional centers in the brain. You may also remind leaders who are sensitive to “emotions” that emotions are really just electrical impulses travelling through the emotional centers in the brain. The accountant in their brains needs a read on this electricity prior to making a decision.

Following acceptance of this explanation, you will have created a logical permission for the leader to be more open to your subsequent emotional and social intelligence development initiatives. In fact, a leader’s emotions may play a very important role in leadership effectiveness.

8

3. The leader is not comfortable making a necessary change

The concept:

When leaders say, “I am just not comfortable with that,” when they resist moving in the direction of new decisions, they need to be finely attuned to this sense of discomfort when making decisions, even when they can’t account for it. However, in certain situations, this discomfort may not indicate that a decision is wrong, but that it is different. Recent research has shown that this discomfort, also called

cognitive dissonance

(details are explained in

Chapter 6

, “From Action Orientation to Change: How Brain Science Can Bring Managers and Leaders from Action Orientation to Action”), is essential to sticking to a new action. Brain imaging research has shown that to remain committed to a new decision, the left frontal cortex of the brain has to activate. This part of the brain will not activate without cognitive dissonance.

The application:

When leaders are uncomfortable about a new decision, ask them to hold onto the discomfort while you take a look

at the issue. To help them actually do this, you can tell them that brain imaging studies have shown that maximal discomfort is a necessary initial step to stimulate that part of the brain that will increase commitment to a new decision. Paying attention to variables such as “cognitive dissonance” has been recognized as fundamental to the field of behavioral finance.

9

4. The leader is too anxious

The concept:

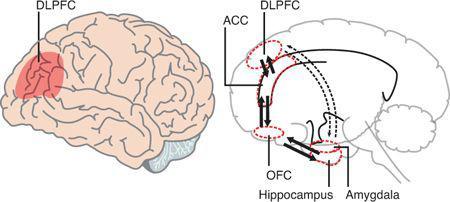

Anxiety activates the amygdala—the fear and anxiety center in the brain.

10

This part of the brain is connected to the thinking parts of the brain: in particular, the prefrontal cortex

11

and ACC (see

Figure 1.1

).

Figure 1.1. DLPFC connections to anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), orbitofrontal (OFC) cortex, amygdala and hippocampus

There are two major subdivisions of the prefrontal cortex:

•

The DLPFC (dorsolateral prefrontal cortex)—

This is the short-term memory store.

12

,

13

New information coming into the brain is registered here and stored before it can be sent to long-term memory. Thus, excessive anxiety disrupts the integration of incoming information and short-term memory is compromised.

•

The mPFC (medial prefrontal cortex)

14

—

The inner parts of the PFC (mPFC), shown in

Figure 1.2

, are responsible for various functions such as calculations of risks and rewards,

15

motivation,

16

memory retrieval,

17

and other very important functions in decision-making.

Figure 1.2. The medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC)