Read Your Brain and Business: The Neuroscience of Great Leaders Online

Authors: Srinivasan S. Pillay

Your Brain and Business: The Neuroscience of Great Leaders (22 page)

The Entrapment of Context

The concept:

One of the major challenges to new learning is “context.” Experiments have shown that context is a major determinant of conditioning.

6

–

8

Here are some examples of how context influences our decisions:

• “That skirt is too sexy for work.”

• “I have to show my serious side at work.”

• “Just walking in the front door makes me nauseous.”

• “Just seeing my boss makes me nervous.”

• “Female bosses are always so touchy-feely.”

Context can involve a place, person, or role that has become defined and influential within one’s belief set. However, regardless of this external context, context is seen and defined by our brains.

A large number of brain structures are implicated in contextual conditioning in humans.

8

Of these, the amygdala and hippocampus stand out.

7

The automatic emotional reactions of the amygdala to context and the shaping influences of long-term memories of the hippocampus form the canvas upon which all thoughts are experienced. Thus, they form automatic and relatively fixed reactions to events in the environment. Sometimes, these effects are so strong that we have to choose another canvas upon which to view our thoughts. This is the role of the manager or coach. A coach’s job in contextual conditioning is to assist the client in redefining the context so that new behaviors can emerge. In effect, it is to change amygdala activation.

9

Again, remember that internal context (the brain) is what defines how external context is experienced.

For contextual conditioning to be reversed, the brain’s accountant (the vmPFC) has to inhibit amygdala activation.

10

(Note that the amygdala has multiple nuclei that have different functions here; these details are less applicable at the current time.)

11

Also, the conflict and attention center (the ACC) is activated during extinction of the automatic response. That is, when you try to reverse a habit, the brain

goes into a state of conflict and tries to hold onto the habit, using emotional distress (amygdala activation) as the threat if you change.

The application:

It is important be attentive to the influences of conscious and unconscious fear on behavior. When the amygdala is overstimulated over a period of time, it continues to send messages to the hippocampus, especially during contextual fear conditioning, and vice versa. In other words, long-term memories shape the meaning of current fears and may distort them or add to them. This is the reason for bringing the attention to the moment—the past is too distracting. We have to remember that memories are not just cognitions and not just thinking. They are emotions as well. In fact, emotional memories are some of our strongest memories. And sometimes, they are intangible and unrecognizable but very impactful indeed. Thus, when you’re trying to change, it is important to ask, “What is the context of this need to change?” For example, does it have to do with general life boredom? Does it have to do with pain? Does it have to do with power? One can benefit from understanding the details of these hippocampal memories in order to stand a better chance of progress. Managers or coaches can tell team members the following: “I think that your desire to change is admirable and important. The general idea that you have ‘that life should be better’ is true. But this is not news to you. If you have known this all along, why have you not changed? Not because you’re ignorant...or incapable. But because to truly change we have to understand the context in which this change is occurring. For change to occur the previous context has to be removed and a new one introduced. That is because ‘context’ refers to the long-term memories that shape your current thinking. When you want to change, it opens up the can of worms in your memory vault and they immediately start to join your current goals. These memories can hold you back from change if their power is not disengaged. To disengage their power, we can start by labeling them and taking away their unconscious energy.” Alternatively, the managers or coaches

could say this: “The change you want does not occur in isolation. Every thought you have is joined by memories from your long-term memory. Something in the past may be holding you back, and we need to balance understanding this with focusing on the future. Too much of either will leave you either paralyzed or in a superficial change.”

I see this often when companies want something to change but are attached to their obstacles. “It is impossible to report to this outside governing force. They always delay things and have input despite having no knowledge.” This already tells the brain that something is not possible. It does not put the brain in solution-seeking mode. Instead, the brain makes changes in the context of “impossibility.” This is akin to shifting the deck chairs on the

Titanic

instead of jumping overboard.

Motivated Reasoning

The concept:

The final challenge to change is called “motivated reasoning.” How often have you been in a business situation where someone claims to be rational but you just can’t put your finger on why this does not seem to be the case? This person presents you with all the “facts” about why he or she cannot change, but the “facts” justify the stuckness, and you can’t seem to challenge this? These beliefs are what we call self-limiting beliefs, and they are extremely powerful because they are almost impossible to refute. Understanding the existence of this concept can aid you in helping people to change.

In one experiment, brain images were collected in committed partisans during a political election. Subjects were presented with reasoning tasks involving judgments about information threatening to their own candidate, the opposing candidate, or neutral control targets. Motivated reasoning was associated with activation in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC, the accountant), anterior cingulate cortex (the conflict detector), posterior cingulate cortex, insular cortex, and lateral orbital cortex. It was not associated with neural activity in regions previously linked to cold-reasoning tasks and conscious (explicit) emotion regulation.

Thus, not all forms of rational thinking are purely rational. Motivated reasoning is a way of regulating our emotions in which the brain converges on judgments that minimize negative and maximize positive feeling states associated with threat to or attainment of motives.

12

That is, these emotions serve as motivators for the “tight” reasoning that occurs. In effect, the emotions direct attention toward the thought that supports the feeling investment.

For example, Jack P. was a high-flying CEO who had risen to the top very fast. He did this when he was single. He then married and had two children, and his life and responsibilities changed. His home life was filled with strife, and he brought this to work every day. He began to feel miserable. When he addressed things at work, he felt that they were “doomed” and started to become very negative. This impacted his senior managers and their teams, and performance started to wane. Jack pointed to all the rational reasons that he had become displeased with things (and they were true), but he ignored the fact that this “rational” thinking was coming from an emotional mindset that wanted to find problems rather then solutions. When he realized that his reasoning was motivated by his own emotions, his first step was to separate out his home life from his work life. Miraculously, both his home life and work life became much better.

The application:

When people express “I can’t,” aside from mentioning self-limiting beliefs, you can ask them what emotions are behind their thinking. When they say that they can’t make a change because of a “rational reason” but are stuck nonetheless (e.g., I can’t spend the time looking for a new job because I need the money right now), you can ask them to examine the underlying motivators. This will bring forth emotions that need to be added to the equation. Also, the assumptions underlying the fears of change can then be examined. Coaches can explain to people that there are two kinds of rational thought: cold and motivated. Almost all forms of thinking in

decision making are motivated.. Managers, leaders, and coaches can tell their teams this: “Your brain activates different regions when your thoughts are rational and when they are motivated but appear to be rational. In almost all work-related decisions, reasoning is not cold. For you to stand a better chance of change, we need to examine the motivators behind your thinking that are most likely unconscious. To do this, I will ask you a few questions. What would happen if you did change? How would you cope if you needed six months to find a new job? Is there a chance that you will burn out staying at this job? Are you just delaying the no-job situation?”

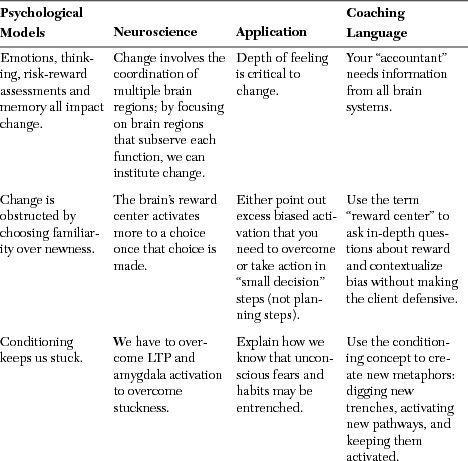

Table 5.2

illustrates how to translate what we learn from brain science in the business environment.

Table 5.2. Challenges to Change

The Fundamental Concepts in Change: A Working Model

The most obvious dimension of change is a linear one defined by time, as shown in

Figure 5.10

.

Figure 5.10. Linear model of change

Working with this model, most coaches end up dragging their clients to an outcome, which even if it is measurable, is very difficult to maintain. I call this the coiled-spring approach, which is illustrated in

Figure 5.11

.

Figure 5.11. Tight and stretched coiled springs

The two fundamental problems with this approach can be seen when we consider what will happen when you let go of the spring (i.e., when the manager or coach leaves): Either the coiled spring will return to its former position, or, if it does not return to its former position, it will lose its power and identity as a spring.