Your Brain and Business: The Neuroscience of Great Leaders (35 page)

Read Your Brain and Business: The Neuroscience of Great Leaders Online

Authors: Srinivasan S. Pillay

For example, Chris B. is the VP of sales for a large company. He found that his senior managers were unable to work effectively with the sales force, which had become very disillusioned. When he met with the managers individually, he found that only some of them were able to motivate their sales people. When he learned of the mirror neuron mechanism, he recognized that there was more that he could do. Therefore, he got all the managers in the same room to strategize around what to do. The end result was that the group felt motivated as a whole to start a new sales initiative to divide the sales forces into competitive teams, so that the teams could compete with each other and at the end of the month the best team would win. This got the team spirit to spread, and the competition served as a contagious driving force, especially because they reviewed scores on a weekly basis. The team with the most sales would win. This kind of internal competitive spirit can be very contagious, and relying on mirror neuron mechanisms to drive this process can be very helpful.

Questions that a manager and leader can ask include the following: What emotion do I want to stop en masse? What do I want to spread en masse? What mechanisms (e-mail, individual meetings, newsletters) do I want to use? How can I keep this emotion going? If this emotion is interrupted, how can I re-create the new emotion so that I can continue spreading it?

If you invest in a few key players, you can efficiently spread a new emotion within the company.

•

Working with 360 feedback forms—

In 360-degree feedback (feedback that comes from all people interacting with an employee), mirror neuron mechanisms can come into play. A specialty investor I worked with was critiqued for not providing detailed-enough feedback to the general investment team on the specialty sector. The group complained that they did not get enough information about the models that the specialty investor used and wanted to know more. They also said that they thought that the specialty investor ought to visit them in their offices more to share his ideas. The specialty investor responded to this feedback by creating more models and increasing his communication, but he also was enraged that the feedback to him was so hierarchical and that it was a waste of his time. The larger group then got some of this feedback from him and their rage continued to grow. This continuous “rage exchange” was initially viewed as an exchange of rational sentiments, but it can also be viewed as mirror neuron mechanisms that are out of control. Under the pressure of a volatile stock market, each party’s anxiety had escalated. This volatility in the stock market had led to volatility in mood that they directed against each other. Although the arguments appeared to be “rational,” they were in fact rational narratives made up by an anxious brain. Research shows that under situations of intense anxiety, attention is biased toward threat. Thus, each party was looking more at what threatened them than they might have if they were not anxious, and they were “sharing” their anxieties through mirrors. With these insights, managers can step away from 360 anxiety mirrors and recognize that an appropriate intervention might be to help calm down both parties.

•

Counter-mirror training—

The beauty of the human brain is that it can be retrained to behave in different ways. However, waiting until chaos occurs is not the best way to go about this. Leaders, managers, and coworkers will be in a strong position if they start their mirror neuron training now. But how do we know this is even possible?

A recent study has shown that “counter-mirror” training can reverse the automatic mirroring shown in the brains of observers.

1

This implies that people can be trained not to mirror the chaos going on outside of themselves.

Here’s a basic guide on how to use counter-mirroring:

- Identify what you are feeling.

If you are feeling anxious, afraid, sad, or angry, ask yourself, “Is there anyone else with whom I interact in my daily life that appears to feel the same way?” If there is, proceed to step 2. - Entertain the following hypothesis:

“The reason I feel this way may be exacerbated by someone else in my home or work environment. Because they are anxious, fearful, sad, or angry, I may feel the same way. My brain may be mirroring what they are feeling.” - Stop all attacks and complaints temporarily.

Recognize that anything that you say will not be entirely what you are feeling. It is also reflecting the sum total of other people’s emotions in your brain. - When communicating while mirroring, take a step back and ask the following question:

“What would a complementary feeling or action be?” (It is being increasingly found that the mirror neuron system is developed for imitating as well as complementing other actions and perhaps emotions.

2

)

For example, if the specialist investor from the earlier example were to use counter-mirroring, he would state the following:

- I feel anxious and attacked.

- The general investment team also feels anxious and attacked.

- Let me try to understand why we all feel that way. Ah! The stock market is volatile and we are seeking “reasons” to account for our background anxiety about this.

- My complementary actions would be to calm down and to realize that my emotional mirrors and systems are reflecting their emotions in addition to my own. Perhaps we can figure out a way to decrease our common anxiety.

A manager can help moderate such a discussion.

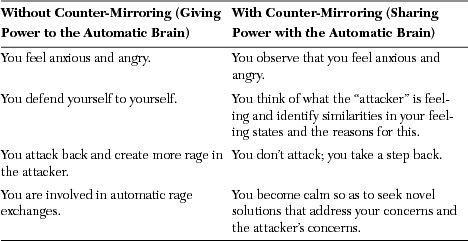

Table 8.1

shows the differences with and without counter-mirroring.

Table 8.1. How Counter-Mirroring Makes a Difference

If this counter-mirroring is practiced beforehand, people can be prepared to have automatic “calm” responses to external chaos. In fact, it is now increasingly believed that the mirror system is a product of social interactions and social learning

3

rather than being intrinsic and unchangeable. Thus, counter-mirror neurons provide a way of transforming automatic imitation into a considered response. Counter-mirroring is facilitated by sympathizing rather than empathizing as a first step (“That is terrible” as opposed to “I feel terrible”).

When mirroring is out of control, anxiety can spread throughout an organization. Counter-mirroring allows all individuals to function with their authentic feeling states rather than the feelings from someone else that they are imitating.

An Approach to Cognitive Perspective Taking

Two aspects of empathy are relevant in the business environment.

4

One involves “feeling” what another person feels (such as the shared feeling states when mirror neurons activate). The other aspect involves “thinking” about what another person feels. The latter is also called “cognitive perspective taking.” A recent study has shown that emotional empathy involves the mirror neuron system (inferior frontal gyrus), whereas cognitive perspective taking involves the brain’s accountant (vmPFC).

5

Thus, we know that if we want to enhance our cognitive understanding of another person’s feelings, we have to think of vmPFC interventions. But why would this be relevant in the business environment?

Three studies have shown that in negotiations, cognitive perspective taking shows distinct advantages over empathy in that it increased the individuals’ ability to discover hidden agreements and to both create and claim resources at the bargaining table. In fact, empathy was at times detrimental to discovering a possible deal and achieving individual profit. These results were true when a negotiation did not appear to have a solution initially and when there were multiple levels of negotiation requiring trade-offs.

6

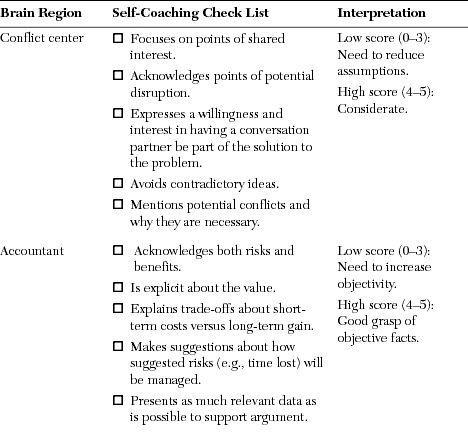

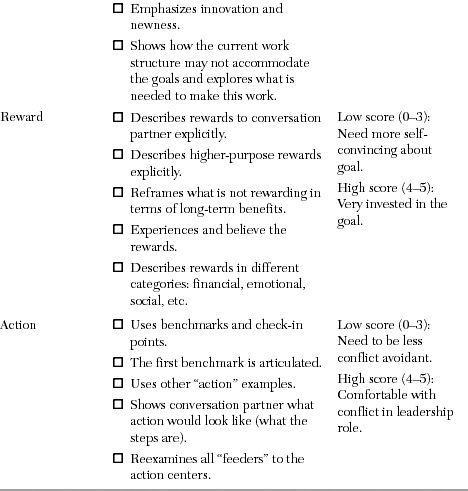

Let’s now consider some cognitive perspective interventions. When there is a difficult conversation, how can we enhance our cognitive perspective taking using brain science?

Table 8.2

provides a systematic approach to thinking about what is going on in the other person’s brain. This is an exploratory tool that helps to organize the planning of a difficult conversation or one in which you want to increase your influence. By checking yourself against this table, you can increase your own insights about the other person’s brain. The table is a very useful guide to handling difficult conversations, and with repeated use and practice, it will lead to an improvisation that you can apply in semi-automatic ways (for example, I need to be sensitive to keeping ACC and amygdala activation low, not overload short-term memory, and continue to try to

understand

what the other person is feeling rather than just automatically

feel

what he or she is feeling).

Table 8.2. Check-List to Enhance Cognitive Perspective-Taking

I used this table with senior managers with an engineering background, all from the same company, whose task it was to engage external collaborators around new approaches to technology when those external collaborators were resistant to change. The table can be used to review approaches associated with each brain region to reach the desired outcome, which in this case was a less conflicted, more open conversation partner in the collaborator.

The general approach for when negotiations or conversations are difficult is as follows:

• Prevent the conflict detector of the conversation partner (CP) from firing: Start by establishing shared priorities.

• Prevent overactivation of the CP’s amygdala to prevent him or her from going into survival mode: After articulating the new proposition, you may need to reframe, reengage, resolve, reassess, and refocus (ACC interventions) in an active and dynamic way until you allay obstructive anxieties.