Young Woman and the Sea: How Trudy Ederle Conquered the English Channel and Inspired the World (23 page)

Authors: Glenn Stout

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Nonfiction, #Retail, #Sports, #Swimming, #Trudy Ederle

Swim meets that featured both Weissmuller and Ederle drew crowds unlike any the sport had ever seen. Young girls and women swooned before Weissmuller and looked up to Trudy as a kind of role model. Not until Mark Spitz emerged in the early 1970s did the sport of swimming enjoy such a figure as dominant and charismatic as either Weissmuller or Ederle.

At Long Beach the crowds were enormous. Weissmuller and Ederle were the reason. Weissmuller didn't disappoint—he defeated Ranger Mills, the metropolitan New York one-hundred-yard champion, by more than two seconds in their one-hundred-yard race. But it was Trudy who won the battle of the headlines.

Hers was a five-hundred-yard handicap event against two other WSA swimmers, Virginia Whitenack and Ethel McGary. Both were accomplished—Whitenack, one of the WSA's up and coming stars, was the metropolitan champion over 880 yards, while McGary held a variety of titles from 100 to 500 yards and earlier in the week had won the national AAU long-distance championship, a three-mile race in which Trudy, now focusing on shorter events in advance of the Olympics, had not competed.

Nevertheless, when racing against Trudy, each girl was provided with a head start in a handicap race. Whitenack received a fourteensecond lead and McGary a nine-second jump. By the time Trudy entered the water, Whitenack had already made the first turn and McGary was in the process of doing so.

It wasn't enough.

Trudy responded with the best single-day performance of her career to date, at least equal to her Labor Day effort in 1922. She set world short-pool records at every imaginable distance officials had thought to time—200 yards, 220 yards, 300 yards, 300 meters, 400 yards, 440 yards, and 500 yards, lowering the record over 500 yards by nearly three seconds, finishing the course in 5 minutes 52 seconds. Moreover, despite giving the other girls a head start, she managed to beat Whitenack by seven yards and McGary by fifteen feet.

It was an absolutely stunning, jaw-dropping performance, made even more so by the apparent ease with which she had swum. The

New York Times

reporter covering the event described her as swimming "a slow, easy crawl. She seemed to be putting such little effort into it that the crowd was amazed when the times were announced." A month later she traveled to Hawaii to face members of the famed Huimakani Club, a Hawaiian team that some swim observers believed was better than the WSA, and whose top swimmer, Mariechen Wehselau, some believed was even better than Trudy.

Not so. Over a three-day period Trudy broke her own world records in the 100, 200, and 400 meters. She was the most dominant athlete in her sport in the world—no one else, not even Johnny Weissmuller, was even close.

Although some men failed to recognize her abilities, those who did did not bother to hedge their words. At the end of the year Grantland Rice, who had earlier accompanied Trudy and the other WSA swimmers to Bermuda, wrote a syndicated column in which he tried to select "the single greatest competitive achievement of 1923." Rice offered a laundry list of some fifteen accomplishments, ranging from Helen Wills's victory in the American women's tennis championship to golfer Bobby Jones's victory at the U.S. Open, Bill Tilden's fourth consecutive U.S. title in men's singles, and Babe Ruth's two home runs in one World Series game.

But in Rice's estimation no one quite matched Trudy Ederle. "Breaking one record is often a great year's work," he wrote. "Smashing seven in one year is a monumental affair."

T

HERE WAS NO PLACE

like Paris.

As the 1924 Olympics approached, the French government and the IOC were determined to show the world that Europe was on the move and had rebounded from years of wanton carnage. Later romanticized by expatriate American writers such as Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Gertrude Stein, in the 1920s Paris was the most exotic city in the world, in Hemingway's terms "a moveable feast," a place where culture flourished, where the jazz was hot, wine flowed, and talk of art and literature filled the air. The Olympics promised to be yet one more beacon for the City of Light, and after the dismal conditions that plagued the 1920 Olympics in Antwerp, where swimmers and divers competed in a murky canal full of fetid water of dubious origin, the French pulled out all the stops to make the 1924 Olympics a celebration not only of France and French culture, but of the world itself.

After her stellar performance in 1923, all that remained for Trudy to accomplish in her sport was to earn a place on the Olympic team and then win the expected gold medals. She spent the winter training in Miami with Helen Wainwright, Aileen Riggin, and other WSA stars and then embarked on an abbreviated indoor schedule that took her to such exotic locales as Omaha, Nebraska, Brookline, Massachusetts, Buffalo, and Chicago, where she continued her streak of spectacular swimming. In April her Olympic prospects achieved another boost when Lou Handley was named the coach of the women's swimming team; Johnny Weissmuller's coach, William Bachrach, was named coach of the men's squad, thus ensuring that the two top American prospects for winning medals would be accompanied by their own personal coaches. As summer approached, Trudy cut back on the number of meets in which she competed in order to focus on the upcoming Olympic trials.

Trudy's place on the team was not a given—despite her multiple world records there was no mechanism to name her to the team unless she qualified at the trials. She still had to earn her place, one of 135 young women from all around the country vying for one of the coveted eighteen spots on the swimming and diving team, plus six alternates, more than three times the number of entrants who competed for a place on the 1920 squad. What she had done in the past didn't matter—now she had to perform.

In early June Trudy and most of the other girls gathered at the site of the trials, the Briarcliff Lodge, a hotel and resort in Briarcliff Manor, New York, in Westchester County, just north of New York City. The resort, which offered to host the trials in exchange for the publicity, featured an outdoor pool. On June 7 and 8 the women would swim a series of trials to determine the makeup of the team for the full compliment of Olympic events open to them: the 400-meter relay, 400-meter freestyle, 200-meter breaststroke, 100-meter freestyle, 100-meter backstroke, and both platform and springboard diving. The

Times

accurately referred to the group, which included swimmers from as far off as Hawaii, as "the greatest aggregation of girl swimmers ever."

When the Trudy awoke on the morning of June 7, it was raining. Those conditions brought a smile to her eyes, and at breakfast, while other competitors looked glumly out the rain-smeared windows at the downpour, Trudy bubbled with confidence and nervous energy. She loved the rain, absolutely loved it, for over the past few years, beginning with the Day Cup, rain had always been a portent of good fortune, and many of her greatest victories had come during a deluge. Had she been a thoroughbred racehorse she would have been known as a "mudder," one whose performance improved in adverse weather. Both the weather and the outdoor pool in Briarcliff played to her strength.

There was pressure on Trudy to win, and not just because she was expected to. While a top two or three finish was generally thought to be good enough to make the team, one never knew for sure. Funds were tight, and while the trials were being held, the AOC was meeting in New York to discuss Olympic financing. Expenses for the

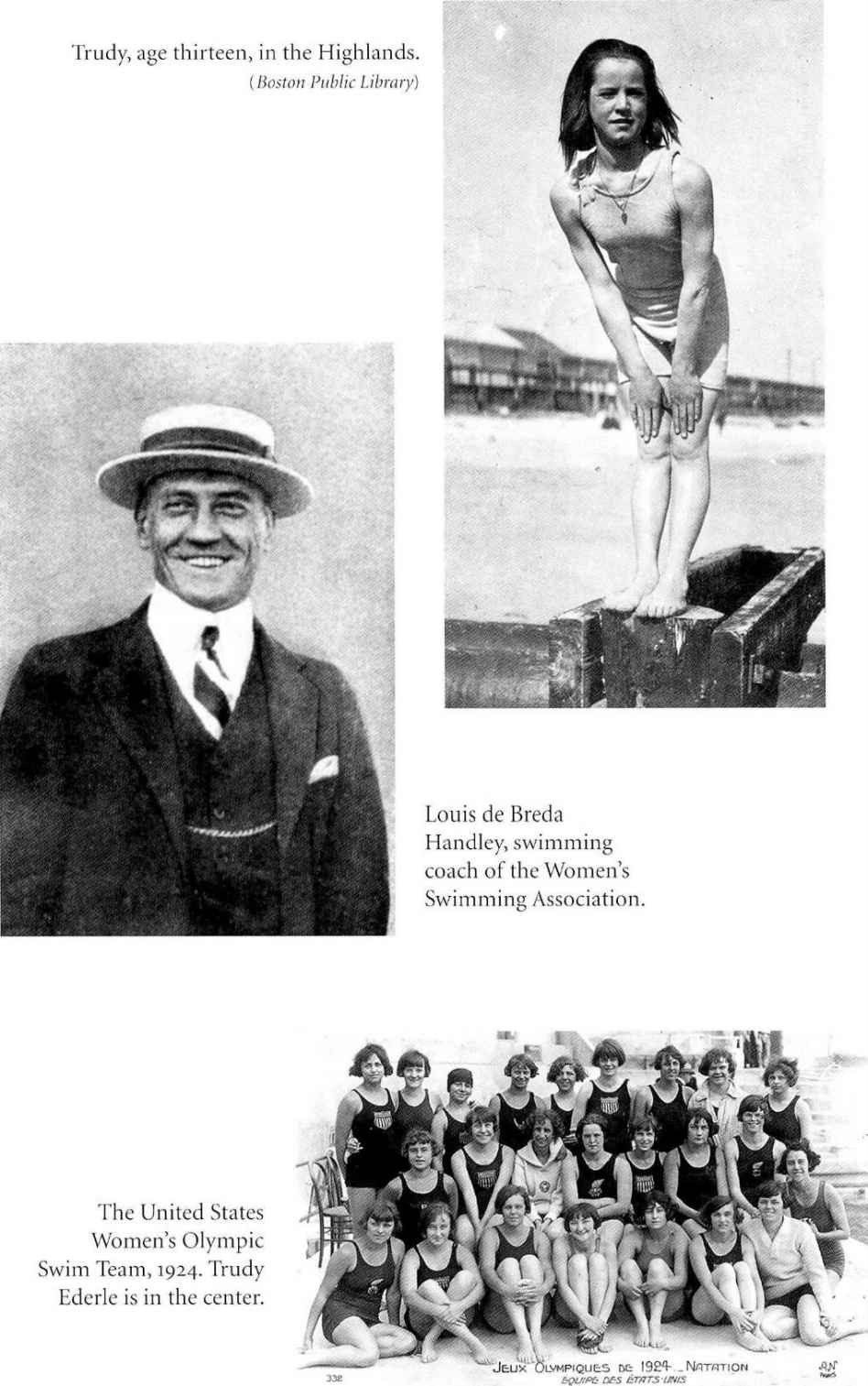

Trudy, age thirteen, in the Highlands.

(Boston Public Library)

Louis de Breda Handley, swimming coach of the Women's Swimming Association.

The United States Women's Olympic Swim Team, 1924. Trudy Ederle is in the center.

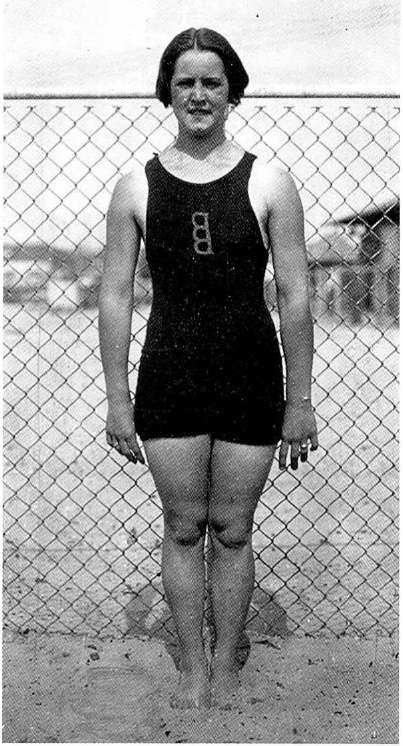

Trudy, age eighteen, 1925, just before making her first attempt to swim the English Channel.

(Boston Public Library)

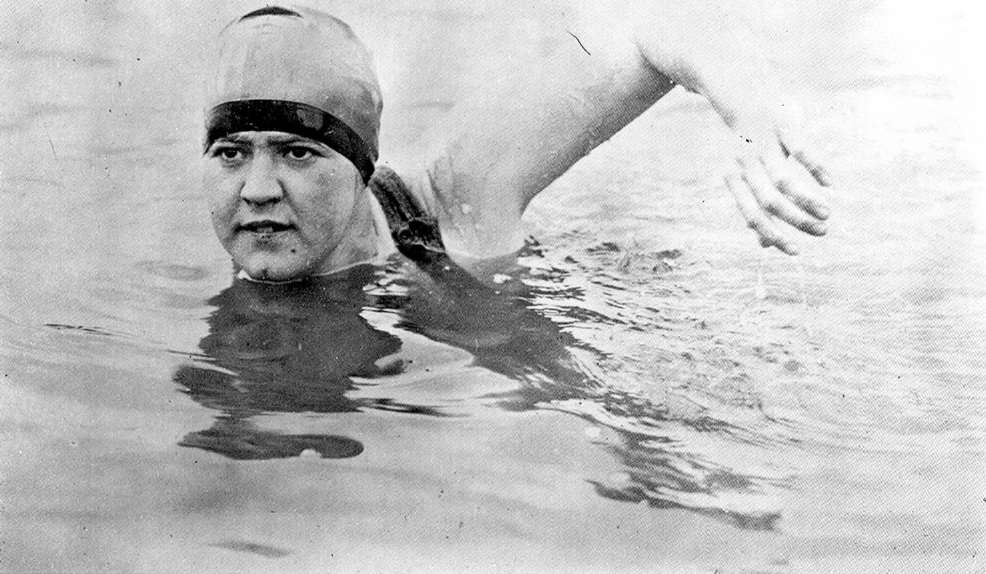

Trudy Ederle, training to swim the Channel. (

Library of Congress)

Trudy Ederle signing her contract with the

News-Tribune

syndicate, flanked by Dudley Field Malone (left) and her father (standing, right).

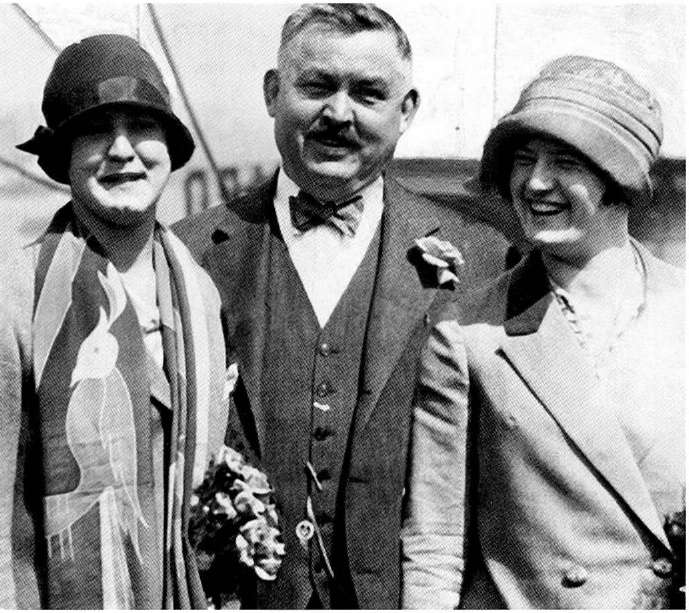

Trudy (left), her father, and her sister Meg (right), aboard the

Berengaria

just before leaving for France, 1926.

(Boston Public Library)