With Love and Quiches (6 page)

Read With Love and Quiches Online

Authors: Susan Axelrod

Marvin introduced me to the manager of O’Neals’ Baloon, a highly visible establishment across from Lincoln Center, and I was able to convince him to try my quiche as a lunch special to be served with salad. It proved so popular that it went onto the regular menu.

The rest is pretty much history. Pub after pub tried out our quiche and started ordering from us. Restaurant managers all over the city

shared their ideas, and Bonne Femme picked up many more accounts, all by word of mouth.

I was running all over the city hawking my wares, and almost everywhere I went, the restaurant manager would try out our quiche. We were still the only quiche company around, so we had a head start before the field became crowded. This was between 1973 and 1974, a recessionary period during which you could shoot a cannon through a white tablecloth restaurant and not hit anybody. We, of course, did not invent the quiche, but we started the trend that popularized it as pub food. Jill and I began to realize that thanks to Marvin’s introductions and the relative novelty of our product, Bonne Femme had a tiger by the tail.

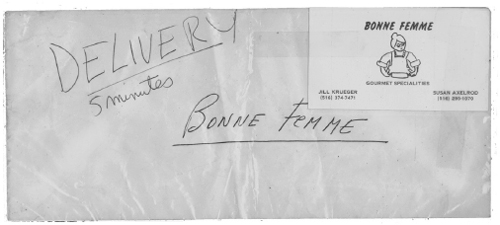

We were still operating entirely out of my garage, and I was still delivering in my car, driving as fast as I dared, my trunk still stuffed with newspaper (my secret insulating material). I was making sales calls between deliveries, up Third Avenue and down Second. I had this ridiculous paper sign reading “

DELIVERY—5 minutes—BONNE FEMME

” that I would put on the windshield of my Chevy. All the police in the city must have been scratching their heads—“Who

is

this crazy lady?” But I never got a ticket, not even once!

The success of our quiche in restaurants across the city marked the beginning of the end of the Keystone Kops Quiche Factory. By now

we had fifty or more accounts between New York City and Nassau County, where we started. We found ourselves out of space again, with no place to keep our finished inventory, so we started stashing it in our friends’ freezers all over the neighborhood—a logistical nightmare.

Our fame was growing, and I was on the road at least three days a week. At this point Jill and I were definitely defining our roles and dividing the labor. And it looked as if we would reach almost $65,000 in sales by the end of our second year, maybe even $75,000.

I smile to myself when I recall the names of our original accounts, some of which are still going strong and have become icons in the city; others that are now known nationally and internationally, with many hundreds or thousands of units. More and more restaurants were trying out the quiche and our desserts. I already mentioned O’Neals’ Baloon, which was owned by my new friend Michael O’Neal and his late brother, the actor Patrick O’Neal; there was Charlie’s, P.J. Clarke’s, J. G. Melon, the Wicked Wolf, Puffing Billy, Proof of the Pudding, the Grand Central Oyster Bar, and the iconic Copacabana nightclub. Another was the Peartrees, owned by Michael “Buzzy” O’Keeffe, who went on to open the River Café, today considered one of the finest restaurants in the country.

And then there was T.G.I. Friday’s, long before it was sold and became the omnipresent global chain it is today. Besides Friday’s there was also a Tuesday’s and a Thursday’s, also owned by Alan Stillman, as he began his long career as a successful restaurateur. I remember the delivery to Thursday’s was really frightening, located as it was in the bowels of a building on 58th Street with dark, endless corridors that never ceased to scare the daylights out of me. I also remember with a smile that the manager of Friday’s told me he always kept one of my pecan pies at home on top of his refrigerator; every night when he got home at three or four in the morning, he rewarded himself with a slice before falling into bed.

Our packaging was still quite rudimentary. We did not yet have boxes in which to pack our products since we simply would have had no place

to store them. So we were still using plastic bags—and, I am embarrassed to admit, in some cases tinfoil. How I carried them into the restaurants I cannot imagine, but I am quite sure it must have made me look pretty foolish and unprofessional, which I, most definitely, still was.

During the process of our initial expansion, I learned one of my very big lessons in business. We were selling our newest product, a Chocolate Mixed Nut Pie, to a restaurant called Gertrude’s on East 64th Street. It was one of those restaurants that was very hot—all the celebrities and beautiful people flocked there almost before the expression “beautiful people” existed. I got a call from Gertrude at one in the morning telling me she needed four more pies right away.

“Gertrude, do you realize what time it is?” I asked wearily.

“

You have to

, Susan!” she said. Of course, she was right, and it only took me a moment to realize it. Even back then I began to understand that customer service is as important as the product. I dragged myself out of bed, packed up the pies, and began the hour-long drive to Gertrude’s.

By then I was getting some help with my deliveries; hardly anyone in our neighborhood left for the city without making a delivery—even people we hardly knew, friends of our friends.

We still had no real profits, but our reputation was growing, a fact that began causing problems. It got to the point where we had lots of retail customers driving up to the house to stock up on our products, and large delivery trucks were pulling into the driveway to bring us ingredients all week long. Once again, desperate for space, we also began a slow creep back into the house—back through the kitchen and into the dining room, the library, the sun porch.

Our neighbors were proud of us, and very protective, but the village was another story. We lived in an exclusive residential community, and finally we got the letter I had figured would show up eventually. In not-so-polite language, it suggested that the village thought it was time for Bonne Femme to move its operations elsewhere.

The next leg of our journey was about to begin.

Becoming Love and Quiches (1974)

I didn’t fail the test; I just found a hundred ways to do it wrong.

—Benjamin Franklin

W

ith pressure from the village to move our burgeoning business elsewhere, we started to look for our first real space. We wanted a small building close to home, preferably somewhere our children could walk to after school and help us out. It had been just a little over a year since Bonne Femme got off the ground as not much more than a whim, but by April of 1974, we had located our first little shop.

The place we found was on Franklin Avenue in Hewlett, a small street across from the local firehouse and next to the train station. It was six hundred square feet of space, plus a big basement, and it was less than five minutes from where we both lived. Plus, the rent was only a few hundred dollars a month. To us it was pure paradise!

We actually had a little business going. We had a good starting base of customers, we had all of the New York metropolitan area open to us, and we were excited to see where we could take it. Jill already had a few misgivings—the amount and scope of work we were putting in was a bit more than she had bargained for—but I did not. I was all in.

Since we didn’t want to sign the lease personally, we went to incorporate under the name Bonne Femme. Much to our dismay, the name was already being used by a beauty shop; as a result, our application was automatically turned down by New York State. We needed to think of another name—fast. Jill’s aunt had bought us a gift of something she had run across in an antique shop; it was a framed embroidery sampler simply saying “Love and Quiches” in a lovely script. As a joke, and because we had to act very quickly, we decided to incorporate under the name Love and Quiches. We actually loved the name, so that was that. (We also recognized that this was a great name, and so we trademarked Love and Quiches in June 1976 when the company really started to grow.

*

) Jill and I each invested $6,000 to outfit the store. That might not seem like much, but it’s amazing just how much you could buy for $12,000 in 1974. We certainly could have used more equipment, but what we already had would have to do for the moment. We designed the place on a scrap of paper, just like we kept our books, but we now had a little front office and retail space, a decently sized work space with a seven-by-eleven-foot walk-in freezer, a second Blodgett convection oven, a second big double-door Traulsen fridge, a small scullery, and storage space. We brought our pie press machine with us from the garage, and though I can’t swear to it, there is a good chance that secondhand machine is still in use for small runs at our plant to this very day. We also bought two forty-quart Hobart mixers to complement the two twenty-quart mixers we brought with us from the garage.

We decorated the front office by ourselves—even sewed up the curtains—but I must admit that our effort was pretty feeble, with no real style. Not exactly high end, but at the time we were very happy.

Some of the first visitors to our new shop were the firemen from across the street asking if they could get some “quickies.” After a few bewildered moments, Jill and I realized what they meant.

Quiche

was not exactly a household word at the time, so there is the possibility that they were serious and not being snide. As we started getting our first walk-in buyers, mostly commuters on their way to or from the nearby train station, we picked up some other comical pronunciations; my favorite was the customer who kept coming back to get some more of our delicious “qui-SHAYS.” We also sold “kwishes” and “knishes”!

In the shop we had only one desk, which Jill and I shared, but at first we had it facing the wall, with our backs to all the action. We sensed our error, and with one quick turn, a whole new world opened up! Now we could keep an eye on everything while we worked. Next, my father insisted that we buy an adding machine

with

a tape; without it, I always had to add everything twice to make sure of the numbers. Of course I resisted, like I resisted all of his advice, but he won that round, and my accounting work was cut in half. This was long before the age when computers came into universal use. Businesses at the time used the general ledger to keep their books. But we hadn’t even gotten

that

far yet.

What remains a mystery is how we kept it all going. Though business with our restaurant customers was brisk, we still had no clue how to price our products properly, there was no profit, and a salary for each of us was out of the question. Every penny went to keep Love and Quiches afloat. Regardless, our little start-up seemed to take on a life of its own and we grew. What we should have invested in was some solid professional advice, but that never occurred to us. We just kept baking, and I continued to run up and down the streets of Manhattan collecting more customers for our quiches, pies, and cheesecakes.

Encouraged by my taking his advice about the adding machine, my amazed and proud father started hanging around almost nonstop as

my accidental business developed. One day he would suggest we concentrate on only a few products, and then the next day he would come in with a huge folder spilling over with articles, recipes—everything from muffins to raspberry cakes to pizza—and new product ideas. He was disruptive and sometimes a nuisance, but welcome anytime.

Now that we were out of the garage, I wasn’t living over the store, and we were able to keep all of our inventory under one roof rather than having it dispersed all over the neighborhood—much easier to keep track of. But it was getting to be too much to deliver out of the trunk of my Chevy. It was exhausting, and because the number of stops I had to make was growing, delivering product to our customers without everything softening around the edges was becoming much too tricky. While newspaper worked just fine as an insulator when I had very few stops to make, it was only taking me so far.

Serendipity intervened. We bought all of our new equipment from the same supplier that we had used in the garage, and we recognized the young man who made the deliveries to our new shop. When Jill and I reminded him this was his second time around with us, his eyes got very wide, and he called and quit his job on the spot! Now it was

we

who were wide-eyed as he turned to us and asked for a job, explaining that he had a personal policy of not staying at any job for more than a year. The timing was perfect; Jill and I had been talking about hiring a driver. We hired Don, and soon after hurried out to buy our first truck! (Don ended up disobeying his own rule: he worked for me for

many

years, and he became plant manager just over two years after we hired him.)

We equipped Don with a secondhand truck from Avis. It was a well-used, slightly banged-up silver refrigerated van we dubbed the “Silver Bullet.” With our first driver, I could expand my sales arena to include Greenwich Village and further downtown Manhattan, as well as Brooklyn and Queens.

Thanks to our young accountant, we kept simple but real books. One of our friends became our part-time bookkeeper. We had two other production workers to help with packing, cleanup, and the like, but Jill and I still did all the product development, mixing, and baking ourselves.