With Liberty and Justice for Some (10 page)

Read With Liberty and Justice for Some Online

Authors: Glenn Greenwald

Unsurprisingly, Murray’s former boss, Representative Cramer, was one of twenty-one Blue Dogs who wrote to Pelosi demanding immunity for Murray’s client, Comcast, along with the rest of the nation’s telecoms.

The Quinn Gillespie firm, mentioned in the article as the home of a former aide to Blue Dog representative Tim Holden, was also active in the telecom fray: it received $60,000 from AT&T in the first quarter of 2008 and more than $300,000 in 2007. And it is no coincidence that Holden was also one of the twenty-one Blue Dogs writing to Pelosi to promote amnesty for the client of his former top aide.

The list goes on and on. In the first three months of 2008 alone, for example, AT&T paid $200,000 to Roberti Associates, a small lobbying firm led by Vincent Roberti, a former Democratic congressman and current member of the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee’s finance group. The firm’s managing partner is Harmony Knutson, who had been a finance director for the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee and for Democratic senator Kent Conrad, among many others. One could spend all day documenting the large sums paid by immunity-seeking telecoms to lobbying firms stuffed with former executive officials and key congressional staffers from both political parties.

This kind of spending, of course, is what leads to having major corporations literally write our nation’s laws, and what made it possible for the telecoms to demand from Congress such an extraordinary and transparently corrupt gift as retroactive immunity for blatant lawbreaking. A

Politico

article published during the immunity debate shed light on the sleazy and corrupt process.

Telecom companies have presented congressional Democrats with a set of proposals on how to provide immunity to the businesses that participated in a controversial government electronic surveillance program, a House Democratic aide said Wednesday….

Although it remains to be seen if congressional Democrats will accept the telecom companies’ proposal, the communication between the two sides signifies that progress is being made.

The “two sides” mentioned here are the House Democratic leadership and the telecoms. In other words, congressional leaders were “negotiating” with the telecoms—the defendants in pending lawsuits—on the best way of immunizing them from liability, no doubt with the help of the former Democratic members and staffers being paid by the telecoms to speak to their ex-bosses and colleagues about what they should do. This banana-republic-like corruption is generally how our laws are written today.

And on top of that multimillion-dollar lobbying assault came many thousands more in campaign contributions—money that the telecoms poured directly into the coffers of members of Congress in order to purchase amnesty for their lawbreaking. One prime target of the telecoms’ legalized bribery was Democratic senator Jay Rockefeller, who had become chairman of the Senate Intelligence Committee when Democrats won control of Congress in 2006 and was thus the linchpin for securing the immunity they sought.

Back in 2003, Rockefeller had been one of the tiny handful of senators who were informed by the Bush administration about the warrantless spying on Americans. At the time, he did nothing other than send a short, meaningless handwritten letter to Dick Cheney expressing “concerns.” But his concerns—along with the anger he had publicly expressed regarding his inability to learn anything about the spying program—quickly evaporated. Indeed, by the fall of 2007 Rockefeller emerged as the most vocal congressional advocate for full telecom immunity; as the

New York Times

reported, he jointly created a proposal for such immunity directly with Dick Cheney. With the Bush White House and Director of National Intelligence McConnell already fully on board, the telecoms’ ability to secure the support of the key Democratic senator on intelligence issues was a major coup.

The reason for their success is not difficult to understand. In October 2007,

Wired

wrote an article about Rockefeller titled “Democratic Lawmaker Pushing Immunity Is Newly Flush With Telco Cash.” It documented that as Rockefeller was “steering the secretive Senate Intelligence Committee to give retroactive immunity to telecoms that helped the government secretly spy on Americans,” he was the recipient of a substantial increase in telecom money. If he wanted to stay in the Senate, Rockefeller was required to run for reelection in 2008, and the

Wired

article, using public finance records, detailed how much assistance the telecom industry was suddenly providing.

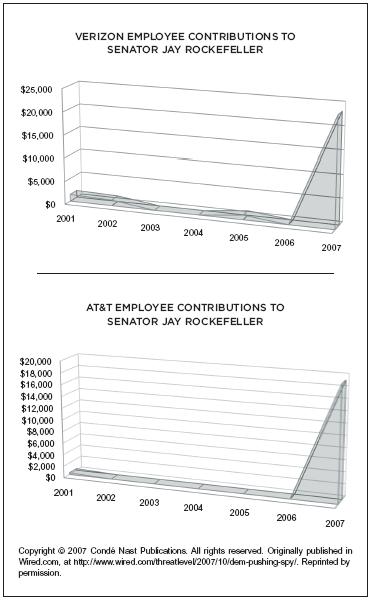

Top Verizon executives, including CEO Ivan Seidenberg and President Dennis Strigl, wrote personal checks to Rockefeller totaling $23,500 in March, 2007. Prior to that apparently coordinated flurry of 29 donations, only one of those executives had ever donated to Rockefeller (at least while working for Verizon).

In fact, prior to 2007, contributions to Rockefeller from company executives at AT&T and Verizon were mostly nonexistent.

But that changed around the same time that the companies began lobbying Congress to grant them retroactive immunity from lawsuits seeking billions for their alleged participation in secret, warrantless surveillance programs that targeted Americans.

The Spring ’07 checks represent 86 percent of money donated to Rockefeller by Verizon employees since at least 2001.

AT&T executives discovered a fondness for Rockefeller just a month after Verizon execs did and over a three-month span, collectively made donations totaling $19,350.

AT&T Vice President Fred McCallum began the giving spree in May with a $500 donation. 22 other AT&T high fliers soon followed with their own checks.

Wired

included

two charts

to illustrate the telecom industry’s sudden fondness for Rockefeller.

The significance of these donations extends far beyond mere money. To be sure, the money matters. Although Jay Rockefeller lives off a vast family fortune, after he was first elected to the Senate—which he accomplished by flooding his small West Virginia state with $12 million of his own money—Rockefeller vowed that he would never again spend personal funds on a political race. Like most other politicians, then, Rockefeller relies upon donors to maintain his political power.

But beyond that, these endless interactions between senators and the executives, lawyers, and lobbyists for large corporations also create a culture, a community, that is closed to those who cannot afford the admission fee—namely, the vast majority of Americans. With donations comes access; after AT&T and Verizon delivered large checks to Senator Rockefeller, for example, they were able to hold a cocktail party attended by numerous key Democrats. Similarly, lobbyists are almost always former officials in Congress or the executive branch and thus friends of those who are still in political office. Soon enough, lawmakers find themselves spending most of their time with representatives of the corporations that fund their careers and that have the power to end them. Such communion only further accelerates the intermingling of government and private industry. The /files/04/29/07/f042907/public/private merger exists not only on the tangible levels of policy and money but on intangible—though equally potent—social, cultural, and socioeconomic levels as well.

Providing crucial support to this army of corporations and lobbyists was, as usual, the establishment media. In 2008, the vast majority of establishment journalists emphatically advocated for telecom immunity. The self-proclaimed watchdogs over power thereby yet again devoted themselves to suppressing facts, quashing investigations, and demanding protection for elites from all accountability. They did so by invoking the same batch of clichés now hauled out every time elite immunity is to be sold to the public.

The

Washington Post

’s David Ignatius casually proclaimed, as though it were the most natural thing in the world: “A key administration demand is retroactive immunity for telecommunications companies that agreed to help the government in what they thought was a legal program. That seems fair enough.”

Time

’s Joe Klein cast the telecoms as the victims in need of protection: “I have no problem with telecommunications companies being protected from lawsuits brought by those who may or may not have been illegally targeted simply because the Bush Administration refused to update the law.” The

Washington Post

editorial page repeatedly urged the granting of immunity, claiming—in perfect lockstep with McConnell and other Bush officials—that telecoms could not afford the liability to which they would be subjected, that their cooperation was urgently needed to keep us safe from terrorists, and that it was terribly unfair to punish them for having unquestioningly complied with the president’s requests (“the telecommunications providers seem to us to have been acting as patriotic corporate citizens in a difficult and uncharted environment”).

Perhaps most tellingly, the

Washington Post

editorial page actually argued that it was unfair to subject telecoms to the “high costs” of defending against these lawsuits—meaning their attorneys’ fees. In October 2007, they demanded amnesty, arguing, “We do not believe that these companies should be held hostage to costly litigation in what is essentially a complaint about administration activities.”

In 2007, the total revenue of Verizon was $93 billion. AT&T’s total 2007 revenue was $119 billion, which gave it after-tax income of $12 billion. The costs of paying their attorneys to defend a few lawsuits was a minuscule—really undetectable—amount to these companies. Whatever the telecoms’ motives were in desperately seeking amnesty for their lawbreaking, being relieved from “costly litigation” had nothing to do with it.

(Notably, this sort of populist rhetoric about the “high costs” of litigation is actually valid when it comes to lawsuits against small businesses or individuals. There, attorneys’ fees and other expenses really do make lawsuits expensive to defend—often prohibitively so. But no matter; individuals of modest means and small businesses, when sued, still have to go to court to prove they did nothing wrong; they don’t have Congress intervene to shield them.)

The customers’ lawsuits would have proved “costly” to the telecoms only if they were found to have knowingly and deliberately broken the law—in which case the penalties would have been fully deserved. But so complete is the identification of journalists such as those who write

Post

editorials with the nation’s most powerful that they indignantly demanded that the telecoms—among the wealthiest corporations in the world—be shielded by a special act of Congress in order to spare them the burdens of “costly litigation.” That such deep concern was expressed for the extraordinarily profitable telecoms as they battled the under-funded, tiny nonprofit groups representing ordinary Americans highlighted the exclusive fixation on the interests of elites by much of our media class.

The

Post

also misled its readers when it characterized the lawsuits as nothing more than “a complaint about administration activities.” In fact, the lawsuits alleged that the telecoms had violated multiple federal laws—laws enacted as a result of the discoveries by the Church Commission of massive invasions of the privacy rights of American citizens and decades-long abuses of surveillance powers by the government. Corporations do not have license to break the law because the president tells them to. It is truly unbelievable that this even needs to be pointed out at all.

The lawsuits against the telecoms were the sole hope for obtaining a judicial ruling on whether the spying was illegal and for bringing about a minimum amount of disclosure and accountability. But as always happens when the interests of financial and political elites are in play, journalists helped lead the chorus in demanding that all such proceedings be quashed.

The Unstoppable Machine of Elite Lawlessness

Once it became clear in the fall of 2007 that the White House was seriously demanding retroactive amnesty for the telecoms and that congressional Democrats were preparing to grant it, a coordinated and sustained public campaign was launched—largely via the Internet—to oppose telecom immunity.

In October, as the Democratic presidential primary was heating up, various blogs organized a mass call-in campaign to insist that each candidate clearly state his or her position on telecom immunity and vow to do everything possible to oppose it. In response, all of the major Democratic candidates issued statements vehemently opposing amnesty for the telecoms, and Barack Obama went even farther, vowing to filibuster any bill containing such immunity. Obama’s campaign spokesman, Bill Burton, put the promise in a way that could not have been more absolute: “To be clear, Barack will support a filibuster of any bill that includes retroactive immunity for telecommunications companies.”