Why People Believe Weird Things: Pseudoscience, Superstition, and Other Confusions of Our Time (52 page)

Authors: Michael Shermer

Tags: #Creative Ability, #Parapsychology, #Psychology, #Epistemology, #Philosophy & Social Aspects, #Science, #Philosophy, #Creative ability in science, #Skepticism, #Truthfulness and falsehood, #Pseudoscience, #Body; Mind & Spirit, #Belief and doubt, #General, #Parapsychology and science

2. Gender and Belief

In many ways the orthogonal relationship of intelligence and belief is not unlike that of gender and belief. With the surge of popularity of psychic mediums like John Edward, James Van Praagh, and Sylvia Browne, it has become obvious to observers, particularly among journalists assigned to cover them, that at any given group gathering (usually at large hotel conference rooms holding several hundred people, each of whom paid several hundred dollars to be there), the vast majority (at least 75 percent) are women. Understandably, journalists inquire whether women, therefore, are more superstitious or less rational than men, who typically disdain such mediums and scoff at the notion of talking to the dead. Indeed, a number of studies have found that women hold more superstitious beliefs and accept more paranormal phenomena as real than men. In one study of 132 men and women in New York City, for example, scientists found that more women than men believed that knocking on wood or walking under a ladder brought bad luck (Blum and Blum 1974). Another study showed that more college women than men professed belief in precognition (Tobacyk and Milford 1983).

Although the general conclusion from such studies seems compelling, it is wrong. The problem here is with limited sampling. If you attend any meeting of creationists, Holocaust "revisionists," or UFOlogists, for instance, you will find almost no women at all (the few that I see at such conferences are the spouses of attending members and, for the most part, they look bored out of their skulls). For a variety of reasons related to the subject matter and style of reasoning, creationism, revisionism, and UFOlogy are guy beliefs. So, while gender is related to the target of one's beliefs, it appears to be unrelated to the process of believing. In fact, in the same study that found more women than men believe in precognition, it turned out that more men than women believe in Big Foot and the Loch Ness monster. Seeing into the future is a woman's thing, tracking down chimerical monsters is a man's thing. There are no differences between men and women in the power of belief, only in what they choose to believe.

3. Age and Belief

The relationship between age and belief is also mixed. Some studies, such as a 1990 Gallup poll indicating that people under thirty were more superstitious than older age groups, show that older people are more skeptical than younger people

(

http://www.gallup.com/poll/releases/pr010608.asp

)

. Another study showed that younger police officers were more likely to believe in the full-moon effect (where allegedly crime rates are higher during full moons) than older police officers. Other studies are less clear about the relationship. British folklorist Gillian Bennett (1987) discovered that older retired English women were more likely to believe in premonition than younger women. Psychologist Seymour Epstein (1993) surveyed three different age groups (9-12, 18-22, 27-65) and discovered that the percentage of belief in each age division depended on the specific phenomena under question. For telepathy and precognition there were no age group differences. For good luck charms more older adults said they had one than did college students or children. The belief that wishing something to happen will make it so decreased steadily with age (Vyse 1997). Finally, Frank Sulloway and I found that religiosity and belief in God steadily decreased with age, until about age seventy-five, when it went back up (Shermer and Sulloway, in press).

These mixed results are due to what is known as person-by-situation effects, where a simple linear causal relationship between two variables rarely exists. Instead, to the question "does X cause Y?" the answer is often "it depends." Bennett, for example, concluded that the older women in her study had lost power, status, and especially loved ones, for which belief in the supernatural helped them recover. Sulloway and I concluded in our study that age and religiosity vary according to one's situation in relation to both early powerful influences and the later perceived impending end of life.

4. Education and Belief

Studies on the relationship between education and belief are, like intelligence, gender, and age, mixed. Psychologist Chris Brand (1981), for example, discovered a powerful inverse correlation of -.50 between IQ and authoritarianism (as IQ increases authoritarianism decreases). Brand concluded that authoritarians are characterized not by an affection for authority, but by "some simple-minded way in which the world has been divided up for them." In this case, authoritarianism was being expressed through prejudice by dividing the world up by race, gender, and age. Brand attributes the correlation to "crystallized intelligence," a relatively flexible form of intelligence shaped by education and life experience. But Brand is quick to point out that only when this type of intelligence is modified by a liberal education does one see a sharp decrease in authoritarianism. In other words, it is not so much that smart people are less prejudiced and authoritarian, but that educated people are less so.

Psychologists S. H. and L. H. Blum (1974) found a negative correlation between education and superstition (as education increased superstitious beliefs decreased). Laura Otis and James Alcock (1982) showed that college professors are more skeptical than either college students or the general public (with the latter two groups showing no difference in belief), but that within college professors there was variation in the types of beliefs held, with English professors more likely to believe in ghosts, ESP, and fortune-telling. Another study (Pasachoff et al. 1971) found, not surprisingly, that natural and social scientists were more skeptical than their colleagues in the arts and humanities; most appropriately, in this context, psychologists were the most skeptical of all (perhaps because they best understand the psychology of belief and how easy it is to be fooled).

Finally, Richard Walker, Steven Hoekstra, and Rodney Vogl (2001) discovered that there was no relationship between science education and belief in the paranormal among three groups of science students at three different colleges. That is, "having a strong scientific knowledge base is not enough to insulate a person against irrational beliefs. Students that scored well on these tests were no more or less skeptical of pseudoscientific claims than students that scored very poorly. Apparently, the students were not able to apply their scientific knowledge to evaluate these pseudo-scientific claims. We suggest that this inability stems in part from the way that science is traditionally presented to students: Students are taught what to think but not how to think."

Whether teaching students how to think will attenuate belief in the paranormal remains to be seen. Supposedly this is what the critical thinking movement has been emphasizing for three decades now, yet polls show that paranormal beliefs continue to rise. A June 8, 2001, Gallup Poll, for example, reported a significant increase in belief in a number of paranormal phenomena since 1990, including haunted houses, ghosts, witches, communicating with the dead, psychic or spiritual healing, that extraterrestrial beings have visited earth, and clairvoyance. In support of my claim that the effects of gender, age, and education show content dependent effects, the Gallup poll found:

Gender:

Women are slightly more likely than men to believe in ghosts and that people can communicate with the dead. Men, on the other hand, are more likely than women to believe in only one of the dimensions tested: that extraterrestrials have visited earth at some point in the past.

Age:

Younger Americans—those 18 to 29—are much more likely than those who are older to believe in haunted houses, in witches, in ghosts, that extraterrestrials have visited earth, and in clairvoyance. There is little significant difference in belief in the other items by age group. Those 30 and older are somewhat more likely to believe in possession by the devil than are the younger group.

Education:

Americans with the highest levels of education are more likely than others to believe in the power of the mind to heal the body. On the other hand, belief in three of the phenomena tested goes up as the educational level of the respondent goes down: possession by the devil, astrology and haunted houses.

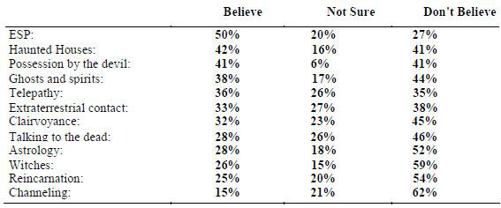

Additional results from the survey included:

An even more striking poll result was reported by Gallup on March 5, 2001, about the surprising lack of belief in and understanding of the theory of evolution. Specifically, of those Americans polled:

45% agreed with the statement: "God created human beings pretty much in their present form at one time within the last 10,000 years or so."

37% agreed with the statement: "Human beings have developed over millions of years from less advanced forms of life, but God guided this process."

12% agreed with the statement: "Human beings have developed over millions of years from less advanced forms of life, but God had no part in this process."

Despite enormous funds and efforts allocated toward the teaching of evolution in public schools, and the proliferation of documentaries, books, and magazines presenting the theory on all levels, Americans have not noticeably changed their opinion on this question since Gallup started asking it in 1982. Gallup did find that individuals with more education and people with higher incomes are more likely to think that evidence supports the theory of evolution, and that younger people are also more likely than older people to think that evidence supports Darwin's theory (again confounding the age variable). Nevertheless, only 34 percent of Americans consider themselves to be "very informed" about the theory of evolution, while a slightly greater percentage—40 percent—consider themselves to be "very informed" about the theory of creation. Younger people, people with more education, and people with higher incomes are more likely to say they are very informed about both theories.

5. Personality and Belief

Clearly, human thought and behavior are complex and thus studies such as those reported above rarely show simple and consistent findings. Studies on the causes and effects of mystical experiences, for example, show mixed findings. The religious scholar Andrew Greeley (1975), and others (Hay and Morisy, 1978), have found a slight but significant tendency for mystical experiences to increase with age, education, and income, but there were no gender differences. J. S. Levin (1993), by contrast, in analyzing the 1988 General Social Survey data, found no significant age trends in mystical experiences.

But within any group, as defined by intelligence, gender, age, or education, are there any personality characteristics related to belief or disbelief in weird things? First, we note that personality is best characterized by traits, or relatively stable dispositions. The assumption is that these traits, in being "relatively stable," are not provisional states, or conditions of the environment, the altering of which changes the personality. Today's most popular trait theory is what is known as the Five Factor model, or the "Big Five": (1) Conscientiousness (competence, order, dutifulness), (2) Agree-ableness (trust, altruism, modesty), (3) Openness to Experience (fantasy, feelings, values), (4) Extroversion (gregariousness, assertiveness, excitement seeking), and (5) Neuroticism (anxiety, anger, depression). In the study on religiosity and belief in God Frank Sulloway and I conducted, we found openness to experience to be the most significant predictor, with higher levels of openness related to lower levels of religiosity and belief in God. In studies of individual scientists' personalities and their receptivity to fringe ideas like the paranormal, I found that a healthy balance between high conscientiousness and high openness to experience led to a moderate amount of skepticism. This was most clearly expressed in the careers of paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould and astronomer Carl Sagan (Shermer, in press). They were nearly off the scale in both conscientiousness and openness to experience, giving them that balance between being open-minded enough to accept the occasional extraordinary claim that turns out to be right, but not so open that one blindly accepts every crazy claim that anyone makes. Sagan, for example, was open to the search for extraterrestrial intelligence which, at the time, was considered a moderately heretical idea; but he was too conscientious to accept the even more controversial claim that UFOs and aliens have actually landed on earth (Shermer 2001).

The psychologist David Wulff (2000), in a general survey of the literature on the psychology of mystical experiences (a subset of weird things), concluded that there were some consistent personality differences:

Persons who tend to score high on mysticism scales tend also to score high on such variables as complexity, openness to new experience, breadth of interests, innovation, tolerance of ambiguity, and creative personality. Furthermore, they are likely to score high on measures of hypnotizability, absorption, and fantasy proneness, suggesting a capacity to suspend the judging process that distinguishes imaginings and real events and to commit their mental resources to representing the imaginal object as vividly as possible. Individuals high on hypnotic susceptibility are also more likely to report having undergone religious conversion, which for them is primarily an experiential rather than a cognitive phenomenon—that is, one marked by notable alterations in perceptual, affective, and ideomotor response patterns.