Why Do Pirates Love Parrots? (16 page)

Read Why Do Pirates Love Parrots? Online

Authors: David Feldman

Sways with a wiggle, with a wiggle when she walks

Sways with a wiggle when she walks…

“What is love? Five feet of heaven in a ponytail

The cutest ponytail that sways with a wiggle when she walks…

“What Is Love,” words and music by Les Pockriss and Paul J. Vance

A

s the effect of the female sway upon men dates back long before the paean above (which was a big hit for a group called the Playmates in 1959), we’d always assumed that women swayed with intention and premeditation. So we were surprised when this Imponderable was submitted by a female. As anyone who watches

America’s Next Top Model

can attest, swaying can be taught. But as we have learned, it can also be a naturally occurring phenomenon.

Scientists have pondered the female hip sway, and all the experts we consulted agree that there are anatomical and biomechanical reasons why women’s hips sway more than men when they are walking. For one, women’s pelvises tilt more when their legs are moving. According to John F. Hertner, professor of biology at the University of Nebraska at Kearney, the tilting is caused by three factors:

- 1.

The female pelvis is relatively wide; in comparison, the male’s is taller and narrower. - 2.

In women, the socket of the pelvis, which accepts the femur (upper leg bone), faces a bit more toward the front than the male pelvis. - 3.

The outward flare of the iliac crest, the upper, protruding bone in the pelvis, is greater in women than men.

Tom Purvis, a registered physical therapist and cofounder of the Resistance Training Specialist program, feels that these differences play out in practice. In Purvis’s opinion, there is a purely biomechanical explanation for women’s hip sway. According to Purvis, it is always more efficient and stable to support movements in the direct line of our center of gravity. If all that were necessary to walk efficiently was the even distribution of weight, it would make more sense for us to walk like tightrope walkers, placing one foot directly in front of the other.

But in practice, we don’t walk this way, because two little things (or in some cases big things) get in our way—our hips. If you walk like a tightrope walker, you have to lift each foot up and move it around your body to get to the “rope”—it is time-consuming and awkward. But even if you look foolish “walking the line,” your hips won’t sway.

You could also choose to walk with your legs farther apart, directly beneath each hip. The result? Your entire body weight would shift from foot to foot, causing your whole body to sway from side to side. It’s a cute way to locomote—penguins have been attracting other penguins by moving like this since waddling began. But for some strange reason, humans don’t see waddling as being as sexy as swaying.

Most humans compromise by walking with the legs less far apart, and moving their centers of gravity, the hips, laterally over each foot when walking. Purvis concludes that women sway more than men because they have larger, wider hips, their feet are farther apart, and their center of gravity is lower to the ground. In order for women to walk, women’s hips must move farther to the side over each foot. If Purvis’s theory is true, then women with slimmer hips should tend not to sway as much and these biological verities explain why.

But not only biology determines destiny. Some women we’ve talked to attribute their intermittent swaying to one piece of technology—the high-heeled shoe. The higher the heel, the more the pelvis is thrust forward. Most women will sway more when wearing high heels, if only to try to remain vertical.

But not all swaying is unintentional. Throughout the animal kingdom, males and females tend to attract each other by accentuating the features that most distinguish their sex. As wider hips are a female trait, then it would make evolutionary sense for women to accentuate these sexual markers to attract potential mates, just as males might wear tight T-shirts to emphasize their muscles (and too often, their beer bellies, as well). Sex symbols, from Mae West to Marilyn Monroe to Jennifer Lopez have sashayed in front of drooling suitors. Of course, women are not immune to the lures of hip-swaying. In exaggerated form, the early Elvis (“The Pelvis”) Presley outraged parents as he tantalized girls with his gyrations.

With the possible exception of dancers, no professional group is more associated with hip swaying than models. Willie Ninja, who works with models from OHM, IMG, and Metropolitan Modeling Agencies, specializes in developing models’ runway walks. He talked to us about the vagaries of his unusual coaching career.

Ninja reports that women vary widely in the amount of natural sway. Some of the variation can be attributed to anatomy (torso length and bone structure, for example), but he emphasizes the importance of personality and cultural forces. Some women with natural movement will suppress the sway, attempting to deflect attention, while others will shake their moneymakers to ensure notice. He notes that some cultures, such as Latin and African, encourage and expect women’s hips to sway noticeably, and models from these backgrounds generally do move their hips more. He has also noticed that women in rural areas tend to sway more than those in urban areas, the city dwellers presumably stifling their movements in order to deflect attention from aggressive males.

Ninja also believes that women’s hip movements have not been immune to greater cultural forces, such as the feminist movement of the 1960s. As it became less acceptable for women to use their “feminine wiles,” Ninja argues that women, at first consciously, and then later unconsciously, repressed the more blatant hip swaying of earlier times. Little girls then imitated their mothers, and the result is a generation of swayless women.

Nature has provided women with wider pelvic girdles than men, undoubtedly in order to facilitate childbirth. As in most cases of human dimorphism, the more prominent female attribute has been sexualized. In the sixteenth century, fashionable European women bought “hip cushions,” worn underneath their skirts to double the size of their hips, or at least the appearance of their hips. And while we now seem to favor a thin waist, surely part of the appeal of the thin waistline is its ability to accentuate the wider pelvis and breast.

Although most women disdain corsets and girdles nowadays, Victorian women took their breaths when they could get them—when in public, they were often tethered into restraints that, if worn by animals, would attract the attention of PETA today. During times when more androgynous looks for females were in vogue (the flapper era in the 1920s, the Twiggy era in the 1960s), not only did women wear looser, less shape-defining clothes, but actresses and models seemed to deemphasize hip gyrations. It’s hard to imagine Mae West slinking into a room wearing flappers, just as it would seem incongruous to see Twiggy, with her tomboy walk, wearing the kind of corseted outfits that Mae West or Pamela Anderson sport in their roles.

Even though women’s anatomies might naturally promote more hip sway, it’s hard not to believe that most swaying isn’t attributable to cultural, personal, and intentional forces.

Submitted by Rachel Rhee of West Bloomfield, Michigan.

UNIMPONDERABLES:

What Are Your Ten Most Frequently Asked Irritating Questions (FAIQ)?

Did you ever have a teacher who proclaimed that it is more important to ask good questions than provide good answers? We did. Unfortunately for us, he changed his position when we didn’t do so well on our

test

answers.

So we’ll understand it if you think us ungrateful wretches when we shout: Please, for our own sanity, please stop posing

faux

-Imponderables. After a hard day’s night answering reader questions, we wake up at the crack of noon, craving new Imponderables. But too often we are faced with what we coined (in

Why Do Dogs Have Wet Noses?

) “Unimponderables,” or “Frequently Asked Irritating Questions.” In

Dogs,

we did answer a bunch of the questions that we did not consider real Imponderables, in what turned out to be futile attempt to stanch the flow. In

Pirates,

we will try again.

It’s only fair for us to repeat the criteria we use to select the mysteries to answer in our books:

- 1.

They must present genuine mysteries, something the average person might have thought about but that most people would not know the answer to. - 2.

The mysteries should deal with everyday life rather than esoteric, philosophical, or metaphysical questions. - 3.

They are “why” questions rather than who/what/where/when trivia questions that could be “Googled” in a flash. - 4.

Seminormal people might be interested in the questions and answers. - 5.

They are mysteries that aren’t easy to find the answers to, especially from books. Therefore, they are questions that haven’t been frequently written about.

How much simpler our lives would be if we could simply outlaw standup comedy! In

Why Do Dogs Have Wet Noses?

, we railed against Steven Wright, George Carlin, and Gallagher, who all pose “Why” questions and run off the stage, bathed in applause and laughter, before they have to answer any of them. We forgot to add Andy Rooney, who on

60 Minutes

can stand our hair on edge when he starts a sentence with: “Ever wonder why…?” Before the Internet, at least the comedians’ Unimponderables were confined to their fans—but now the fans spread these irritating questions around by forwarding massive lists of them to innocent victims.

Can we stop this scourge? Probably not. But in the spirit of goodwill, fellowship, and irritability, we offer our brief answers to our most frequently asked Unimponderables.

1. Why Do Drive-Up ATMs Have Braille Markings?

About five years ago, this dislodged “Why Do We Park on Driveways and Drive on Parkways?” as our most frequently asked irritating question, which was fine with us—at least this old warhorse involves more than wordplay.

Yes, it’s true. If you look carefully at a drive-up ATM, you’ll notice the same Braille markings as on the ones inside. Why do banks bother? The simple answer is: They have to. The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, revised in 2002, mandates that “Instructions and all information for use shall be made accessible to and independently usable by persons with vision impairments.”

You might argue that any blind person who drives up to an ATM has more serious problems than vision impairment. But there are times when blind people do end up at drive-up ATMs. Obviously, the most common circumstance is when the blind person is driven by a friend, a relative, or a cab driver. Depending on the closeness of the relationship, the visually impaired person might not feel comfortable sharing a PIN number or the balance of an account with that other person. In some localities, especially on weekends in small towns, drive-up ATMs often become walk-up ATMs (not just by the visually impaired). The spirit of the ADA is that folks with disabilities, ranging from mobility to vision issues, should be able to accomplish as many tasks as possible independent of others.

We spoke to a group of Banc One executives in Denver, Colorado, who told us that they initially opposed this provision of the ADA in 1990, and were supported by their powerful trade group, the American Bankers Association. But when Banc One consulted with the ATM manufacturers, the executives realized that it would be more trouble than it was worth to use different configurations for ATMs anyway, and possibly more expensive.

Ironically, the Braille markings on walk-up and drive-up ATMs have come under fire from the visually impaired. Studies vary, but the consensus seems to be that approximately 15 percent of blind people are Braille-literate. Blind customers complain to banks when the ATM software changes, which necessitates learning a new set of keystrokes to complete the same transactions. As ATMs now allow customers to buy postage stamps, pay bills, look up their mortgage balance, and more, it increases the difficulty for blind people in performing even the simplest of transactions.

For these reasons, banks are being pressured to provide “talking ATMs,” ones that not only offer the customer a menu of choices for each transaction, but vocalize the contents of each receipt that is printed. But there are problems, too, beyond the obvious expense in programming and equipment. If the ATM speaks out loud, then passersby could hear intimate financial details (a thief might be more than casually interested in the dollar amount of a withdrawal). If a headphone system is used, who supplies the headphone? If it’s the responsibility of the bank, then how will the headphone be offered when the bank is closed? And must the bank supply headphones to drive-up ATMs?

Now you understand why Braille on drive-up ATMs might be an obsession to stand-up comics, but not the first concern of banks or the visually impaired.

2. Do Blind People Dream? If So, Do They Dream in Color?

They sure do dream, but most people who are blind at birth or become blind at an early age (up until the age of five or six) tend not to see anything in their dreams, although a small minority reports observing shadows or other abstract patterns. Most folks who were blinded at age seven or later experience visual images, sometimes just as vivid as fully sighted people, but often these images deteriorate over time. And yes, if they see images in dreams, they view them in color.

One of the best recent studies, “The Dreams of Blind Men and Women,” conducted by psychologist Craig S. Hurovitz and three colleagues (and available online at http://psych.ucsc.edu/dreams/Articles/hurovitz_ 1999a.html) corroborates these generalities but also finds that blind folks who can see limited or no visual imagery not only hear in their dreams, but often experience sensations of touch, smell, and taste. As far as we know, however, blind people do not dream about drive-up ATMs.

3. Why, Unlike Other Sports, Do Baseball Managers Wear the Same Uniform as the Players?

As anyone who has watched

The Office

will attest, management isn’t always all it’s cracked up to be. Nowadays, the onfield leaders of sports teams try to market themselves as combinations of the best attributes of Albert Einstein, Machiavelli, Julius Caesar, and Mother Teresa in order to justify their huge paychecks. But in the early days of baseball, the game managed to survive without a manager at all.

Before the twentieth century, teams had player-captains, but as the salaries in baseball increased, teams encouraged their aging stars to don the mantle of manager. Many of them spent years as player-managers, and wore the standard uniform for the most obvious of reasons—they still played the game. Player-managers and player-coaches were common well into the mid–twentieth century, but the tradition of managers wearing player uniforms has continued to this day, regardless of their physical shape (who could forget Tommy Lasorda waddling to the mound in his Dodgers uniform?). The last player-manager in the big leagues was none other than Pete Rose, the Cincinnati Reds’ troubled second baseman.

No law prohibits managers from wearing Armani if they wish, and a couple of Major League Baseball managers have bolted from tradition. Connie Mack, Hall of Fame leader of the old Philadelphia Athletics, who still owns the record for most wins by a manager, wore a suit to work. Burt Shotton, an ex-player who managed the Brooklyn Dodgers in the late 1940s, wore a team jacket over his suit and tie, a look that was unique, if unlikely to pass muster with the fashionistas.

We can’t think of any other sports where on-the-field management wears the same outfit as the players. We know of only one example where this tradition was violated even temporarily. In hockey’s 1928 Stanley Cup final game, Montréal Maroons player Nels Stewart fired a shot that hit New York Rangers goalie, Lorne Chabot, in the eye. Faced with no suitable replacement, 44-year-old Rangers coach Lester Patrick strapped on the goalie gear and played brilliantly—and the Rangers went on to win in overtime, 2–1.

4. How Many Licks Does It Take to Get To the Center of a Tootsie Pop?

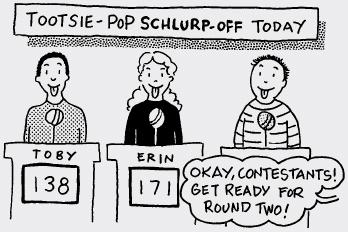

Although we get flooded with this question, its genesis is not from a standup comedian but from a 1970 television commercial that launched a long-lasting campaign. We classify this conundrum as an Unimponderable for what seems like an obvious reason: All licks are not created equal—there can never be one answer to this question because there is too much variation in the way Tootsie Pops are consumed. All lickers are not created equal, and neither are the Pops themselves. Does the number of licks increase when the Tootsie Roll center is, as is often the case, off-center? To the best of our knowledge, there are no empirical studies. And how can you calibrate your research to account for the irrefutable tendency of lickers to suck on the Pop?

All of these obstacles have not prevented the curious from conducting scientific experiments to determine the “lickiocity” of Tootsie Pops. In at least two bastions of higher education, Purdue University and the University of Michigan, students have concocted machines to simulate the licking mannerisms of humans, and they actually came to similar results (364 and 411, respectively). The Purdue students enticed twenty human volunteers and found that they averaged 252 licks per Pop.

Are there regional differences in Pop licking? Based on the data collected by the high school students at the Mississippi School for Math and Science, we’d have to assume so. Students attempted to test their hypothesis that boys would get to the Tootsie Roll center of the Pop faster than girls and quickly confirmed it: the mean for girls was a whopping 1,656 licks, versus 1,239 for boys. But the number was so much higher for these high school students than the college students. Is there a direct correlation between age and licking power? Higher education and consumption? Not clear! For it took junior high students at the Swarthmore School an average of a mere 144 licks to get to the center, demonstrating precocity, or perhaps, merely starvation.

Judging by our mailbag, it isn’t surprising that Tootsie Roll Industries claims that it has received tens of thousands of results from children, with an average of 600 to 800 licks. The discussion on its Web site indicates that Tootsie Roll has given up: “Based on the wide range of results from these scientific studies, it is clear that the world may never know how many licks it really takes to get to the Tootsie Roll center of a Tootsie Pop.” And we can live without an answer. After all, we agree with Mr. Turtle, who in commercials was asked how many licks it took him to get to the center. He replied: “I never made it without biting.”